Review of methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

ReviewSnijder M1, Kershaw S1 (2019)

1 The University of Sydney, The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance use

Suggested citation

Snijder M, Kershaw S. (2019). Review of methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 19(3). Retreived from: https://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/review-of-methamphetamine

Contents

- Introduction

- Key facts

- Factors contributing to methamphetamine use in Australia

- Extent of methamphetamine use and misuse in Australia

- Health impacts of methamphetamine use

- Social impacts of methamphetamine use

- Responses to methamphetamine use

- Policies and strategies

- Concluding comments

- References

- Footnotes

Introduction

The most commonly used drugs in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are tobacco, cannabis and alcohol. However, methamphetamine use seems to be more prevalent among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders than non-Indigenous Australians. For example, the 2016 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were 2.2 times more likely to use meth/amphetamines than non-Indigenous people [1, 2].

Methamphetamine is a stimulant drug, which means that it increases the activity of the central nervous system and speeds up the chemical messages going between the brain and body. The use of methamphetamine and the related harms has been the subject of growing concern in Australia, with Australians rating it the drug of most concern in the 2016 NDSHS [2]. In general, the prevalence of methamphetamine use in Australia is relatively stable and has been for several years. However, there has been a shift towards using the more potent form, crystalline methamphetamine (or ‘ice’) rather than the less potent forms (speed and base) [3]. Crystal methamphetamine is considered to be widely available and accessible in Australia [4]. Crystal methamphetamine is often the purer form, which means that it gives a stronger and longer lasting high. However, it is also associated with more serious side effects along with long term mental and physical health effects including dependence [3].

Terminology

Data sources on methamphetamine and amphetamine use a variety of terms. These terms include [5]:

Amphetamines: a broad category that includes amphetamine, methamphetamine, dexamphetamine and amphetamine analogues. Some amphetamines are used for therapeutic purposes such as treating attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Methamphetamine: (also known as methylamphetamine) a derivative of amphetamine that is commonly found in three forms; speed, base, crystalline. It is structurally different, more potent and longer-lasting than amphetamine.

Meth/amphetamine: refers to methamphetamine and amphetamine and is a term often used in survey reports.

Amphetamine type stimulants (ATS): covers a large range of substances, which include amphetamine, methamphetamine and phenethylamines (e.g. ecstasy).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are experiencing a disproportionate burden of harm from amphetamines, including methamphetamine [6]. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who received support from Aboriginal primary health care services for substance use, amphetamines were the second most common illicit drug between 2015 and 2016 [7]. The number of Aboriginal primary health care services reporting amphetamines as a common substance-use issue increased from 70% of organisations in 2014–15 to 79% in 2015–16 [8].

About this review

The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of key information on the use of methamphetamines among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. The review provides general information on the context of methamphetamine use by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people including the historical, social and cultural contexts, and other social factors. It describes the extent of methamphetamine use in Australia, and the health and social impacts.

This review also describes programs and strategies that can reduce the harm related to methamphetamine use, in particular those that focus on prevention and education and the importance of localised responses and community support. Treatment options are also described, although few have been evaluated in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. The need for development of a workforce that is trained to address methamphetamine use in culturally appropriate manner is discussed, and the lack of policies and strategies that currently exist in this area is highlighted. The review concludes by discussing possible future directions for action and for minimising further harm.

This review draws mostly on journal publications, government reports, national data collections and national surveys, the majority of which can be accessed through the HealthInfoNet’s Library.

Edith Cowan University prefers to use the term ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ rather than ‘Indigenous Australian’ for its publications. However, when referencing information from other sources, our authors are ethically bound to utilise the terms from the original source unless they can obtain clarification from the report authors/copyright holders. As a result, readers may see these terms used interchangeably with the term ‘Indigenous’ in some instances. If they have any concerns they are advised to contact the HealthInfoNet for further information.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are extended to:

- the Matilda Centre research assistants, Katie Dean and Danielle Bradd, who assisted in collating the articles and reports used to inform this review

- the anonymous reviewer whose comments greatly assisted finalisation of this review

- staff at the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet for their assistance and support

- the Australian Government Department of Health for their ongoing support of the work of the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

Key facts

- Methamphetamine is considered to be widely available and accessible in Australia.

- In the 2016 National Drug Strategy Household Survey, methamphetamine was reported to be Australia’s number one drug of concern.

- While rates of methamphetamine use in Australia have been stable, the purity of methamphetamine used has increased, consequently increasing the harms associated with methamphetamine use. The use of methamphetamine affects not only the individual who uses the drug, but also families and communities.

- Use of, and harms associated with methamphetamine are more prevalent among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders than non-Indigenous people, with historical factors (colonisation and disempowerment) and social factors (housing, education and employment) being major influences.

- Families and communities have an important role in providing support to people who use methamphetamines and there is a need for resources and support for family and communities.

- Little evidence is available on effective approaches to prevent methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. However, there is some evidence available that diversionary activities and social marketing may be effective in preventing substance use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Research is currently underway to test effective responses.

- Cognitive behavioural therapy and contingency management have been found to be effective in short-term methamphetamine use reduction in mainstream populations and have been found to be appropriate for use with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients.

- Brief intervention and motivational interviewing have been shown to produce reductions in methamphetamine use as well as changes in client’s intention to use in mainstream samples. Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients, brief intervention and motivational interviewing have produced improvements in substance use and mental health outcomes in one study. More research is currently underway to further test the effectiveness of brief intervention and motivational interviewing amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients who are using methamphetamines.

- Supporting health workers and family members who are supporting people using methamphetamines is essential. The Family Well-Being Program is a response that has been found to be relevant for those supporting someone using methamphetamines. Further work is underway to develop programs for family members who are supporting loved ones who are using methamphetamines.

- Important elements of appropriate responses to methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are a strength based and holistic approach that is culturally appropriate and contains localised resources and services.

Factors contributing to methamphetamine use in Australia

There are many factors that influence the use of methamphetamine among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Historical, social, individual, family and community factors

Historical factors

Connection to Country[1] is important for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as it brings an identity, a sense of belonging and a place of nurturing; qualities that provide empowerment [10]. The European colonisation of Australia resulted in the loss of many traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lands, languages, cultures, law and customs. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were often displaced, mistreated and excluded socially and economically. This socioeconomic deprivation is linked to substance misuse among Aboriginal people, with the effects of colonisation and dispossession continuing to have an impact through intergenerational trauma [11]. Intergenerational trauma has also been perpetuated through successive government policies, notably the forced separation of children from their families [12].

In Australia, methamphetamine is considered to be widely available and accessible. It can be made domestically or imported from other countries. Historically, the increase in the supply and use of methamphetamine appears to have begun around the mid to late 1990s [13] in both the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, as well as non-Indigenous populations [14].

Social factors

Social determinants, such as education, employment and income influence health outcomes. Social determinants refer to ‘the close relationship between health outcomes and the living and working conditions that define the social environment… the higher the socioeconomic position, the better the health status on average’ p.142 [15]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on average have a lower level of education, lower levels of income and are more likely to be unemployed. Therefore, they are less likely to be in very good health and more likely to be associated with the use of illicit drugs including methamphetamine.

