Review of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

ReviewColonna E1, Maddox R1, Cohen R1, Marmor A1, Doery K1, Thurber K A1, Thomas D2, Guthrie J1, Wells S1, Lovett R1

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program, National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University.

- Menzies School of Health Research.

Corresponding author: Emily Colonna Emily.Colonna@anu.edu.au, 54 Mills Road Acton ACT 2601 ph: +61 2 6125 8417

Suggested citation:

Colonna. E., Maddox, R., Cohen, R., Marmor, A., Doery, K., Thurber, K. A., Thomas, D., Guthrie, J., Wells, S., Lovett R. (2020). Review of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin, 20(2). Retrieved from https://aodknowledgecentre.ecu.edu.au/learn/specific-drugs/tobacco/

Download PDF 2.9MB

Contents

Introduction

About this review

Acknowledgements

Key facts

Tobacco use

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population

The context of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Extent of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia

How smoking affects your body and health

Tobacco-related disease burden

Tobacco-related mortality

Impact on community and culture

Factors related to tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

National policies and strategies impacting tobacco use

Tobacco control policies and their impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Policies related to tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Programs to address tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Opportunities in addressing tobacco use

Concluding comments and future directions

Appendix 1: Glossary and acronyms

Appendix 2: Smoking and health conditions

Appendix 3: Literature search strategy

References.

