Developing client information systems for social and emotional wellbeing workers

Brief reportReilly L (2019). Developing client information systems for social and emotional wellbeing workers. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 19(2) Retrieved [access date] from https://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/developing-client-information-systems-for-social-and-emotional-wellbeing-workers

Corresponding author: Lance Reilly, People Development Unit, Nunkuwarrin Yunti of SA Inc., ph: (08) 8168 8300, email: lancer@nunku.org.au, 80 South Terrace, Adelaide SA 5000.

Introduction

The role of Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) workers can be wide and varied, and this can present challenges for those who are employed within clinically-orientated health services. Among other things, many of the encounters that SEWB workers have with clients are difficult to classify within the patient information systems that are commonly used throughout the primary health care system, and are thereby difficult to report on in aggregate.

The SEWB worker is generally concerned with matters that fall beyond the realm of the medical model, or are at the outer reaches at least. Given that they are typically employed by Aboriginal community-controlled health services (ACCHSs), their opportunity for entering coded client data is invariably confined to that which is medically-orientated.

The incorporation of a more suitable classification system within ACCHS patient/client information systems is needed to enable SEWB workers to better record their activity in relation to working with their clients. This aspect is considered with reference to SEWB workers at Nunkuwarrin Yunti, an ACCHS in metropolitan Adelaide.

Role of the SEWB worker

The role of the SEWB worker is generally more difficult to define than that of a clinically-orientated Aboriginal Health Worker (AHW). Nowhere is this more starkly illustrated than by the fact that clinically-orientated AHWs who have completed a Certificate IV in Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care (Practice) are eligible for registration by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency’s (AHPRA’s), whereas SEWB-orientated AHWs who have completed a Certificate IV in Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care, or even a Diploma in Narrative Approaches for Aboriginal People, are not.

SEWB workers have been funded by the Commonwealth Government since around 1998, in response to the Bringing them home report’s recommendations relating to the mental health and wellbeing needs of the Stolen Generation and their families.1 The programs that ensued were orientated around counselling, case work and alcohol and other drugs, in accordance with the Commonwealth Department of Health former Bringing Them Home funding guidelines.2

SEWB workers are in a position to respond to various facets of a client’s wellbeing that might not ordinarily capture the focus and attention of their clinically-trained peers. Within South Australia at least, their job descriptions typically reflect service provision that is reflective of the holistic definition of health that was enshrined within the 1989 National Aboriginal Health Strategy, viz:

… not just the physical wellbeing of an individual but refers to the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole Community in which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being, thereby bringing about the total wellbeing of their Community. It is a whole-of life view and includes the cyclical concept of life-death-life [1].

An inherent problem with this definition is that it is more a definition of the broader notion of wellbeing than it is of health, and an implication of it is that the work of SEWB workers is viewed as being of a medical nature. Support for this view may be found in the fact that up until the finalisation of the Fifth National Mental Health Plan, social and emotional wellbeing was placed within a mental health framework; it has only been with the finalisation of the current plan that social and emotional wellbeing is recognised by the mental health fraternity as being much more than mental health.

The responsibilities and duties that are required of many SEWB workers in South Australia are broad; they can include: advocating for clients; engagement with a range of social health and welfare services on behalf of clients; and acting as a cultural broker between clients, their families and other services. Among other things, some SEWB workers are known to have advocated for clients in the courts.

In contrast to the role of the clinical AHW, the role of the SEWB worker is not always so easily defined and may therefore be prone to misconception and misunderstanding. Within the broad SEWB worker categories of ‘counsellor’, ‘case worker’ and ‘AOD worker’, it is the role of counsellor which is more aligned with the clinical model and is perhaps better understood by other clinicians. One of the consequences of the roles of the case worker and AOD worker not being so aligned appears to be that their activity is often difficult to classify within the client information systems that have been instituted within Aboriginal health services.

While the role of the SEWB worker is consistent with the holistic definition of Aboriginal health that has been espoused since the time of the National Aboriginal Health Strategy, role clarity and definition are important to both the SEWB worker and their employers. This can be improved through the employment of a client information system that provides for better classification of client data in relation to the activities of the SEWB worker.

Classification of social issues

The Aboriginal community-controlled health services that predominantly employ SEWB workers typically use Communicare, which is a patient information system that is based on a version of the International Classification of Primary Care, known as ICPC-2 Plus.