Education

The level of education an individual has affects employment opportunities, which in turn, affects an individual’s standard of living. Lower levels of education have also been linked to increased problematic substance use. Overall, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have lower levels of education, literacy and language compared with non-Indigenous people [16].

Employment

Unemployment can be a contributing factor for the misuse of alcohol and illicit drugs including methamphetamine. It can cause emotional distress and increase the likelihood of people taking illicit drugs to cope or manage problems. As reported in the 2017 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, 40% of unemployed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experienced high to very high levels of psychological distress, compared with 24% of those who were employed [17].

In general, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are less likely to be in full time employment than non-Indigenous people [18]; in 2016, 47% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (aged 15 to 64 years) were employed compared to 72% of non-Indigenous people [19].

Employment rates for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (15 to 24 years) also vary across the country. In 2016, the highest proportion of young people involved in education or work was in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) (72%), while the lowest rate was in the Northern Territory (NT) (39%) [18].

Income

The 2016 Census of Population and Housing detailed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, after adjustment for household size and composition, had a weekly household income of between $150 and $799 [18]. This is lower than non-Indigenous people who had an income between $400 and $1249. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in 2012-13 were less likely to be employed as professionals (13% of those employed) than non-Indigenous people (23%) and were less likely to be employed in the private sector (74% compared to 84% of non-Indigenous people) [17].

Financial insecurity can lead to people selling drugs, including methamphetamine, to provide an income. This increases access to the drug which can further impact families and communities as well as the individual [12].

Participants in the focus groups undertaken by MacLean et al. in 2017 [12] reported that Australian motorcycle gangs ‘bikies’ capitalise on Aboriginal people’s social disadvantage by aggressively marketing methamphetamine (particularly crystal methamphetamine) to them and encouraging them to commence dealing. Because of their close community connections, Aboriginal people were able to facilitate easy access to potential new users. Bikies and other dealers reportedly greeted people leaving jail with samples of crystal methamphetamine to ensure they maintained their dependence [12].

Access to health services

Inadequate access to health care services, particularly culturally appropriate services, can be a barrier for people who are affected by, or dependent on, methamphetamine and are seeking help. This is particularly true for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare ‘although three-quarters of the Indigenous population live in major cities and regional areas where mainstream health services are typically located, these services are not always accessible, for geographic, social and cultural reasons’ p.280 [15].

Additional barriers to health care include language, lack of education, culture, psychological, financial and time constraints. In the case of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, they often find it even more difficult to access mainstream primary health care services as they can often be faced with a number of additional barriers including experiences of discrimination and racism [20]. Intense shame has also been reported to prevent people who use crystal methamphetamine and their families from seeking help [12].

It is recognised that Aboriginal-specific health services are important providers of comprehensive primary health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait people [15]. There is an effort by the Australian government to provide fair and accessible healthcare for all, however, a challenge remains. Addressing the cultural barriers is a vital factor in addressing Aboriginal health inequality [21].

Individual, family and community factors

Individual

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have identified reasons for commencing methamphetamine use that are similar to those of non-Indigenous people [12, 22, 23]. These reasons include:

- to reduce inhibitions and increase confidence

- out of curiosity or to experiment

- to fit in or feel part of a social group

- to enhance pleasure

- to improve energy levels and enhance work performance

- to forget or cope with problems (e.g. unemployment, unstable housing, financial difficulties, lack of social support, stress, family break-up)

- to cope with relationship difficulties and death of loved ones

- to escape reality or out of boredom. It has been shown that a lack of social and recreational opportunities within regional communities has increased the appeal of methamphetamine use [23]

- to manage mental health issues (e.g. low mood, anxiety, depression) and the impacts of trauma. However, it is noted that mental health problems are also exacerbated by problematic drug use [24]

- to enhance sexual experiences and intimacy. For example, a study on young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people reported that 33% of males and 22% of females stated that they were ‘drunk’ or ‘high’ during their last sexual encounter [25].

The use of other drugs (e.g. alcohol, tobacco, cannabis) can also influence the likelihood of an individual trying methamphetamine. For example, one study found that of those who use methamphetamines, more than 80% of participants also drank alcohol three or more times per week [25]. Another study comparing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with non-Indigenous people in Queensland (Qld) found that in people who inject drugs, 20% reported dual dependence on methamphetamine and opioids [26]. This dual dependence was associated with psychological stress, however, in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander group it was also associated with social and structural factors (unemployment and incarceration). The study also reported that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were more likely to be methamphetamine dependent than opioid dependent and that recent trauma, shame and psychological stress were all associated with methamphetamine dependence [26].

Previous contact with the justice system and/or incarceration is an important risk factor [25]. Numerous studies have noted the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people within the adult and youth justice systems. In one Queensland study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who inject drugs, it was found that respondents with a history of youth detention or having been to prison reported an earlier age of onset for illicit drug use compared to those with no history of incarceration. The average age of first use for amphetamines was 17 years for those with a history of youth detention and 19 years of age for those who had been in prison only. Both of these were significant findings when compared with people who had no history of being in detention or incarcerated [27].

MacLean et al. report that shame can be a significant risk factor that intensifies an individual’s use of methamphetamine [12]. As the use of methamphetamine intensifies, the individual can become involved in crime or sex work to fund their habit, magnifying the shame. Also, it is not uncommon for people who use methamphetamine to hide it from doctors and other health care providers.

Family and peers

Family and peers can be either a protective factor or a risk factor for initiating and/or facilitating the use of methamphetamine. People who use methamphetamine often have friends, family or partners who use the same drugs and frequently spend time in places where these types of drugs are accessible and normalised (e.g. parties and nightclubs) [22].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are likely to have grown up in families suffering from the long-term effects of historical dispossession and punitive social policies and to have experienced trauma themselves though family conflict, substance use, racism and other problems. These experiences can make people susceptible to craving the positive sensations and feelings that are experienced when taking methamphetamine.

Community

Community can act as either a risk or protective factor for drug use. Having a strong connection to culture and country can be a protective factor for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [12]. However, dysfunctional community dynamics and limited support services can be a risk factor for drug use.

Unfortunately, methamphetamine is currently very accessible and relatively cheap in Australia [12]. In the 2018 Illicit Drug Reporting System interviews, participants commented that it was ‘very easy’ (64%) to obtain crystal methamphetamine which was a significantly greater proportion of respondents than in 2017 (56%; p=0.011) [28]. The report on the interviews also noted that although the median price of a point (0.1 gram) has remained stable at $50 since 2002, the median price of one gram was reported as $210 which is the lowest price since 2009. This ease of access can be a significant problem for communities especially if they have limited information, cultural leadership or resources to help manage problems associated with methamphetamine use. A recent study found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people were significantly more likely to use methamphetamine if it was easily accessible in their community [12].