Introduction

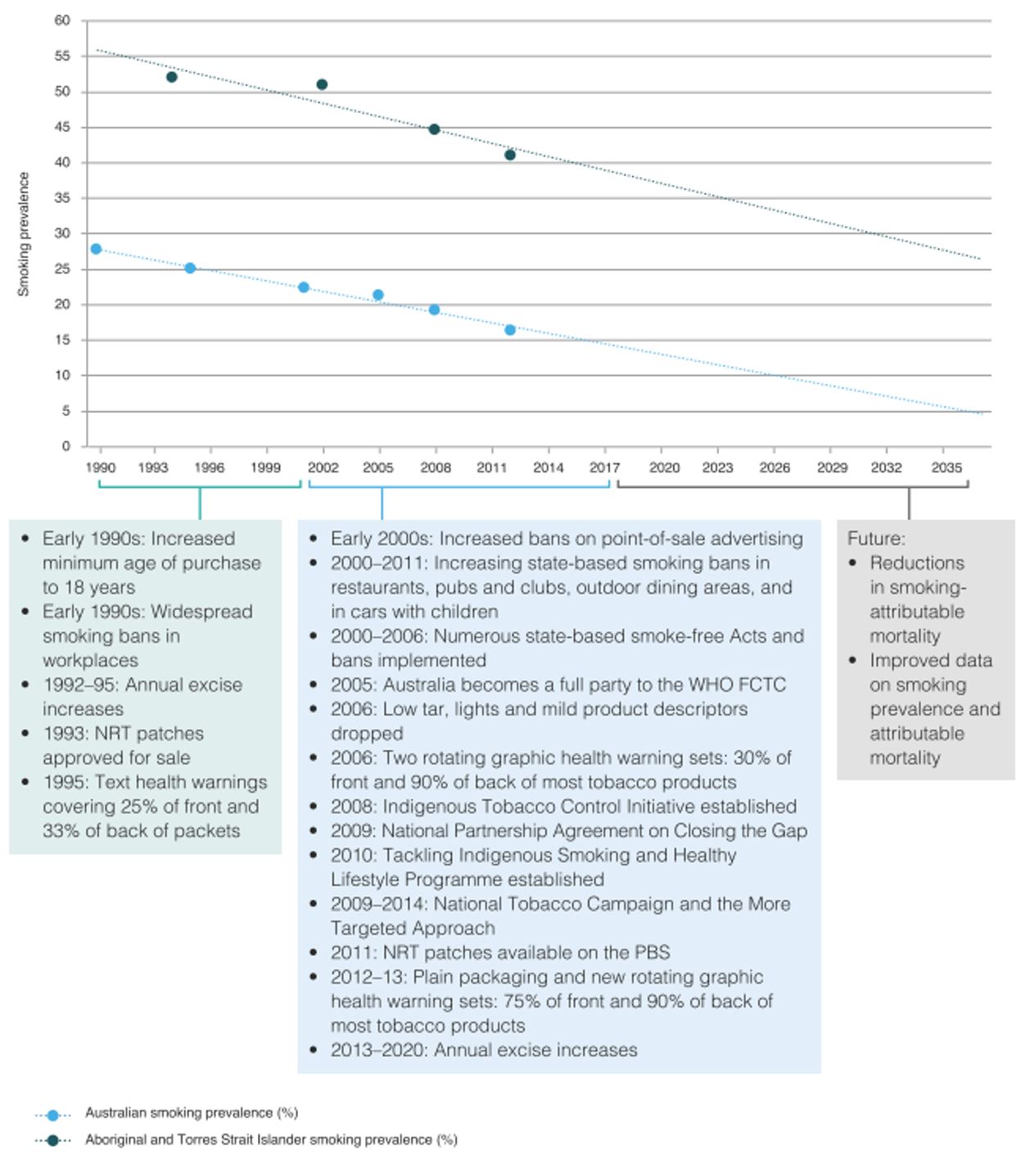

Tobacco use is the leading contributor to the burden of disease for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and is both an issue of great concern and an area for considerable health gains [1]. Reducing tobacco use is achievable. Substantial progress has already been made, with a 9.8 percentage point reduction in the prevalence of daily smoking for those aged 18 years and over from 2004–05 to 2018–19 from 50.0% to 40.2% [2]. This is a promising development, after a period of limited change in the preceding decade [3]. Further reductions in tobacco use will continue to enhance the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

This review takes a strengths-based approach to examine tobacco use in detail, specifically in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context. Often, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health is viewed through comparative statistics with the non-Indigenous population which can reproduce deficit discourse [4, 5]. These comparisons can also obscure the diversity of nations, cultures, perspectives, languages and experiences that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples represent. This review moves beyond comparison to understand Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ tobacco use in context. Unless explicitly stated, literature and evidence presented are specific to the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander population.

Context is vital to accurately and meaningfully understand tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Beyond establishing the existence of health gaps and substantial opportunities for improvement, it is important to understand the mechanisms by which inequities arose and endure [6]. Within the diversity, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples share a common history of colonisation, with negative impacts that continue today [6-8]. As such, the review situates tobacco use within the contexts of enduring and evolving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ cultures and societies, historical and contemporary trauma, tobacco industry interference and the social and cultural determinants of health.

This contextualisation is also important to avoid reproducing deficit discourse or colonialist ways of knowing and doing that focus on ill health and disadvantage [9]. Contextualisation can assist in addressing the inaccurate and misleading notion that there is a biological basis for the higher rates of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared with other Australians. This includes fallacies that Indigenous peoples are genetically or biologically predisposed to addiction. These notions are a form of deficit discourse based on ideas of racial inferiority [5] and there is no evidence to support these claims.

Finally, the review acknowledges the complexity of tobacco use. It expands beyond the binary of smoker/non-smoker to examine a range of behaviours relating to tobacco use, including: initiation, smoking, attitudes, starting quit attempts, successful cessation and second-hand smoke exposure.

These approaches to understanding the literature will assist in determining what is known about tobacco use, what has worked to reduce tobacco use, and what can be done in the future to further enhance the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

About this review

The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of key information on tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia to:

- inform those involved or who have an interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, in particular tobacco use, and

- provide the evidence for policy, strategy and program development and delivery.

The review provides general information on the historical, social and cultural context of tobacco use, and the factors that contribute to tobacco use. It provides information on the extent of tobacco use, including: incidence and prevalence data; hospitalisations and health service utilisation and mortality. It discusses the issues related to tobacco use, and provides information on relevant policies and strategies that address tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It concludes by discussing possible future directions in Australia.

Evidence shown is mainly focused on smoking commercial cigarettes as these are the primary cause of tobacco-related harm and the focus of available data sources. However, as this focus does not capture the extent of tobacco use, the review includes evidence on chewing tobacco and electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) where available.

This review takes a human rights and social justice approach. Specifically, the review is underpinned by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) [10, 11]. This acknowledges that ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination’ [10, p.4] and recognises the disproportionate harm caused by commercial tobacco to Indigenous peoples [11]. Consistent with National Health and Medical Research Council Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders 2018 and Keeping research on track II 2018, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were involved in all aspects of the review [12, 13].

