Australian first- and second-year medical students’ perceptions of professionalism when (not) asking patients about Indigenous or Torres Strait Islander identification: A scenario-based experimental study

Original article (peer reviewed)Howard G A1, McArthur H M1, Platow M J1, Grace D M1, Van Rooy D1, Augustinos M2 (2019)

1 The Australian National University, 2 University of Adelaide

Corresponding author: Dr Michael Platow, ANU Research School of Psychology, The Australia National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, ph: (02) 6125 8457, email: michael.platow@anu.edu.au

Suggested citation: Howard G A, McArthur H M, Platow M J, Grace D M, Van Rooy D, Augustinos M (2019). Australian first- and second-year medical students’ perceptions of professionalism when (not) asking patients about Indigenous or Torres Strait Islander identification: A scenario-based experimental study Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 19(1) Retrieved [access date] from https://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/australian-first-and-second-year-medical-students-perceptions-of-professionalism

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by an Australian Research Council grant (Project ID: DP160101157). We would like to thank Dr Amanda Barnard, Gaye Doolan and Samia Goudie for their contributions to this work.

Abstract

Objective

Australian Best Practice Guidelines recommend that medical practitioners ask their patients a single standard Indigenous-status question. The present research investigated perceptions of this protocol by currently-enrolled Australian medical students.

Methods

Using a problem-based learning method, medical students were presented with a doctor-patient interaction in which: (1) the doctor’s Indigenous identity was implied (or not), and (2) an Indigenous identification request to the patient was made (or not). Perceptions of the professionalism of the encounter were measured using seven-point rating scales on 13 descriptive terms (e.g., professional, safe, appropriate).

Results

Ratings of the doctor’s professionalism were high across all conditions. However, the statistical interaction between the doctor’s own (implied) Indigenous identity and the request for the patient’s Indigenous identification was significant. Students considered it more professional for a non-Indigenous doctor to ask about patients’ Indigenous identification than to not ask; no such difference occurred when the doctor was Indigenous.

Conclusions

Students may see these best practice recommendations as only applicable to non-Indigenous doctors. However, the high ratings of professionalism overall suggest that while asking patients’ Indigenous identification was not seen as problematic, importantly, students did not recognise problems with not asking (counter to current best practice).

Implications

Pursuing these best practice guidelines should mean that not asking a patient’s Indigenous identification should be as obvious as not asking other fundamental questions about the patient. Despite textbooks highlighting cultural awareness, explicitly instructing students to follow this best practice will help establish it as normative practice for all medical professionals.

Download PDF version (429KB)

Introduction

Poor health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples1 are well documented, and have been the impetus for several government initiatives (e.g., Council of Australian Governments Closing the Gap initiative) aiming to equalise Indigenous and non-Indigenous health outcomes [1, 2]. In healthcare settings, explicitly asking patients about their Indigenous status enables practitioners to provide Indigenous-specific health services and interventions [1, 3, 4], such as health assessments [5], the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Closing the Gap co-payment [6], and the Department of Human Services Indigenous Health Practice Incentive Program [7]. In addition, the collection of Indigenous status information contributes to datasets that can be used to evaluate the success of these initiatives [8].

Alongside the policy and data implications of recording Indigenous status, qualitative evidence suggests that Indigenous people want to identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander in healthcare settings, provided the question is asked respectfully and that an explanation is provided as to why the information is being collected [9, 10]. The current national Best Practice Guidelines in Australia for collecting Indigenous status data recommend the following standard Indigenous status question be asked in all health settings: ‘Are you [is the person] of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin?’ [1]. This method of obtaining patients’ Indigenous status has been endorsed by the Royal College of General Practitioners [11] and is policy in three states and the Australian Capital Territory [e.g., 12].

Despite Indigenous peoples’ preference to identify, and Best Practice Guidelines endorsing the practice, under-identification occurs in both hospital and general practice settings [13]. An analysis by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found the proportion of ‘not stated’ responses ranges from 0.1 to 12 per cent across different health datasets [1]. In an examination of hospital admissions records across Australia, one study found that 22 per cent of records indicating Indigenous status were inaccurate [8]. Additionally, a cross-sectional study of General Practitioner (GP) training practices found that (1) patients had their (non-) Indigenous status documented only 53 per cent of the time, and (2) Indigenous patients, specifically, did not have their Indigenous status documented 20 per cent of the time [14]. Given that the vast majority of healthcare providers in Australia are non-Indigenous, they may not be aware of the importance of asking about Indigenous status in healthcare settings, or they may experience barriers to asking (e.g., attitudinal, educational, institutional) [13].