Extent of methamphetamine use and misuse in Australia

Population statistics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2016, the Australian Bureau of Statistics [29] reported that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 3.3% of the total population of Australia, or 798,400 people. Of this total, 4% (32,200) of people identified as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, 5% (38,700) identified as Torres Strait Islander and 91% (727,500) identified as Aboriginal only [29].

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population are younger on average than the non-Indigenous population with a median age of 23 years, compared with 38 years [29]. Five per cent of the total youth population (aged 10 to 24 years) identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander [30].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely to live in regional, remote or very remote areas compared to non-Indigenous Australians, with 20% living in an outer regional area, 7% living in remote Australia and 12% living in very remote Australia [29].

Methamphetamine use by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

The 2016 NDSHS stated that 6.3% of Australians over the age of 14 years had reported ever using methamphetamines [2]. Similarly, the 2014-15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) reported that 5% of participants (aged 15 years and over) had used amphetamines, including methamphetamines, in the last 12 months. More males (6%) reported having used amphetamines than females (3%) [31]. The 2016 NDSHS also reported that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 14 years and over are 2.2 times more likely to use meth/amphetamine than non-Indigenous people [2]. This was an increase from the 1.5 times higher rate reported in the 2013 NDSHS, and the result was still present after adjusting for the difference in age structure [1].

A cross-sectional survey conducted with young (16 to 29 years) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at 40 community events, found that 9% of respondents (total number 2,877) had used methamphetamine in the past year [25]. Methamphetamine was the third most popular drug after cannabis (30%) and ecstasy (11%). Three per cent (3%) of participants reported ever injecting drugs, with methamphetamine the most commonly reported drug injected (37%) followed closely by heroin (36%). According to the 2013 Queensland Indigenous Injecting Drugs Survey (QuIDS) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were more likely to inject amphetamine type substances compared to non-Indigenous people (86% compared with 79%) [32].

Several studies report that there has been an overall increase in the use of methamphetamine among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Wilkes et al. [33] reported a 204% increase in the use of amphetamine-type stimulants by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people when data from 1993-1994 were compared with data from 2004. However, in non-Indigenous people there was only a 10% increase. A survey conducted in rural and remote areas of northern Queensland also found that ‘where meth/amphetamine is believed to be involved, workload and time commitment of front-line service providers had increased over the preceding six months compared with last year (2014)’ p.xiv [34].

A 2014 online survey designed to obtain information from front line workers who may come in contact with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people using amphetamine type stimulants (ATS), found that 79% of respondents stated that ATS use is a significant issue among their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients [35]. Ninety-two per cent (92%) stated that ATS use is a significant issue in their local community. Most respondents (88%) reported a recent increase in ATS use among their clients. Overall, the results suggest that levels and patterns of use differ by area.

Urban, regional and remote trends

A report looking specifically at trends in methamphetamine use between 2003-04 to 2012-13 identified that methamphetamine use in remote and very remote areas increased from 2.7% to 4.4% between 2004 and 2013 [36]. The 2016 NDSHS reported that people living in remote or very remote areas were 2.5 times more likely to use meth/amphetamines than those in non-remote areas [2].

In contrast, results from the 2014 GOANNA Survey [25] (the first Australian study of knowledge, risk practices and health service access for sexually transmissible infections (STIs) and blood borne viruses (BBVs) among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people), showed that meth/amphetamine use was highest among respondents from urban and regional areas (10% and 9%) compared to remote areas (6%).

Clough and Fitts [37] asked community members whether they thought ATS were being used in their rural and remote Indigenous communities. Of the 953 respondents, 6% specifically nominated crystal methamphetamine as being in their community with 11% nominating ATS as being prevalent.

Health impacts of methamphetamine use

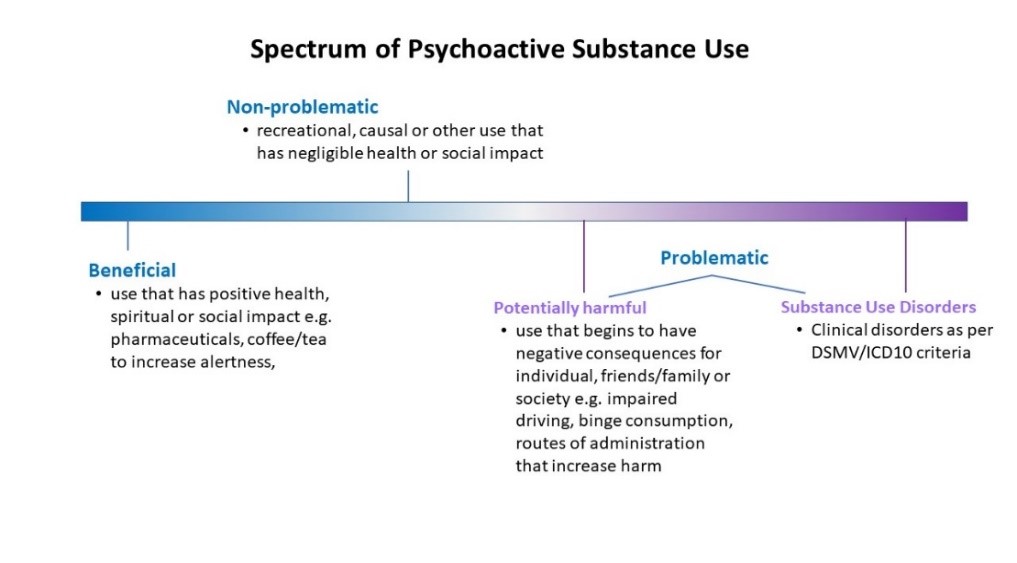

The effects caused by use of any substance can sit anywhere on a spectrum from beneficial to problematic use (including harmful use and substance dependence). Substance use may begin at one point on the spectrum and remain stable, or move gradually or rapidly to another point (see Figure 1) [38]. Some reports have found that most people who use crystal methamphetamines are recreational users and only a minority experience problematic use [39], including among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [40].

Figure 1. Spectrum of substance use from beneficial to problematic

Source: Reist D, Marlatt GA, Goldner EM, Parkes, GA, Fox J, Kang, S, Dive L, 2004 [38]

Methamphetamine use can affect people differently and may be more problematic for some people than others. The impacts of methamphetamine can also depend on how much is consumed, the purity of the substance, the route of administration, the person’s tolerance, as well as their physical and mental health. Small amounts or mild intoxication of methamphetamine is associated with initial feelings of euphoria (intense excitement or happiness, also called a ‘high’) wellbeing, confidence and increased alertness due to the release of dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin in the brain. However, as the drug wears off a person may feel depressed, exhausted and irritable [41]. Heavy and repeated use is associated with more serious side effects. The use of crystal methamphetamine (the purer form) has also been shown to produce a stronger and longer lasting ‘high’, however, it is also associated with more adverse effects [3].