This review draws mostly on journal publications, government reports, national data collections and national surveys, the majority of which can be accessed through the HealthInfoNet’s publications database (http://aih-wp.local/key-resources/publications). Information specifically about tobacco use is available at: http://aod-wp.local/learn/specific-drugs/tobacco

Edith Cowan University prefers the term ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ rather than ‘Indigenous’ for its publications. However, when referencing information from other sources, authors may use the terms from the original source. As a result, readers may see these terms used interchangeably with the term ‘Indigenous’ in some instances. If they have any concerns, they are advised to contact the HealthInfoNet for further information.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are extended to:

- the anonymous reviewer whose comments assisted finalisation of this review

- staff at the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet for their assistance and support

- the Australian Government Department of Health for their ongoing support of the work of the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet

- Glen Benton, Partnerships Officer – Aboriginal Quitline, Quit Victoria, for his feedback on the impacts of colonisation and future directions of this review.

Key facts

- Colonisation is an important factor contributing to tobacco use. Tobacco was introduced (and its use entrenched) by colonisers. In addition, colonisation led to ongoing trauma, stress, racism and exclusion from economic structures, and these factors are all associated with tobacco use.

- Tobacco use is the leading contributor to the burden of disease for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and therefore, there is substantial potential for health gains through reducing tobacco use.

- Smoking harms almost every organ and body system. Most of the tobacco-related harm comes from atherosclerotic diseases (mainly coronary heart disease), cancers, chronic lung disease, and type 2 diabetes.

- Quitting smoking (or never smoking at all) is important. Quitting smoking at any age can reverse the health risks linked to smoking, and the earlier you quit, the better.

- Evidence shows that people want to quit. Sixty-nine percent of people who smoke daily had ever made a quit attempt, and 48% had made a quit attempt in the past year. Quitting smoking is supported by: knowledge of the health impacts of smoking – both for the smoker and those around them; denormalisation of smoking; support of family and friends; and wanting to be a role model for family and community.

- Reducing tobacco use is achievable and substantial progress has already been made, with a 9.8 percentage point reduction in the prevalence of adult daily smoking since 2004. This will lead to substantial health gains.

- Current daily smoking prevalence for adults (aged ≥18 years) is 40.2%. Smoking is less common among younger adults compared with older adults. Smoking is also less common in those living in urban and regional areas compared with those living in remote areas.

- Community, health services and governments are running a range of programs to support people to quit smoking, to never start smoking, and to reduce exposure to second-hand smoke. Effective programs are culturally appropriate and use holistic approaches to address the complex issue of tobacco use.

- Programs to address tobacco use could be strengthened through expanded coverage, long‑term funding, and rigorous evaluation evidence.

- Continued vigilance is required to restrict the tobacco industry’s promotion of tobacco use and its attempts to undermine policies and activities to reduce tobacco use.

Tobacco use

Nicotine

A key factor for why people smoke is the enjoyment it provides [14]. Smoking can help people to feel alert, happy, relaxed and good. Inhalation of nicotine triggers the release of psychoactive neurotransmitters, such as dopamine which influences smoking behaviour via pharmacological feedback. These neurotransmitters produce a rewarding effect for the user and are the basis of the mood altering effects of nicotine [15].

Nicotine dependence is an important factor in why people continue to smoke and have difficulties quitting [15]. Subsequent nicotine exposure reinforces the pleasurable effects which causes tolerance via neuroadaptation and leads to dependence. Once dependent, people then smoke to avoid the undesirable symptoms of withdrawal, for example anxiety and stress.

Definitions

This review uses the term ‘tobacco use’ to include multiple kinds of tobacco use and exposure that impact the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. These include:

- Commercial tobacco

- Second-hand smoke exposure

- Tobacco use also includes the exposure of others to second-hand smoke. The smoke inhaled and exhaled by the smoker (mainstream smoke) and the smoke created by the burning of the cigarette (sidestream smoke) contain a similar range of chemicals, however they differ in the proportions and absolute amount of chemicals. Sidestream smoke is three times more toxic than mainstream smoke, containing double the amount of nicotine and carbon monoxide and 15 times more formaldehyde than mainstream smoke [17, 18].

- Native tobacco (pituri, bush tobacco)

- While the importation of commercial chewing tobacco has been banned in Australia since 1991 [19], there are several plants containing nicotine that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in some parts of Australia have historically used, and in some cases continue to use.