The ICPC-2 is medically orientated and is a ‘primary care adaptation’ of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) [2]. It contains a chapter on ‘social problems’, which enables a practitioner to identify some context for an encounter with a client/patient without having to record a medical diagnosis. There are thirty ‘social problems codes that a practitioner may select, including: Poverty/financial problem (Z01); Housing/neighborhood problem (Z03); Legal problem (Z09); Partner behaviour problem (Z13); Loss/death of parent/family member (Z23) and Assault/harmful event (Z25).

These items are relevant to SEWB workers, except that their selection says little about their impact upon a client’s health and wellbeing. For example, while the ICPC-2 Plus provides for the classification of ‘legal problem’, there are various types of legal problems, with different durations and potential consequences; and even if one client is facing the same legal problem as another, their impact could manifest differently within each.

Furthermore, while the impact upon a person’s health may be reflected in terms of other items within the ICPC-2 Plus classification system, the impact upon their overall wellbeing may not. Given that the role of the SEWB worker is, by definition concerned with a client’s social and emotional wellbeing, the ICPC-2 Plus classification system is necessarily limited for recording their activities in relation to such encounters.

Client contacts at Nunkuwarrin Yunti

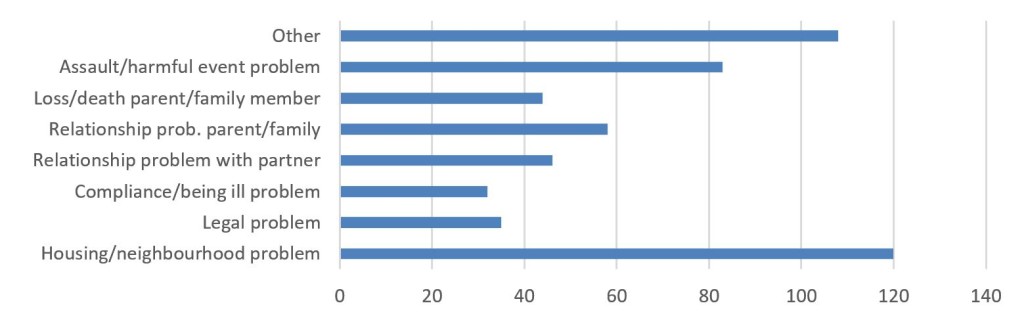

Figure 1, below, illustrates the number of coded social problems of Nunkuwarrin Yunti clients between the period 15/2/17 and 12/2/19. A total of 526 social problems (as classified under the ICPC-2) relating to 269 clients were recorded in Communicare, including 120 ‘housing/neighbourhood problems’, 83 ‘assault/harmful event problems’, 58 ‘relationship problems with parent/family’, 46 ‘relationship problems with partner’, 44 ‘loss/death of parent/family member problem’ and 36 ‘legal problems’ 32 and ‘Compliance/being ill problem’.

Figure 1: ICPC-2 coded social problems of Nunkuwarrin Yunti clients between 15/2/17 and 12/2/19

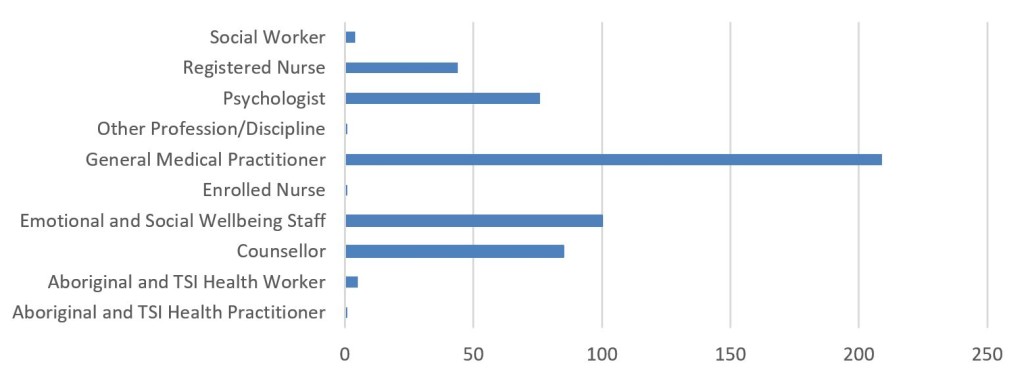

These numbers appear to be lower than expected, considering the complexity of issues that are generally known to be experienced by many of Nunkuwarrin Yunti’s clients. But at least, these types of issues are being recorded to some extent. What might be more surprising is the number of social problems that are being recorded by Aboriginal Health Workers/Practitioners, SEWB workers and counsellors, as illustrated by Figure 2, below.