There are also processes specific to individual hospitals and general practices that impact on Indigenous status identification. These include providers being unsure how their practice identifies (or should identify) Indigenous status [5], or software not having adequate options for recording Indigenous status [3]. The attitudes and beliefs of healthcare providers also affect their willingness to ask about Indigenous status, with many of the perceived barriers demonstrating a lack of awareness and education [3]. Indeed, healthcare providers often believe Indigenous people do not wish, or are reluctant, to disclose their Indigenous status [1, 10]. Conversely, many healthcare professionals only ask patients who they believe ‘look Indigenous’ [4, 10], and/or patients are identified as Indigenous without being asked when doctors believe the patients look Indigenous [1, 4, 15].

One common theme emerges among studies of barriers to asking about Indigenous status: practitioners are reluctant to ask because they think patients will be offended [1, 4, 15]. One study found only 41 per cent of general practitioners or practice nurses disagreed that it is offensive to ask patients about their Indigenous status [15]. In other words, asking about patients’ Indigenous status was viewed as potentially offensive. In a similar vein, some staff report concerns about patients (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) becoming aggressive if asked [1, 10, 16].

Further explanations for not asking for Indigenous identification include failing to see the relevance of knowing the patient’s Indigenous status, believing that treatment should be the same regardless of background, and feeling awkward and uncertain about appropriate ways to ask the question [17]. Over a quarter of general practice registrars feel insecure about asking for identification [18]. These statistics highlight the importance of cultural training and education for current and future medical practitioners.

Although several studies have measured how healthcare practitioners view the issue of Indigenous identification, it is not known how it is perceived by medical students. This is despite Australian medical schools now including a compulsory Indigenous health component in their curriculum [19]. An analysis of an Indigenous health program at the University of Western Australia did find significant advancement in students’ knowledge, skills and attitudes, but it did not specifically assess attitudes about asking Indigenous identification in the clinical context [20]. In the current research, we examined precisely this issue, measuring first- and second-year Australian medical students’ perceptions of a clinical encounter in which an Indigenous or non-Indigenous doctor either asked or did not ask a patient about his (in this study, the patient was male) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification.

The exploratory nature of this research suggested a number of potential results. On the one hand, the primarily non-Indigenous students currently sampled may mistakenly believe it is inappropriate to ask about a patient’s Indigenous identification, although this may be less for second-year students who have had more education. On the other hand, students may correctly see not asking as inappropriate, again particularly among second-year students. At the same time, the implied Indigenous identification of the doctor may moderate these potential patterns. For example, Indigenous doctors may be given more leeway to ask or not ask. Hence, differences in students’ perceptions may only emerge with non-Indigenous doctors. In contrast, students may believe that asking patients about their Indigenous identification should come primarily, if not solely, from an Indigenous doctor. Notwithstanding these uncertainties, the current research will provide valuable insight into future Australian doctors’ perceptions of current best practice.

Method

Design and Participants

Ninety-three first-year and 81 second-year students enrolled in the Doctor of Medicine and Surgery, Medicinae ac Chirurgiae Doctoranda (MChD) at the Australian National University voluntarily participated in this study. The MChD includes an Indigenous health component across four years of study. Students received written statements of informed consent, and were informed verbally that choosing not to participate would have no negative academic impact. No payment or incentive was given. The median age of participants was 24 years (age range=20-45 years). Ninety students were female, 82 were male, and two indicated ‘other’ as their gender. One-hundred and twenty students were born in Australia, and 146 had English as their first language. Ninety-six participants were Caucasian, Australian, or of Western European ethnic background2 and 49 were of full or partial Asian ethnic background. Only two participants were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

Each student was randomly assigned to one condition of a 2 (doctor’s Indigenous identity: implied/not implied) x 2 (Indigenous identification request: made/not made) between participants design. The ethical aspects of this research were approved by the ANU Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol 2016/065).

Materials and Procedure

The experiment was administered during a lecture session via a paper-based questionnaire. The first page stated that the experiment was investigating students’ attitudes about a doctor-patient encounter and that students were to read a transcript between a medical doctor (‘Dr X’) and a patient (‘David’) who was seeing Dr X for the first time.

To manipulate the first independent variable, the questionnaire displayed an image of a business card ostensibly belonging to the doctor. The business card described Dr X as either a ‘Canberra-based doctor’ or as a ‘Ngunnawal representative to the Indigenous Medical Board of Australia’ (a fictitious medical board). The latter business card also contained an image of Indigenous artwork. All other elements of the two cards (qualifications and contact details) were identical. The ethnicity of the doctor (Indigenous implied or Indigenous not implied) was, therefore, not explicitly stated but was suggested through the doctor’s business card. We adopted this approach for two reasons: (1) to avoid demand characteristics and impression management behaviours by student participants that might occur if the doctor’s (non-) Indigeneity was made explicit, and (2) not to imply an Indigenous ethnicity through other methods as a means of respect (e.g., we did not suggest Indigenous ethnicity through the use of family names to avoid stereotyping). The implications of this implied procedure are considered below.