- These plants include bush tobaccos and pituri and are not smoked, but chewed and held in the mouth or stored elsewhere on the body, where the nicotine is absorbed through the skin [20-22].

- E-cigarettes

- E-cigarettes are battery operated devices that heat a liquid which produces an inhalable vapour. The liquid varies in composition, typically containing solvents and flavouring agents, and may or may not contain nicotine. It is illegal to sell e‑cigarettes that contain nicotine in Australia [23].

Although the ABS do not include native tobaccos or e-cigarettes in their definition of smoking, both are relevant to reporting tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population

In 2019, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population was estimated at 847,190 people and comprised 3.3% of the total Australian population [24]. Of this, 91% were Aboriginal, 5% were Torres Strait Islander and 4% were both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander [25].

The population is highly dispersed across the country. The largest number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people live in New South Wales (NSW) (281,107), and Queensland (Qld) (235,962) and the smallest number live the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) (8,178) [25]. Despite smaller numbers in the Northern Territory (NT), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples make up the highest proportion, 32% (77,605 people), of the population of all the states and territories. Conversely, Victoria (Vic) has the lowest proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 0.9% (62,074 people). Two thirds (64%) of Torres Strait Islander people live in Qld with the second largest number of Torres Strait Islander people living in NSW at 15%.

The population is a young population. The median age is 23 years with 33% of the population aged under 15 years and 4.9% aged 65 years or over [24, 26].

Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait people live in major cities and regional areas. In 2016, more than a third (37%) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples lived in major cities, 44% lived in regional areas, and 19% lived in remote areas [25].

The context of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Pre-colonial use of tobacco

There are limited documented accounts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ use of tobacco prior to colonisation. Existing accounts indicate that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples did not smoke tobacco, but in some areas of Qld, Western Australia (WA) and NT, people chewed the leaves of nicotine-containing plants, including pituri (Duboisia hopwoodii) and over twenty species of bush tobacco (Nicotiana spp.) [21, 27, 28] (see Chewing native tobacco for more information).

From around 1700, Macassan fishermen from the Indonesian island now known as Sulawesi traded tobacco and pipes with Aboriginal people from the Kimberley region of North West WA to the Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Qld to facilitate relationships and for permission to fish in their waters [27, 28]. Tobacco smoking was also introduced into Cape York and the Torres Strait region prior to the 1800s, though it is not known by whom [28, 29]. Given that tobacco was only available in certain seasons, it is unlikely that smoking tobacco would have been habitual during this period [27, 28]. Further, it is likely that people in south-eastern Australia did not use tobacco prior to colonisation [30].

Colonial introduction to tobacco

From 1788, European colonisers introduced British tobacco across Australia [28]. Tobacco was often used in first encounters between colonisers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as a gesture of goodwill [27, 28, 31, 32]. In diaries and letters, colonists describe carrying tobacco to give to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to assist in establishing relationships [33]. In the early 20th century, a chief protector of Aborigines, W.G. Stretton described tobacco as a ‘civilizing influence’ and as a way of eliciting help from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [34]. He wrote:

There can be no better civilising influence than that of continually moving about among the various tribes, each time taking a little tobacco or coloured cloth. How often has the weary traveller had to trust to the natives for a drink of water! [34]

Once introduced to tobacco, it became a highly desired good and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples actively sought it from colonisers [27, 28, 31, 33].

This desire for, and addiction to tobacco was exploited by colonisers to advance their economic, political and social goals [35, 36]. Colonisers often used tobacco as an inducement to labour. In many instances, providing labour in exchange for tobacco meant living in settlements or on missions and adopting European ways of living – including conversion to Christianity [27, 28, 30, 36]. Tobacco was also provided as a part of government and employer rations, which continued until the 1940s, and on some cattle stations until 1968 [37]. Addiction to tobacco acted as a form of bondage as people became more dependent on the rations, including tobacco [33].

Tobacco was also used as an enticement to procure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural and intellectual property [27, 28, 30, 36]. Scientists, collectors, and missionaries offered tobacco in exchange for items of material culture, instruction in languages, photographs, stories, witnessing ceremonies, and information about plants and animals. Geologist and anthropologist Charles Chewings (1859–1937) noted: ‘If you desire some article they possess and value you can offer nothing more tempting than tobacco in exchange for it’ [38, p.30].