Overall, effects and impacts of methamphetamine use can include [42]:

- physical effects:

- increased blood pressure

- increased temperature

- increased energy

- increased attention, alertness and talkativeness

- headaches and dizziness

- dehydration

- nausea, vomiting, weight loss

- seizures

- jaw clenching and dental problems

- risks of blood-borne viruses from injecting

- psychological and social harms:

- depression

- feelings of anxiety and paranoia

- increased feelings of anger

- aggression and violence

Major harms associated with methamphetamine use include increased risk of stroke (and other cardiovascular problems), dependence, psychosis, aggression, violence, overdose and death [43-45]. Recently, there has been an increase in rates of physical, psychological and social methamphetamine-related harms in Australia generally [1, 2]. This is evidenced by an increase in methamphetamine-related helpline calls, drug and alcohol treatment episodes and hospital admissions [43, 44]. Increases in harms most likely reflect increases in regular and dependent use, as well as a shift to the crystal form. Although there has been an increase in regular and dependent methamphetamine use, it is important to note that not everyone who uses methamphetamine will become dependent [20].

It is important to recognise that the effects of methamphetamine not only impact those who use methamphetamine but also their families, friends, communities and workplaces [46]. It should also be noted that methamphetamine may be mixed with other drugs (e.g. ketamine) or substances (e.g. glucose) prior to being sold, and these impurities can potentially cause other adverse effects [47]. ‘You don’t always know what you’re getting’ was one of the risks reported by Aboriginal people who use methamphetamine, during in-depth interviews in 2008 p.92 [23].

Mental health and hospital admissions

People who use methamphetamine may experience mental health problems while using the drug, with symptoms lasting from a few days to a few weeks [48]. Hospital records show that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are relatively high users of public hospital services, with mental and behavioural disorders being listed as one of the main causes of hospitalisation [17]. Given the strong link between mental health and substance use, and also the mental health effects of methamphetamine it is likely that some of these cases may be due to drug use [1].

This is supported by national data which suggest that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to present for treatment following amphetamine use [49, 50]. From 1986-1990 to 1991-1995 first time hospital admissions in relation to amphetamine use in Western Australia (WA) increased 18-fold in the Aboriginal population compared to 10-fold in the non-Aboriginal population [14]. More recently, Monahan [6] found two thirds (66%) of ATS related emergency department presentations in the Pilbara region of WA were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, despite representing just 16% of the Pilbara population. Psychotic disorder was the most common reason for admission, along with other mental and behavioural problems. Males made up 76% of hospital admissions and 53% of these identified as Aboriginal (99 hospital admissions) [6]. Queensland Health has also noted an increase in methamphetamine-related hospital admissions in Qld for Indigenous people, from 18 in 2009-10 to 443 in 2015-16 (see Table 1) [51].

Table 1. Number of methamphetamine-related hospital admissions by Indigenous status, Qld, 2009-10 to 2015-16

| Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total |

| 2009-10 | 14 | 4 | 18 | 82 | 33 | 115 |

| 2010-11 | 16 | 8 | 24 | 160 | 86 | 246 |

| 2011-12 | 24 | 9 | 33 | 288 | 132 | 420 |

| 2012-13 | 25 | 14 | 39 | 431 | 211 | 642 |

| 2013-14 | 78 | 49 | 127 | 753 | 353 | 1,106 |

| 2014-15 | 134 | 72 | 206 | 1,130 | 632 | 1,762 |

| 2015-16 | 261 | 182 | 443 | 1,633 | 941 | 2,574 |

Source: Queensland Health, 2017 [51].

In South Australia (SA), there was an eight-fold increase in hospitalisations among Aboriginal patients for stimulants (including methamphetamine), from 20 in 2007-08 to 162 in 2015-16. The rate per 10,000 Aboriginal population has also increased seven-fold, from 6.9 in 2007-08 to 47.2 in 2015-16 [52]. In Victoria (Vic), a residential Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service also found that the number of clients reporting amphetamines as their primary drug of concern significantly increased from approximately 12 (± 2.78) people in 2015 to 21 (± 7.19) people in 2016 [53].

Mortality

In general, there has been a rapid increase in the number of deaths involving methamphetamine in Australia. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported that the death rate in 2016 was four times higher than in 1999 [5]. A review of the Australian National Coronial Information System (NCIS) found that between 2009 and 2015 there were 1,649 cases where methamphetamine had been recorded as contributing to death. Deaths were due to accidental drug toxicity (43%), natural disease (e.g. coronary heart disease, stroke) (22%), suicide (18%), other accident (e.g. motor vehicle accidents) (15%) and homicide (1.5%) [44].

However, there is limited recent data available on the proportions of methamphetamine-related deaths in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

One older study in 2000, examining suicide among Western Australians aged 15-24 years during 1986-1998, reported that stimulants (including methamphetamine) were detected in 9% of male and 8% of female deaths [54]. Further investigation into the rate and impact of methamphetamine-related deaths in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across Australia is needed.

Injecting drug use

One of the most common routes of administration for methamphetamine is by injection [23]. There are several health harms associated with injecting methamphetamines, including increased risk of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and other blood borne viruses (BBV).

A few studies have found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to start injecting at an early age, report needle and equipment sharing, inject more frequently and to be positive for HCV [55-57]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who inject drugs have indicated that feelings of shame prevent them from accessing needle and syringe programs.

The GOANNA study reported that 3% of Indigenous young people (16 to 29 years) nationally had injected any drug in the last year [25]. Methamphetamine was the most frequently injected drug (37%) followed closely by heroin (36%). The incidence of needle sharing in this population was reported to be 37%, with 45% reporting sharing other injecting equipment (spoons, filters, swabs). Men more frequently reported injecting compared to women (62% compared to 39%) while heterosexual participants were less likely to report injecting (71% compared to 93%). Methamphetamine was the most common drug injected in regional areas with heroin the most common drug injected in urban areas [25, 58].

Sexually transmitted infections

The use of illicit drugs increases the risk of STIs [59]. STIs are a diverse group of infections that all share a common route of transmission – sexual contact. STIs include chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis, and the viral infections HCV, HIV, and Hepatitis B virus (HBV) [60].

A risk factor for contracting an STI is having multiple sexual partners. In a study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, those who used methamphetamine were more likely to report a higher number of sexual partners in the past 12 months and more likely to be associated with a previous STI diagnosis [25].

In a study by Ward et al. it was reported that while the rate of newly diagnosed HIV appears to be similar between Aboriginal and non-Indigenous people, the demographic patterns of infection are very different with a higher proportion of HIV cases in Aboriginal people attributed to heterosexual contact, occurring in women, or associated with injecting drug use (such as methamphetamine) [25].

Social impacts of methamphetamine use

Methamphetamine can cause or contribute to a wide range of social impacts among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population.

Violence and aggression

Violence and aggression associated with methamphetamine use can impact on families (including children), communities and front-line workers. Although the relationship between methamphetamine (particularly crystal methamphetamine) use and aggression is not straight forward, use of the drug can increase aggression in some people, with men being the most likely to be affected [51]. Feelings of irritability, paranoia and mood swings are also common and can make individuals more likely to exhibit violent behaviours especially if they use methamphetamine heavily. One study found that people who use methamphetamine chronically are six times more likely to behave violently when using methamphetamine than when they have not consumed the drug. The likelihood of violent behaviour was shown to increase when people used the drug more frequently, experienced psychotic symptoms, or had heavy alcohol consumption [45].