These numbers are reflective of the fact that it is the GP who is typically the first practitioner to record data relating to the client’s social background. This is surprising given that AHPs and AHWs are typically the first to make contact with the client, however their role in this respect is said to be more centred on performing health checks.

The numbers attributed to SEWB staff and counsellors are much higher than those for AHPs and AHWs, although they have been entered mostly by two SEWB workers and two counsellors. A possible reason for this distinction might be that while the clinical AHP/AHW is working closely with the GP and other clinical workers, the SEWB worker is not. Nevertheless, the SEWB worker has access to records of clients who have presented to the clinic previously and these records may already include the identification and coding of a social problem(s). Indeed, the client may have been referred to the SEWB worker by the clinic.

Figure 2: Number of ICPC-2 coded social problems contacts recorded at Nunkuwarrin Yunti by occupation between 15/2/17 and 12/2/19

Notwithstanding, the number of times that SEWB workers have coded a social problem that is being faced by a client still appears to be very low. A possible explanation of this may be that the coding of a social problem relating to their client does not offer much by way of utility to the SEWB worker.

The ‘social problems’ chapter of the ICPC-2 does little more than flag some issues pertaining to the client. In addition, it does little to inform the decision maker about a client capability and functioning, at either a client-level or population-level.

Functioning and capability

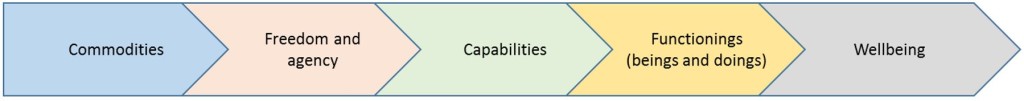

The functioning and capability paradigm provides a normative framework for the evaluation of wellbeing. The Capability Approach was developed by Amatya Sen in response to the failure of conventional approaches to the evaluation of wellbeing in factoring in things such as the varying capabilities of people to convert resources into valuable functionings and the propensity for people to internalise and normalise the harshness of their circumstances [3].

Functionings are ‘beings’ and ‘doings’ that a person undertakes (such as being well nourished, being educated, driving a car and having shelter) and capabilities are sets of valued functionings that a person is really able (or free) to achieve (such as the ability to be well nourished and the ability to be educated). Essentially, the Capability Approach considers what people are able to do and what they are able to be. It provides for people using their available capability sets to achieve the things that they have reason to value.

Sen’s notion of freedom (to achieve) has two elements. The first related to opportunities or the ‘substantive freedoms’ that the members of a society enjoy. The second relates to empowerment and agency, which he calls ‘process freedoms’; these is the freedom for the individual to be and do things that they themselves value [4].

Agency refers to as someone who acts and brings about change, whose achievement can be evaluated in terms of his or her own values and goals. Agency typically refers to a person’s role as a member of society, with the ability to participate in economic, social, and political actions.

Freedom and agency depend on personal and environmental factors. The relationship between the key elements is illustrated in Figure 3, below.

Figure 3: Elements of the Capability Approach and their relationship

Significantly, the functioning and capability paradigm has been incorporated into the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), which presents another reason to pay it some regard.3

The notion of functioning has also been incorporated into Australia’s Indigenous social welfare policy lexicon, in relation to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework [5], and in respect to the justification of some of the Federal Government’s more paternalistic policies that were promulgated in relation to the Cape Yorke Reform Trials. In respect to the latter, Sen’s Capability Approach has been employed in little more than name only [6], however the former explicitly recognises the importance of community functioning to maintaining and improving the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Themes identified within the Health Performance Framework in relation to community functioning include: ‘connectedness to country, land and history, culture and identity’;4 ‘resilience’;5 ‘leadership’;6 ‘having a role, structure and routine’;7 ‘feeling safe’;8 and ‘vitality’.9 Indeed, these are the types of matters that SEWB workers are often concerned with and yet the client information systems that they typically use do not accommodate them to any great extent.

In developing a client information system that is responsive to the informational needs of SEWB workers, the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) offers at least one option for consideration.