While it is documented that some Aboriginal communities in the NT, Qld and NSW enacted agency in trading tobacco, the unequal power structures meant that the relationships were ultimately detrimental to them [33]. This detriment was partially intentional or known, in that colonisers knowingly used the addictive nature of tobacco to manipulate people and extort labour, goods and services. It also disrupted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ culture and connection with Country. Beyond these damages, the introduction of tobacco was detrimental to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health, though the extent of the health effects of tobacco use were not known during the early colonial period [33]. The use of tobacco by colonisers served to entrench tobacco use in the population, disrupting the culture, exploiting labour and causing harms to the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Further, it is likely that these processes contributed to widespread use of tobacco by both males and females from the beginning of the tobacco epidemic [33].

In the twentieth century, the use of tobacco by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples expanded dramatically [39] with the increasing power and mass-marketing of the tobacco industry, in spite of growing evidence of the harms caused by tobacco in the second half of the century [19, 40].

Extent of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia

Smoking prevalence

The most recent, nationally-representative estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking behaviours come from the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) [2]. In this survey, current smoking refers to regular smoking of cigarettes, cigars, pipes or other tobacco products [16]. Current smoking includes those who smoke daily (current daily smoking) and those who smoke less than daily (current less-than-daily smoking). When reporting contemporary (2018–19) smoking prevalence, this review presents data for current smoking, as well as the breakdown by daily smoking and less-than-daily smoking.

The earliest data on smoking prevalence comes from the 1994 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey (NATSIS). In this survey, data was only collected on current smoking of any amount (that is, daily and less-than-daily combined). So in this review, when describing long-term trends in smoking prevalence, from 1994 to 2018–19, the prevalence of any current smoking is reported. When describing recent smoking trends, focusing on the last 15 years, only current daily smoking is reported. This is because key national targets around smoking are based on current daily smoking [41, 42]. The vast majority of current smokers do smoke daily, and daily smoking is associated with the strongest negative impacts, compared with less frequent smoking.

In the 2018–19 NATSIHS, the prevalence of current daily smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (aged ≥18 years) was 40.2%, and the prevalence of current or less-than-daily smoking was 3.2%. This combines to a total adult current smoking prevalence of 43.4% [2]. Current smoking (daily and less-than-daily combined) prevalence was 39.3% among those aged 18–24, 47.5% among those aged 25–34, 49.8% among those aged 35–44, 44.9% among those aged 45–54, and 35.6% among those aged ≥55 years. Prevalence was similar for males (45.6%) and females (41.2%). Prevalence was lower among those in non-remote settings (39.6%) compared with those living in remote areas (59.3%) [2].

There has been a significant and substantial decrease in adult current smoking prevalence since 1994. Overall, current adult (aged ≥18 years) smoking prevalence decreased by 11.1 percentage points, from 54.5% in 1994 to 43.4% in 2018–2019 [2, 43]. There was relatively minimal change in smoking prevalence between 1994 and 2004–05 [3]. However, there have been recent substantial decreases in smoking prevalence. From the period of 2004–05 to 2018–19, daily smoking prevalence decreased by 9.8 percentage points (95% Confidence Interval: 6.7 to 11.5 percentage point decrease) among adults aged ≥18 years, from 50.0% to 40.2% [2, 44].