A study by Clough and colleagues [34] found that front line service providers in Qld observed that people who use meth/amphetamine tended to:

- be agitated or violent requiring physical restraint or police intervention

- be threatening self-harm or suicide

- appear paranoid, delusional, experiencing bizarre thinking or hallucinations

- be unusually suspicious of others around them

- be agitated or violent requiring sedation.

Children, families and communities

There is evidence that methamphetamine use in pregnant women can have an adverse effect on both the mother and foetal development. The use of methamphetamine has been linked with bleeding of the placenta, miscarriage, early labour and an increased risk of foetal abnormalities [51]. Babies can be born premature, with a low birth weight and exhibit signs of withdrawal such as excessive crying and irritability [61]. They are also more likely to feed poorly, cry excessively, be sleepy or irritable and be admitted to the special care unit in the hospital [61, 62].

Children with parents who use drugs, including methamphetamine, are at risk of interrupted emotional and physical development. This can occur because of chaotic and unstable household environments which can lead to a children’s physical, emotional and developmental needs being unmet, and/or an increase in abuse or neglect [63]. Children who suffer from abuse or neglect are more likely to go into welfare or informal care arrangements [64].

Excessive drug use not only impacts on those taking the drug, but also takes a heavy toll on their families and can increase tension within the family [65]. The Inquiry into the Supply and Use of Methamphetamines, particularly ice, in Victoria highlighted the damaging effect of methamphetamines on families. It outlined stories of ‘financial strain and loss of assets, families providing round‐the‐clock support to loved ones who are agitated and awake during periods of intoxication, and fear of aggression and violence’ p.674 [66].

In 2008, stakeholder interviews of workers in Drug and Alcohol Units in Aboriginal Medical Services and Mental Health Services in New South Wales (NSW), SA and WA were conducted. One of the findings from these interviews was that authorised interventions are traumatic and that often the family feel very guilty about contacting authorities. This research also found that families and communities find it difficult to cope with methamphetamine use due to the aggressive behaviour associated with use. This is can also lead to greater concern about safety in communities and households [23].

A Victorian study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who inject drugs found that ‘the biggest concern with the clients interviewed for the project was their family’s negative reaction towards their injecting drug use behaviour’ p.21 [67]. In particular, clients cited fears of shaming and stigma from their family and community, as well as the potential for physical violence if the family learned of their habit. These fears directly affected how they accessed injecting equipment, with many clients unwilling to collect clean injecting equipment from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Services where they may be identified by members of their community, preferring instead to use mainstream services that were more anonymous.

However, family ties can be a strong positive motivator for people to seek help for their methamphetamine use. It was noted that family reintegration provided the strongest motivation for change for Aboriginal people who used ice [12]. Involving families in the treatment process is important as it has been shown that family relationships may encourage compliance with treatment and be a protective factor against relapse [68].

Communities can also be negatively impacted by an individual’s use of ice. For example, the violence and aggression, which is associated with methamphetamine use, can impact front line staff such as police, paramedics and hospital staff [64]. The perception of safety within the community can also be affected, leading to people feeling lost, helpless and scared. Disconnection from family and community may intensify isolation and despair [12], therefore it is important to equip communities to better understand methamphetamine and how to manage issues related to its use.

Crime and incarceration

The association between the use of illicit drugs and crime is complex and unclear as not all people who use drugs commit crimes, and of those who do, some use drugs prior to offending while others are offenders prior to using illicit drugs [69]. It should be noted that also, in general, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience much higher rates of contact with the criminal justice system and are almost 14 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous people [70].

There have been a few reports that indicate the relationship between methamphetamine and crime, however, there is limited information specific to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population.

In general, people who use methamphetamine have reported deriving a significantly higher proportion of their income from crime (e.g. property offences or drug-related crime such as intoxication) compared to people who do not use drugs [69]. They have also stated that their use of methamphetamine played a contributing role in their offending, most commonly through intoxication or the need for money to purchase drugs.

An Australian study of police detainees found a higher rate of property offences was recorded for people who use amphetamine heavily at the time of arrest, compared with non-users and moderate users [71]. It was noted that employment status, gender, age and Indigenous status were significantly associated with rates of property offending.

In a study of 1,146 police detainees in Australia in 2013, 36% of detainees reported using methamphetamine in the 30 days prior to their detention. This study also found that in detention, a higher proportion of people who use methamphetamine were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander [69].

Responses to methamphetamine use

There is currently little evidence available on effective responses to specifically addressing methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [72]. This section of the review will therefore draw together best practice examples of programs addressing methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and combine this with evidence for effective approaches among mainstream populations, overseas Indigenous peoples and evidence from other illicit drug approaches with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. There have been various studies that investigate needs and preferences among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to respond to methamphetamine use that can provide reasonably clear directions for the development of appropriate strategies. These include:

- Family support: The importance of family for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is highlighted in the literature on methamphetamine use, including the preferential involvement of family in treatment, and for supporting family members of people who use methamphetamine [12, 34, 72-75]. Most current services provide support to the drug-using individual only, and in residential rehabilitation the client is taken away from the family. The literature identifies that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people would prefer rehabilitation services where their family can come with them. It can take a lot of effort to support someone who is dependent on methamphetamines and family support programs have been identified as a need. Support programs are currently being developed by researchers at the University of Newcastle (Box 1).

- Culturally appropriate/safe: As described throughout this review, ensuring the cultural appropriateness of prevention and treatment services is essential in addressing methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This includes a focus on addressing the right social determinants, and acknowledging the importance of connection to country, community and family, cultural strengths and the history of colonisation and disempowerment. The latter requires prevention and treatment to focus on healing of past and current traumas. Examples of appropriate services are healing centres (see section Healing centres). Services need to provide their staff with anti-discrimination training and advice on how to talk effectively with their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients who may be using methamphetamines. This is especially needed in primary health care services that form the first level of access to care.

- Holistic services: As described above, methamphetamine use and dependence do not occur in isolation and is often associated with other issues associated with social determinants. The literature highlights the need for holistic services that go beyond providing help for the methamphetamine issue, but also provide support in other areas of the clients’ lives. For example, Youth Empowered Towards Independence (YETI) based in Cairns Qld, provides drug and alcohol counselling to young people aged 12 to 25 years as well as case management around housing, support with employment and finances and family support. Another example is the Bumps to Babes and Beyond program delivered by Mallee District Aboriginal Service (MDAS), Vic. This program provides high-risk families with holistic support from housing to family services and child protection, with the aim to keep the children living with their parents [66].

- Strength-based approach: According to the literature, rather than focusing on issues and struggles in communities, there is a preference for an approach that focuses on the strengths of individuals and communities and how they can address issues around methamphetamine use [37, 76]. This includes sharing positive messages from individuals and communities who have successfully addressed their methamphetamine issues.