International Classification of Functioning

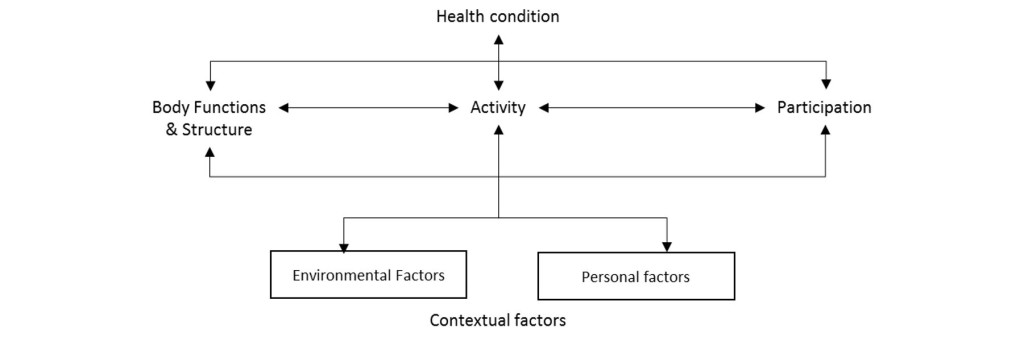

The ICF was endorsed by the WHO in 2001 ‘to obtain a comprehensive perspective of health and functioning of individuals and groups’ [7]. It is based on the model outlined in Figure 4, below.

Figure 4: Interactions between the components of ICF

The ICF is organised into two parts, viz: functioning and disability; and contextual factors. The functioning and disability part is comprised of ‘body functions and structures’, ‘activities’ and ‘participation’. Contextual factors incorporates ‘environmental factors’ and ‘personal factors’, although personal factors are yet to be classified [8].

Identification of the contextual factors offers the prospect of developing a more complete understanding of not only an individual’s state of functioning and variation in experiences [7], but also the state of a community’s functioning if aggregated across a community.

Activities and participation classification codes relate to engagement in ‘organized social life outside the family, in community, social and civic areas of life’. Environmental factors are classified in relation to ‘products and technology’, ‘natural environment and human-made changes to environment’, ‘support and relationships’, ‘attitudes’ and ‘services, systems and policies’; these may present as either a facilitator or a barrier to an individual, depending on their circumstances [9].

The subjective and relational nature of assessment against the ICF may be off-putting to those seeking to use it in its own right. Among other things, the ICF has been criticised for being an inadequate tool for the assessment of functional impairments common with most mental health issues [10]. On the other hand, the exclusive use of a medical/disease orientated classification system does not offer a complete solution either; eg, in respect to the Closing The Gap initiative’s dedicated focus on achieving equality with non-Indigenous life expectancy, the 2010 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework introduced the concept of functioning and observed that this measure was on quantity of life rather than quality [11].

However, if the ICF is used in combination with a classification system such as the ICPC-2, the resultant reports on each client could provide a much richer picture of the client’s situation and needs than using a system that is constructed exclusively upon either the ICF or the ICPC-2.

Measurement and scoring

Incorporation of the ICF would allow for the measurement of a client’s level of functioning in respect to their agency and values.

There are different types of Aboriginal communities across the continent with a common basic differentiation being made between urban, rural and remote. There are also differences in functioning within these communities, which are based on each person’s circumstances and outlook. The selection of functionings that are based on the client’s values promotes a person-centric approach, which seeks to empower them in the process of improving their wellbeing.

Without this commitment to promoting and supporting client agency, the incorporation of the ICF will look something more akin to the NDIS, through its adoption of the WHO Disability Assessment Tool (WHODAS). This instrument scores the achievement of six domains of functioning10 in terms of ‘difficulty’, against which an assessment of a client’s level of disability can be assessed. This approach lends itself to comparability of selected need across all clients, however it does not necessarily identify those things which might make a difference in a client’s life in their particular circumstances as it defeats the goal of agency and the freedom to achieve [3,12]. Furthermore, much of the thinking to date in regard to the ICF’s application has been around disability, or what the client can’t do or be. But it can also be used to identify what a client can do or be.

SEWB workers require a more open system that encourages a more opportunistic approach for information to be collected through conversation and engagement with the client, and then classified against the ICF.

The functioning paradigm introduces the notion of agency as a useful endeavour in and of itself and while the health system is seeking to become more person-centric, its conception in the health arena has been limited to the client’s interaction with the health system.

Instead of a scoring system that is measures ‘difficulty’ (per the WHODAS), full utilisation of the ICF could score functionality according to the following scale:

0 = fully dysfunctional

1 = somewhat dysfunctional

2 = neither functional nor dysfunctional

3 = somewhat functional

4 = fully functional.

Importantly, the ICF and the ICPC can be utilised concurrently, to provide a much richer source of information than the use of either classification system in isolation [13]. Thus, the ICF should be incorporated into patient information recall systems that are used within Aboriginal health services.

Development of information systems

Today, most ACCHSs utilise Communicare. This and another system, known as Ferret, were developed with financial support from the then Department of Health & Ageing from the 1990s.