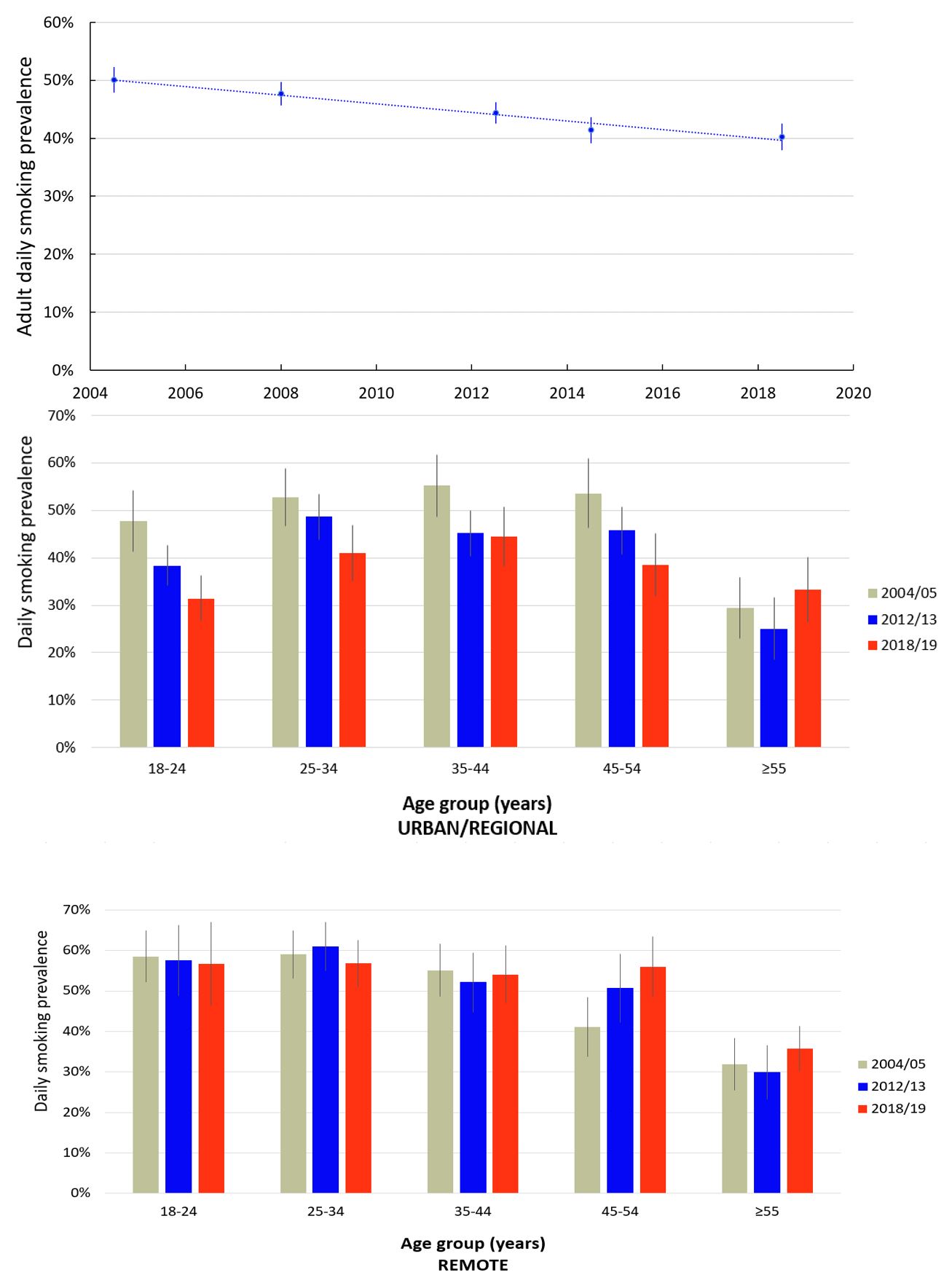

Substantial decreases in daily smoking prevalence from 2004–05 to 2018–19 were observed in younger age groups, with a 14.7% decrease for those aged 18–24 years, 10.6% for those aged 25–34, 8.5% for those aged 35–44 years and 8.7% decrease for those aged 45-54 years [2, 44]. No significant change was observed among people aged ≥55 years.

From 2004-05 to 2018-19, there was a 12.0 percentage point decrease (95% CI: 8.0,14.0) in daily smoking prevalence in non-remote settings. There was no significant change observed for those living in remote areas (0.1% increase, 95% CI: -5.2, 2.5) [44]. Research is needed to understand what underlies reductions in smoking prevalence in non-remote settings, and what is required to support declines in smoking prevalence in remote areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Estimated prevalence of daily smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults by age and remoteness group, 2004–5 to 2018–19

Source: Maddox et al. (2020 in progress) [44] and ABS (2019) [2].

Smoking initiation

There is evidence that young adults are initiating smoking later. Analysis of data from the 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) and the 2004–05 NATSIHS found a decrease in the percentage of 18–24 year olds who smoked began smoking daily before the age of 18 (from 84% in 2004–05 to 76% in 2014–15) [45].

Smoking during pregnancy

There has been a substantial decline in smoking during pregnancy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. It is estimated that 44% of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander mothers who gave birth in 2017 smoked during their pregnancy [46]. While this rate is high, there has been a substantial decline of 8 percentage points compared to 2009 rates of 52%. Smoking during pregnancy was less prevalent in major cities (38%) compared with remote (48%) and very remote (55%) areas. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are motivated to quit smoking during pregnancy and are making quit attempts (see Factors related to quitting for more information) [47, 48].