- Localised resources and services: There is a need for more detox and residential rehabilitation facilities in regional and remote areas so that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (and other people who use drugs) can stay close to family and close to their traditional lands. More localised services also mean that the treatment can be better adapted to the local community’s culture. In addition, the localisation of social marketing, information and education messaging makes them directly relevant for the target group.

Box 1. New and emerging programs: Family and Friends Support Program (FFSP)

Family and Friends Support Program (FFSP) is an evidenced informed online intervention and support package for families and friends supporting loved ones using ice. It includes information on how families and friends can best help their loved ones and protect them from adverse impacts of their drug-using lifestyle. FFSP recognises that supporting someone who is using drugs can be extremely stressful, and aims to assist families and friends to best manage the demands of this role. The online program was developed by researchers and clinicians at the University of Newcastle in conjunction with the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales. Expert guidance was also provided by researchers and clinicians from the University of Bath, United Kingdom and the Addiction and the Family International Network (AFINET). Funding for this program was provided by the Australian Department of Health. FFSP is publicly available on www.ffsp.com.au. An expansion of FFSP is now underway to: improve access to evidenced based information about alcohol and other drugs for affected family members and friends; provide information about how to access services and/or support for a loved one using alcohol and/or other drugs; and provide an online support program. The expansion will be conducted by researchers from the University of Newcastle and the University of Sydney.

Prevention and education

As with other types of drugs, prevention of methamphetamine use and related harms is important. This has been highlighted by several authors over many years [23, 34, 66, 73]. With reports of some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth starting drug use (including methamphetamine use) as young as 11 years old, some researchers have advocated for drug education to start in primary school [34]. While school-based drug prevention has been identified to be effective in delaying uptake of alcohol and cannabis in mainstream populations [77], there are currently no school-based drug prevention programs that have been shown to be effective for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students [78], or for methamphetamine use specifically [72]. The general consensus is that effective drug prevention programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth should go beyond providing information and focus on developing interpersonal skills, resisting peer pressure and integrating cultural knowledge elements and should be developed with the local community [34, 73, 78].

Diversionary activities

Diversionary activities have been identified as strategies to prevent drug and alcohol use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in general [78, 79], and methamphetamine more specifically [66, 80]. Examples of diversionary activities include drug and alcohol-free festivals and events, and sporting and cultural activities in the community. The rationale behind providing diversionary activities in the community is to alleviate boredom (that can lead to substance use [81]), create support networks in the community, and provide young people with ways to build confidence and self-esteem. It is, however, important to note that diversionary activities are likely to be most effective in preventing substance use, including methamphetamine use, when they are provided in conjunction with other activities, such as educational opportunities, drug and alcohol education and empowerment opportunities for the participants [82].

Social marketing

Social marketing and mass media campaigns have been identified in qualitative studies as having the potential to educate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people about methamphetamine and how it can affect the individual, their family and the community. They can also help family members identify when their loved one is consuming methamphetamine and provide guidance for how to find support [12, 23, 72]. Several studies have identified that there is a need for more information about methamphetamine for community members and family members [34, 37, 66]. As a response to this need for education, the Australian Department of Health has funded the development of an online, evidence based information and education toolkit about crystal methamphetamine for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (see Box 2). Other studies have identified that it is important to not stigmatise or shame people who use methamphetamine [12]. Campaigns should not be dehumanising and they should provide suggestions for ways that people who use methamphetamine can be helped to overcome harmful use [12]. This is primarily because stigma and shame around use have been identified to be significant barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to seek help for their use [26]. A positive example from American Indian communities was a reduction in methamphetamine related arrests and incidents that was attributed to a social marketing campaign that focused on strengthening culture and looking for help [83].

Various Australian organisations have developed campaigns and short videos to highlight positive stories and give people who use methamphetamines and their families a sense of optimism that change is possible and how families can support their loved ones to change. Examples of these include: New South Wales police Not Our Way campaign [84]; Mallee District Aboriginal Services (MDAS) Healing from ice use in Victorian Aboriginal communities [85].

Box 2. New and emerging programs: Cracks in the Ice Toolkit for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

The Australian Department of Health has funded The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use at the University of Sydney, to adapt the Cracks in the Ice online community Toolkit (www.cracksintheice.org.au) to be culturally appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. They are also developing additional culturally appropriate resources. At the time of writing this review, in collaboration with the National Drug Research Institute, consultations around the country have been completed with people with lived experience, community members and health services to investigate needs and preferences for the online toolkit [75]. Based on these consultations a roadmap for development of the toolkit has been prepared that will guide the development of the online toolkit over the coming years.

Community-based responses

While the above approaches are likely to assist in addressing methamphetamine use and associated harms in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, it is important to acknowledge that a one-size-fits-all approach will not work and that solutions need to be community specific [76, 86]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have called for localised approaches to prevention of methamphetamine use and related harms. Such localised responses need to be based on effective actions and existing community-strengths where possible. While there is currently a lack of evaluations of effective community action against methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, it is helpful to look at strategies that appear to work in other communities. Various qualitative studies have identified a need among community members, and family members of people who use ice to promote positive examples of how individuals and communities have address methamphetamine use and related harms in their own lives and communities. Community strengths can be identified through community forums and the establishment of community coalitions. Community forums focussing on methamphetamine (or ‘ice’ more specifically) have been successfully organised by police, government and non-governmental organisations around the country and have formed a place for community members to discuss their worries, share experiences, learn about methamphetamines (and ‘ice’) and to develop community-based responses [80, 87, 88].

Documented positive examples of communities initiating their own response against methamphetamine use in their community highlight the variation in responses. One example that is frequently quoted is an Aboriginal community in Redfern essentially banning the use of methamphetamine on The Block (a social housing block owned by the Aboriginal Housing Company in Redfern, NSW). In addition, community members would portray overtly negative behaviours towards people known to use ‘ice’ (e.g. by growling at them). For many community members this was more of a deterrent against methamphetamine use than any official policing on The Block [23, 72].

Another positive community-based response to prevent methamphetamine use is Project Ice Mildura [72]. In this intervention, community-based mainstream organisations, the police, Aboriginal Health Services, the City Council and community members are working together to raise awareness around issues surrounding methamphetamine use in their community and taking action around issues. An evaluation of the project showed positive results in relation to increased awareness by community members and increased reporting to the authorities around methamphetamine related issues [89]. The project has also created momentum in the community to increase efforts, including advocating for more appropriate withdrawal and rehabilitation services for people who use methamphetamine. The outcomes of this project were a community report and making a short video for community members (see discussion in social marketing paragraph above).

Another approach was that used by the Indian Country Methamphetamine Initiative (ICMI) in the United States of America (USA) where 15 Indian communities worked together to establish responses to address and prevent methamphetamine use in their communities [83]. Each community established coalitions consisting of stakeholders from their communities. Each community implemented responses based on their priorities and included things like: working together with law enforcement, individual/family treatment approaches, community mobilisation (through community forums and activities), public information and awareness raising (social marketing) and focusing on reviving culture. While ICMI has not been evaluated for its effectiveness in reducing methamphetamine use, the evaluation showed that it improved the communities’ capability to implement activities against methamphetamine. Given that the community environment can strongly influence why someone is using methamphetamine, such community development initiatives can be preventive. However, research is still needed to identify its effectiveness in reducing methamphetamine use and related harms.