Students were then presented with a transcript of a supposed interaction between Dr X and David, with Dr X asking basic demographic questions of David (age, occupation and relationship status). To manipulate the second independent variable, Dr X ended the interaction either by asking David if he identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or if he were from Canberra.

Students were then asked to provide their impressions of the doctor-patient encounter by responding on seven-point Likert scales (1=‘strongly disagree’; 7=‘strongly agree’) to a series of descriptive terms. These terms were decided by four members of the research team, including the first two authors of this paper (who were, themselves, medical students). The descriptive terms were selected based on their face validity in capturing important aspects of doctor-patient encounters. Eight of the terms were worded positively (i.e., professional, a typical doctor-patient interaction, comforting, safe, appropriate, sensitive, good, fair) and five negatively (i.e., rude, abrupt, biased, inappropriate, prejudiced).

Finally, students answered a series of demographic questions and two experimental manipulation check questions. The first manipulation check asked students if they remembered whether the doctor was Indigenous or not (with options ‘Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander’, ‘not’ and ‘can’t remember’). The second asked students if the doctor had asked the patient if he identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (with options ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘can’t remember’).

Upon completion, students submitted their questionnaires into a ballot-type box (for anonymity) at the front of their classroom, were provided written debriefing sheets, and had all questions answered by one of the researchers.

Results

Three participants responded incorrectly to the Indigenous identification request manipulation check; removal of these three participants did not alter the pattern of results, so we maintained them in our analyses below. Unexpectedly, 61.40% incorrectly responded to the doctor’s Indigenous identity manipulation check. Participants’ written comments speak directly to this issue, with students noting, ‘I don’t think ethnicity of the doctor was ever specified’ and ‘Being a Ngunnawal rep doesn’t necessarily mean he is an Indigenous person.’ Of course, both of these comments are correct, and the reasoning behind our more subtle, implied approach to this manipulation was outlined in the Methods section. Despite the large number of ‘errors’ in the second manipulation check, our results (see below) suggest some impact of this manipulation on participants’ responses. Again, we retained all participants for analyses.

An exploratory principle components analysis with varimax rotation conducted on the 13 response items yielded three components with eigenvalues greater than 1. A scree plot, however, suggested a single component, confirmed by a parallel analysis [21]. Cronbach’s alpha for all 13 items indicated that a single component represented a reliable scale (α=.87). Hence, a mean of all items was calculated for each participant such that larger values represented more professional behaviour (i.e., negatively-worded items were reverse scored).

The overall grand mean on this professional behaviour scale was statistically significantly greater than the scale mid-point (i.e., indifference) of 4 (M=5.48, sd=.74; t(173)=26.48, p<.001). On average, the students at least somewhat agreed that the doctor-patient interview was professional. Seventy-three percent of students provided mean professionalism responses with values at or above 5 (somewhat agree). No student even somewhat disagreed the interview was professional; the lowest mean professionalism response was 3.32.

The professionalism scores were then analysed as a function of the independent variables. These responses, however, were significantly negatively skewed (z=-3.66, p<.05) which would violate analysis of variance (ANOVA) assumptions. A log transformation corrected this skew (z=1.51, p>.05; [22]), and these new values were used in a 2 (students’ year of study) x 2 (doctor’s Indigenous identity) x 2 (Indigenous identification request) between participants ANOVA. The interaction between doctor’s cultural identity and Indigenous identification request was the only statistically significant effect, F(1,166)=4.18, p<.05, ηp2=.03.