Communicare and Ferret were developed as patient information recall systems in accordance with specifications and with funding from the Commonwealth Department of Health & Ageing from the 1990s. The intention was to create a system that enabled opportunistic care, particularly in relation to people with chronic disease (which is widespread amongst Aboriginal people). Communicare ultimately prevailed as the system of choice amongst the vast majority of Aboriginal community-controlled health services (including Nunkuwarrin Yunti), although the original duopoly is no longer supported by funding from the Department.11

There is some conjecture as to how much value-for-money the Department and its funded constituents received from this venture, however the ACCHS sector at least has an effective system for classifying episodes of care against the ICPC-2 Plus and for recalling patients with chronic disease in an opportunistic manner to provide more effective care.

The Federal Department of Health could do something similar again to assist the development of patient information recall systems that accommodate the breadth of activities that are performed by SEWB workers through incorporation of the ICF.

References

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party, National Aboriginal Health Strategy, 1989, Canberra, in National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023, Commonwealth of Australia, p.9, http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/B92E980680486C3BCA257BF0001BAF01/$File/health-plan.pdf

- WHO, Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF, WHO, Geneva, 2002, p.4, https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

- ‘Sen’s Capability Approach’, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://www.iep.utm.edu/sen-cap.

- Klein, E., A critical review of the capability approach in Australian Indigenous policy: Working Paper No. 102/2015, ANU, 2015, p.2., http://caepr.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/Publications/WP/WorkingPaper102_2015_Klein.pdf (8/8/16).

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 Report, AHMAC, 2017, https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/2017-health-performance-framework-report_1.pdf

- Klein, E., A critical review of the capability approach in Australian Indigenous policy: Working Paper No. 102/2015, ANU, 2015, p.4., http://caepr.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/Publications/WP/WorkingPaper102_2015_Klein.pdf (8/8/16).

- Alford, V.M., Remedios, L. J., Webb, G.R. & Ewen, S., ‘The use of the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) in indigenous healthcare: a systematic literature review’, Int J Equity Health. 2013; 12: 32, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3735045

- World Health Organization, How to use the ICF: A practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): Exposure draft for comment, WHO, Geneva, October 2013, p.28, https://www.who.int/classifications/drafticfpracticalmanual2.pdf?ua=1

- ICF online browser, ‘d9 Community, social and civic life’, http://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser

- NDIS, IAC advice on implementing the NDIS for people with mental health issues, https://www.ndis-iac.com.au/support-people-with-mental-health-issues

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report 2010, 2011, AHMAC, Canberra. p.40, http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/health-oatsih-pubs-framereport-toc/$FILE/HPF%20Report%202010august2011.pdf

- The Capability Approach, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2011, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/capability-approach

- Veitch, C., et al, Using ICF and ICPC in primary health care provision and evaluation, WHO, 2009, https://www.who.int/classifications/network/WHOFIC2009_D009p_Veitch.pdf

Footnotes

1 Most notably, recommendations 33a, 33b, 33c and 35.

2 The Bringing Them Home appropriation has since been rolled into the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (administered by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet) which does not make any specific reference to social and emotional wellbeing within its program guidelines. However, the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet has continued to fund the SEWB program along the lines that the Department of Health did.

3 The WHODAS assessment, which is employed by the NDIA, is based on the ICF.

4 Being connected to country, land, family and spirit; a strong and positive social networks with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; a strong sense of identity and being part of a collective; sharing; giving and receiving; trust; love; looking out for others.

5 Coping with the internal and external world; power to control options and choices; ability to proceed in public without shame; optimising what you have; challenge injustice and racism, stand up when required; cope well with difference, flexibility, accommodating; ability to walk in two worlds; engaged in decision-making; external social contacts.

6 Strong elders in family and community, both male and female; role models, both male and female; strong direction, vision; the ‘rock’, someone who has time to listen and advise.

7 Having a role for self: participation; contributing through paid and unpaid roles; capabilities and skills derived through social structures and experience through non-formal education; knowing boundaries and acceptable behaviours; sense of place–knowing your place in family and society; being valued and acknowledged; disciplined.

8 Lack of physical and lateral violence; safe places; emotional security; cultural competency; relationships that can sustain disagreement.

9 Covers community infrastructure, access to services, education, health, income and employment.

10

(i) Cognition – understanding & communicating

(ii) Mobility– moving & getting around

(iii) Self-care– hygiene, dressing, eating & staying alone

(iv) Getting along– interacting with other people

(v) Life activities– domestic responsibilities, leisure, work & school

(vi) Participation– joining in community activities

11 Communicare is now owned by Telstra.