At the time of writing this review, work is underway in Australia to evaluate the effectiveness of the Communities that Care approach in reducing methamphetamine use and harms in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (see Box 3) [90]. In response to the recommendations made in the Final report of the Ice Task Force in 2015 [91], the Australian Government, through the Australian Drug Foundation has funded 172 communities (including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities) to undertake action against drug and alcohol use and related harms in their community (local drug action teams) [92].

Box 3. New and emerging programs: the Novel

Interventions to Address Methamphetamine Use in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities (NIMAC) studyAssociate Professor James Ward and a team of researchers at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI) are undertaking a project funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). The aim is to develop new approaches to address methamphetamine use and related harms in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Phase 3 of this project involves working with 10 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to implement the Communities that Care (CTC) approach. This approach has been proven to prevent and reduce substance use and related harms in the USA as well as in mainstream Australia. The participating communities will form coalitions and implement interventions to address methamphetamine use in their own community. Associate Professor Ward and his team will evaluate the effectiveness of the CTC approach in addressing methamphetamine use in these communities. For more information see: nimac.org.au [90].

Addressing the social determinants

An important component of preventing substance use, including methamphetamine use, is to address the social determinants that influence methamphetamine use. As identified in this review (see section Factors contributing to methamphetamine use in Australia), lack of education and unemployment are among the strongest contributors to methamphetamine use. As with previous programs discussed, not many formal evaluations of the impact of methamphetamine use exist, however, several studies and inquiries have identified that positive education and employment programs that address these underlying social determinants have the potential to prevent methamphetamine use [66, 73, 80, 87, 93, 94].

Education and employment

One program that has been identified as having a positive effect was the Pathways program coordinated by Winnunga Nimmityjah Aboriginal Medical Service in partnership with Community Education and Training in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) [73]. In this program Aboriginal people are supported to obtain their driver’s licence. The program gave financial assistance to participants to pay for outstanding traffic fines, drivers’ lessons and theoretical exams. Qualitative interviews indicated that among people who use methamphetamine identified this as a positive program and that people who had participated in the program started looking for work as well as undertaking further training and education. While it did not measure reduction in drug use, increase in training and education likely contributed to less drug use.

In 2014 the Parliament of Victoria’s Law Reform Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee conducted an inquiry into the supply and use of methamphetamines in Victoria [66, 87]. One of the objectives was to identify programs that were focusing on improving educational and employment outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, with the aim to prevent methamphetamine use. These programs target people from kindergarten through to university. It is important to note that none of these programs have been evaluated for their effectiveness in preventing methamphetamine use, or substance use more generally, however these programs have been shown to be successful (to varying degrees) in engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in education and employment.

One of the most promising programs to improving wellbeing by addressing the underlying social determinant of education is the Clontarf Academy. The Clontarf Academy for Aboriginal boys commenced in Western Australia (WA) in 2000 and has now been rolled out across the country [93, 94]. In 2017, nearly 6,000 Aboriginal young men were participating in a local Clontarf Academy. The program uses Australian Rules Football to engage the young men in education and support them to complete their Year 12. While the aim of the program is not to improve the football skills or create footballers, it uses football to attract young men into the program, improve their self-esteem, develop skills, change behaviour and experience success, and reward achievements. The boys in the program have a school attendance rate of 80% compared to an average attendance rate of 69%-81% for Indigenous Year 10 students overall. Eighty per cent (80%) of the young men in the program finish Year 12, compared to a 45% retention rate for Indigenous students nationally.

Housing

Another social determinant that is a risk factor for substance use, including methamphetamine use, is housing. One innovative way to improve housing conditions and reduce the risk of substance use, including methamphetamine use was the introduction of a scheme by the Woorabinda Council, Qld, to reward renters when they paid their rent on time [80]. Rental arrears were a big problem in this area, which meant there was not enough money to repair housing, and the condition of the houses was deteriorating. The reward for those who paid their rent on time was to be entered into a prize draw where they could win items such as fridges and washing machines (they would hand their currently working appliances down to friends and family who were in need of these items). The success of the scheme led to people paying their rent on time, there was money to conduct repairs and people’s standard of living increased by having better appliances due to winning the prize draw.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction approaches are important in responding to methamphetamine use in order to reduce harms from use. Some users might be unlikely to stop their use, but implementation harm reduction strategies will allow them to experience less harm from their use. Recommended harm reduction practices for people who use methamphetamines include: [95-97]:

- avoiding multiple substance use simultaneously with methamphetamine use, including coffee and alcohol, as this can lead to unpredictable effects on the body.

- being aware of safe injecting practices. Injecting remains the primary way methamphetamines are administered, despite the well-known risks associated with this method. Safe injecting practices include using new needles, not sharing needles, disposing of used needles and where possible inject in a safe injecting space.

- staying hydrated and taking time out to rest if needed. The impact of methamphetamines of the body can lead to serious health conditions, by taking time out this can be reduced and help the body recover.

- knowing the signs of overdose. If people can recognise the signs of overdose they can seek help or call an ambulance to prevent an overdose from causing irreversible harm.

Treatment

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

The current standard treatment for methamphetamine use is Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) [12, 76, 98, 99]. CBT involves a range of interventions, including coping skills therapy, relapse prevention and motivational interviewing. CBT is often delivered in residential rehabilitation services, outpatient counselling therapies and in group or individual treatment. Studies of CBT have shown that it produces small to medium reductions in methamphetamine use directly post-treatment, but in most studies the result was lost at six months follow-up [98, 100]. Brief interventions that are based on CBT approaches are also effective in reducing methamphetamine use. A specific manual has been developed for AOD workers to undertake CBT with clients who use stimulant type substances (including methamphetamines) [99, 101].

While CBT has been found to be effective in reducing methamphetamine use in the general population [101, 102], there have been no studies to date to assess its effectiveness among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who use methamphetamine. Despite this, the National Indigenous Drug and Alcohol Committee (NIDAC) as well as the Handbook for Aboriginal Alcohol and Drug Work recommend using CBT with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients [87, 99]. A study conducted by Bennett-Levy and colleagues [103] with Aboriginal counsellors, identified that CBT was highly appropriate and feasible to conduct with Aboriginal clients for multiple reasons. Firstly, the central approach to CBT is empowering clients to increase their sense of control (agency) and teaching the client to use their skills to take control over their lives and throughout therapy. This is in line with the aspiration of self-determination, central to improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Secondly, CBT is focused on the here-and-now and therefore has a focus on healing trauma, rather than re-traumatising through reliving past trauma through therapy. Finally, Aboriginal clients would share the techniques that worked for them with their family members who could indirectly benefit from the CBT [103]. While there have been no formal evaluations of the effectiveness of CBT to reduce methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients, the effectiveness of CBT among mainstream clients and the appropriateness of CBT for Aboriginal clients indicate that this is a promising treatment strategy [72].