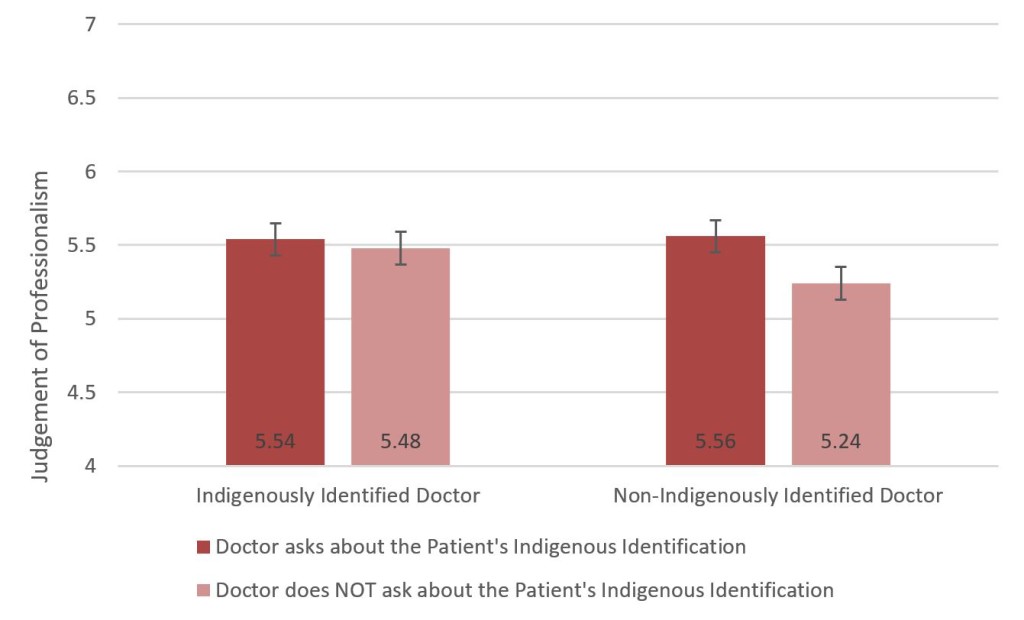

Simple main effect analyses [23] revealed no statistically significant difference in perceptions of professionalism when the Indigenous-identified doctor asked (or did not ask) the patient for his own Indigenous identification, F(1,166)=0.50. In contrast, students considered it more professional for a non-Indigenously identified doctor to ask about a patient’s Indigenous identification (than to not ask), F(1,166)=5.15, p<.05. This interaction is plotted in Figure 1, using the untransformed means for ease of interpretation (the identical pattern of significant and non-significant simple main effects also emerged with these untransformed data).

Figure 1. Medical students’ judgements of professionalism on untransformed scale as a function of the implied ethnic background of a doctor and whether or not the doctor asks if the patient identifies as Indigenous or Torres Strait Islander.

Note: The mean difference in judgements is statistically significant when there is no implication that the doctor is Indigenous. Numbers presented in the bars are mean values; vertical lines represent standard errors. Note that the original response scale varies from 1 to 7.

Discussion

The results of this study were straightforward and informative. Consistent with Best Practice Guidelines, the currently sampled medical students recognised the higher levels of professionalism exhibited in a doctor-patient encounter when the doctor asked – rather than not asked – about the patient’s Indigenous identification. There were, however, at least two qualifications to this pattern.

First, this difference did not emerge when the doctor was seen as Indigenous. Despite the large number of student participants erring in their ethnic identification of the doctor, students considered the encounter to be of relatively high professionalism regardless of what the doctor asked (or did not ask) the patient. This pattern of results suggests that students may see these best practice recommendations as recommendations for non-Indigenous doctors, with Indigenous doctors given the freedom not to ask.

A second, and more substantial qualification emerged when considering that the overall ratings of professionalism were high across all experimental conditions, but the magnitude of the effect size for the interaction was quite small. Simply put, the variability in responses is almost trivial when compared to the overall high ratings of professionalism. This broader finding is simultaneously encouraging and concerning. Encouragingly, these data suggest that the predominantly non-Indigenous medical students did not believe that asking a patient’s Indigenous identification was problematic. This is important in light of previous research that suggests doctors fail to ask this question in pursuit of a (potentially misguided) goal of non-discrimination. That is, they do not ask in order to treat all patients equally. Concerningly, however, these data also suggest that the medical students did not recognise any problems with not asking a patient’s Indigenous identification. The absence of pursuing these best practice guides did not raise alarm bells for these (even second-year) students.

Undoubtedly, identifying an absence is more difficult than identifying a presence [24]. Moreover, the current student participants may have expected that Indigenous identification was requested prior to the initial doctor-patient encounter. After all, although the students, on average, did not see the encounter as unprofessional, the mean rating was substantially lower than the most extreme point on the response scale (i.e., they perceived professionalism in the encounter, but also room for improvement). Nonetheless, if the Australian medical community is serious about best practice recommendations, endorsed by the Royal College of General Practitioners, then the absence of asking patients about their Indigenous identification in a clinical encounter should be as apparent as the absence of asking other fundamental questions (e.g., medical history). Current textbooks on clinical examination [e.g., 25] do, in fact, highlight the importance of cultural awareness, sensitivity and safety when working with Indigenous patients. We suggest that going one small step further, by explicitly instructing students to engage in best practice by directly asking patients about their Indigenous identification, would undoubtedly be a large step in establishing this best practice as normative and expected of any and all medical professionals in Australia.

Footnotes

1 In the present paper we use the terms ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’, ‘Indigenous’ and ‘Indigenous Australians’ interchangeably.

2 We recognise, of course, that the simple description as Australian does not necessarily imply being Caucasian or of Western European descent.

References

- AIHW: National best practice guidelines for collecting Indigenous status in health data sets, 2010. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468342 (accessed 30 Mar 2017).

- AIHW: The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 2015. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129550168 (accessed 1 Jun 2017).

- AIHW: Taking the next steps: identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status in general practice, 2013. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication- detail/?id=60129543899 (accessed 30 Mar 2017).

- Schutze H, Jackson Pulver L, Harris M. What factors contribute to the continued low rates of Indigenous status identification in urban general practice? A mixed-methods multiple site case study. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17(1): 95.

- Schutze H, Pulver LJ, Harris M. The uptake of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health assessments fails to improve in some areas. AFP 2016; 45(6): 415.

- PBS: The closing the gap – PBS co-payment measure, 2017. http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/publication/factsheets/closing-the-gap-pbs-co-payment- measure (accessed 1 Jun 2017).

- Australian Government Department of Human Services: Practice Incentives Program, 2017. https://www.humanservices.gov.au/health-professionals/services/medicare/practice- incentives-program (accessed 1 Jun 2017).

- AIHW: Indigenous identification in hospital separations data, 2013. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129543215 (accessed 30 Mar 2017).

- Scotney A, Guthrie JA, Lokuge K, Kelly PM. “Just ask!” Identifying as Indigenous in mainstream general practice settings: a consumer perspective. Med J Aust 2010; 192(10): 609.

- Riley I, Williams G, Shannon C. Needs analysis of Indigenous immunisation in Queensland – final report. University of Queensland Centre for Indigenous Health, 2004. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/data/UQ_121022/A2_Immunisation.pdf (accessed 30 Mar 2017).

- RACGP: Identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australian general practice, 2017. http://www.racgp.org.au/yourracgp/faculties/aboriginal/guides/identification/ (accessed 30 Mar 2017).

- ACT Health: Asking patients – “Are you of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin?”, 2016. http://www.health.act.gov.au/our-services/aboriginal-torres-strait-islander- health/policies (accessed 1 Jun 2017).

- Bywood PT, Katterl R, Lunnay BK. Disparities in primary health care utilisation: Who are the disadvantaged groups? How are they disadvantaged? What interventions work? Primary Health Care Research & Information Service, 2011. http://www.phcris.org.au/phplib/filedownload.php?file=/elib/lib/downloaded_files/pu blications/pdfs/phcris_pub_8358.pdf (accessed 1 Jun 2017).

- Thomson A, Morgan S, O’mara P, Tapley A, Henderson K, Van Driel M, Oldmeadow C, Ball J, Scott J, Spike N. The recording of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status in general practice clinical records: a cross-sectional study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016; 40(S1): 70-74.

- Kehoe H, Lovett RW. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health assessments: barriers to improving uptake. AFP 2008; 37(12): 1033.

- Lovett R. ACT public hospital staff attitudes concerning Indigenous origin information and estimating Indigenous under-identification in ACT public hospital admission data. Chapter 4. Australian National University: National Centre for Epidemiology and Public Health; 2006.

- Bywood P, Katterl R, Lunnay B. Disparities in primary health care utilisation: Who are the disadvantaged groups? How are they disadvantaged? What interventions work? PHCRIS Policy Issue Review. Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research & Information Service. 2011.

- Morgan S, Thomson A, Tapley A, O’Mara P, Henderson K, van Driel M, Scott J, Spike N, McArthur L, Magin P. Identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status by general practice registrars: Confidence and associations. Australian Family Physician. 2016; 45(9): 677.

- Phillips, G. CDAMS Indigenous health curriculum framework. Sydney, NSW: Committee of Deans of Australian Medical Schools. 2004.

- Paul D, Carr S, Milroy H. Making a difference: the early impact of an Aboriginal health undergraduate medical curriculum. Med J Aust 2006; 184(10): 522-525.

- Watkins MW Determining parallel analysis criteria. J of Modern Applied Stat Methods, 2006; 5: 344-346.

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson, 2007.

- Keppel G. Design and Analysis: A researcher’s handbook (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991.

- Treisman A, & Gormican S. Feature analysis in early vision: Evidence from search asymmetries. Psyc Rev 1988; 95: 15-48.

- Talley NJ, & O’Connor S. Clinical examination: A systematic guide to physical diagnosis. 7th ed. Sydney: Elsevier, 2014.