Contingency management

Contingency management (CM) focuses on supporting people through their treatment or training by rewarding them for positive behaviours. Rewards can be vouchers, tokens or other incentives. The receipt of rewards can be dependent on attending counselling sessions or providing a drug free urine sample. Usually rewards include vouchers to the clients’ favourite store, cinema, events, or sports centres. The two most important elements of CM are that the rewards are provided immediately and the rewards increase with increased time off drugs [99]. CM is not as commonly used in Australia as CBT, but there is some evidence that CM increases attendance at treatment and reduces methamphetamine use during the treatment, but reduction in the use seems to disappear in follow-up [72, 100]. To date there have been no evaluations of CM among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who use methamphetamine, nor any study assessing the appropriateness and feasibility of this approach. However, because the clients receive tokens or voucher-based rewards, it can provide people who use methamphetamine with a diversion from drug use, which is likely to be effective for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients as well as non-Indigenous clients.

Community Reinforcement Approach and Family Training (CRA and CRAFT)

The Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) is a popular and effective cognitive behavioural intervention for substance use, primarily alcohol use [104, 105]. CRA works with the client to identify motivational factors for their substance use and motivational factors for non-using (including alternatives to using) and works with the clients to develop strategies to reward non-using and discourage use. The reward system can be similar to CM in that it uses vouchers or money, but ultimately the activity of non-using should be or become rewarding in itself. CM approaches can also be combined with CRA.

CRA Family Training (CRAFT) works with the family as well as the client by supporting the family to remove factors that reinforce substance use and promote factors that reinforce not using. There is evidence that CRA and CRAFT are effective in reducing substance use, including stimulant type substances [104-106]. The involvement of family in the treatment of methamphetamine use has been identified as a priority for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities [34, 72-74, 82, 107], and CRAFT is therefore likely to be appropriate to use with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients who use methamphetamines.

A study conducted by Calabria and colleagues [108] with Aboriginal clients of an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS), identified that delivery of CRA was highly acceptable among Aboriginal clients after alcohol withdrawal and that delivery of CRAFT was highly acceptable with family members or friends who wanted to support their loved one to start alcohol treatment. Following this study, both the CRA and CRAFT programs have been adapted from the American to the Aboriginal Australian context using an action research approach that involved health workers from a local ACCHS being trained in delivering the CRA and CRAFT programs to their Aboriginal clients [109]. The adapted manuals are available online (CRA: https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/resource/aboriginal-specific-community-reinforcement-approach-cra-training-manual; CRAFT: https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/resource/aboriginal-specific-community-reinforcement-and-family-training-craft-manual) [110, 111]. Similarly to CBT, while CRA and CRAFT have not been specifically evaluated for their effectiveness in reducing methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, their effectiveness among mainstream clients and their acceptability to Aboriginal community members in treatment of other substances make these promising treatment strategies.

Brief intervention and motivational interviewing

Brief interventions refer to a wide range of interventions that are brief in duration and often provided in an opportunistic way. Brief intervention is often combined with motivational interviewing. The aims of brief intervention and motivational interviewing are to engage people who are not ready for change, increase the person’s perception of real and potential risks and problems associated with their substance use and associated activities, and to encourage them to consider reasons for change and the negatives of not changing. Brief intervention has been found to be effective to reduce alcohol use [112], smoking [113] and cannabis use [114]. Special manuals have been developed to deliver brief intervention with people who use methamphetamine [115]. There is some evidence that providing brief intervention is effective in changing people’s intentions and attitudes associated with methamphetamine use and small reductions in use have been reported [116].

Brief intervention and motivational interviewing have been used with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to address alcohol use [117, 118] as well as mental health and cannabis treatment [107]. However, assessments of the success of these strategies in addressing alcohol use are mixed. Clinicians have indicated that they think the non-judgemental approach of motivational interviewing works well [118]. But discussing alcohol use is often regarded as a private issue and not everyone is keen to do so [118]. This is especially an issue when health professionals are also family, community members or friends [117, 118]. In those cases, health professionals are often not comfortable asking about the clients’ substance use, and clients have mentioned issues around confidentiality and trust [117, 118]. Furthermore, some Aboriginal clients have also indicated that they are interested in receiving feedback about their drinking, but not in receiving one-on-one counselling [117].

More positively, Nagel and colleagues [107] developed a brief intervention to address mental health and comorbid substance use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients. This intervention consisted of two one-hour treatment sessions. The sessions explored family support, strengths and stresses and goal setting. Psycho-education[2] was delivered using a video. The evaluation of the intervention showed that the brief intervention improved mental health and substance use outcomes compared to treatment as usual, and the improvement sustained over an 18 month period [107].

The NIDAC recommends using brief intervention to address methamphetamine use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [66]. This is based on the combined evidence of the effectiveness of brief intervention and motivational interviewing approaches with mainstream methamphetamine clients [116], and recent evidence shows the effectiveness of brief intervention to improve mental health and substance use outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [107]. The NIMAC study by Ward and colleagues [90] will develop therapeutic interventions based on motivational interviewing and CBT approaches (see Box 4).

Box 4. New and emerging programs: NIMAC study

As part of the NIMAC study led by Associate Professor James Ward (see Box 3), a web-based therapeutic intervention will be developed that uses CBT and motivational interviewing approaches. This intervention will be developed to be visual, interactive and culturally appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients and will be delivered by ACCHSs, combined with clinical support (face-to-face or via the phone) [90].

Residential rehabilitation

Residential rehabilitation is one of the most sought-after forms of treatment for people with methamphetamine use [98]. Residential rehabilitation services are abstinence-based, long-stay programs where clients stay at the facility, including therapeutic communities. While in residential rehabilitation, the client is removed from their usual environment, including triggers, influences and access to methamphetamines. Residential rehabilitation is often combined with other treatment models, including CBT. There is some evidence that residential rehabilitation is effective for methamphetamine use [98], for example in a recent Australian study methamphetamine use reduced substantially three months after return from treatment [120]. Further analysis of the data indicated that abstinence was associated with longer stay in residential rehabilitation (>90 days) and by receiving personal counselling sessions while in residential rehabilitation [68].

The effectiveness of residential rehabilitation has not been evaluated for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who use methamphetamine and there are mixed opinions in the literature about the appropriateness of residential rehabilitation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The importance of connection to family and community makes residential rehabilitation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people a less-than-optimal approach as it involves being away from family and community for lengthy periods of time [12, 34, 72, 73, 87].

However, some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have attended residential rehabilitation have found this a positive experience [23, 73, 87, 121]. Positive experiences were primarily related to Aboriginal community-led residential rehabilitation services in which culture and connection to Country were part of the treatment. For those places, clients identified that being out in the bush, being able to connect to Country and getting away from everything was important for their recovery [23, 73, 121]. Being in residential rehabilitation can also be beneficial for families to ‘get a break’ from their substance using family member [87].