Second-hand smoke

Second-hand smoke releases thousands of chemicals into the environment [17]. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples live in homes with people who smoke. In the 2014–15 NATSISS, it was reported that 57% of children aged 0–14 years, and 60% aged 15 years and over, lived in a household with someone who smoked [49]. While many people smoke outdoors to limit the impact of their smoking on others, the 2014–15 NATSISS found that some people live with someone who smokes inside. The survey found that 13% of children and 19% of people over 15 years of age lived in home where people smoke inside.

Research has shown that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are making changes in smoking behaviour to reduce the impact of second-hand smoke on other people, particularly children [50-52]. In the Talking about the Smokes (TATS) study, 53% of daily smokers reported that smoking was not permitted inside their home [53]. In a qualitative study in NSW, parents expressed strong ideas about protecting their children from second-hand smoke including: stopping other people smoking in their homes, avoiding social situations where people would be smoking, smoking outside and changing clothes after smoking [50].

Chewing native tobacco

In some parts of Australia, largely in Qld, the NT and WA, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people use, and have historically used native plants containing nicotine. Bush tobacco (Nicotiana spp.) is prepared by drying the leaves, mixing them with ash to make nicotine available, and chewing to form a ‘quid’. Quids are then either held in the mouth or stored on the body – often behind the ear – where the nicotine is absorbed through the skin [20-22]. Bush tobaccos contain roughly 1% nicotine [27]. They were historically widely prepared, were used by men, women and children, and continue to be used and traded today [28].

Pituri, (D. hopwoodii) is another form of native tobacco which is prepared and used similarly to bush tobacco. It is a powerful stimulant, containing up to 8% nicotine. Pituri was a valued commodity and its production, distribution and consumption was constrained by social control mechanisms. Knowledge of processing pituri was vested in older males of particular groups in South Western Qld, where most of Australia’s pituri was processed, but it was traded widely [27, 28]. Use of pituri declined as the methods of preparation were lost during the period of early colonisation [28]. While a range of names exist for chewing native tobacco, in some places, the term ‘pituri’ has come to describe all chewing tobacco plants [21, 27, 28].

Chewing tobaccos were (and are) used to enhance mood, to suppress appetite, to reduce stress and pain, and to facilitate and maintain relationships through sharing [20, 21, 27, 28].

There is limited research on contemporary use of chewing tobacco, though its use is understood to be high in some regions of Australia [20]. For example, in Central Australia, high levels of chewing tobacco use were reported particularly among women, with young girls starting to use it between the ages of five and seven years [21]. A study in the Kimberley region of WA found that 39% of participants reported current use of chewing tobacco [54]. This was higher than commercial tobacco use at 35%.

E-cigarettes

There is limited research on the prevalence of e-cigarette use within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. Analysis of the TATS study found that one in five (21%) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants had tried e-cigarettes, compared with 31% of the national population [55, 56]. This may be attributable to relatively low awareness of e-cigarettes, with 38% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants reporting to have never heard about e-cigarettes [55]. E-cigarette usage was collected in the NATSIHS for the first time in 2018–19, however, prevalence estimates have not yet been published from these data.

Some studies have looked into the effectiveness of using e-cigarettes as a cessation tool, however the quality of the evidence is low [57, 58]. Further, there is evidence that e-cigarettes are harmful to health and may be linked with future smoking behaviour (see below for more information). As such, many health organisations state that there is insufficient evidence to support use of e-cigarettes as a cessation tool [59, 60].

How smoking affects your body and health

Exposure to the products of tobacco combustion and nicotine from past and current smoking, second-hand and third-hand smoke, and exposure in-utero has detrimental effects across the lifespan. Smoking harms almost every organ and body system. However, quitting smoking has immediate and long-term benefits, regardless of how long a person has been smoking [40].

This section summarises the health effects of tobacco use however, the information on the breadth and magnitude of the effects of smoking on specific health conditions is drawn from studies of non‑Indigenous populations, as the evidence from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations is sparse. Appendix 2 summarises key evidence from studies with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. For more detailed information on the health effects of smoking, see Tobacco in Australia [19], and the US Surgeon General’s report The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 years of Progress [40].

Tobacco use and common chronic conditions

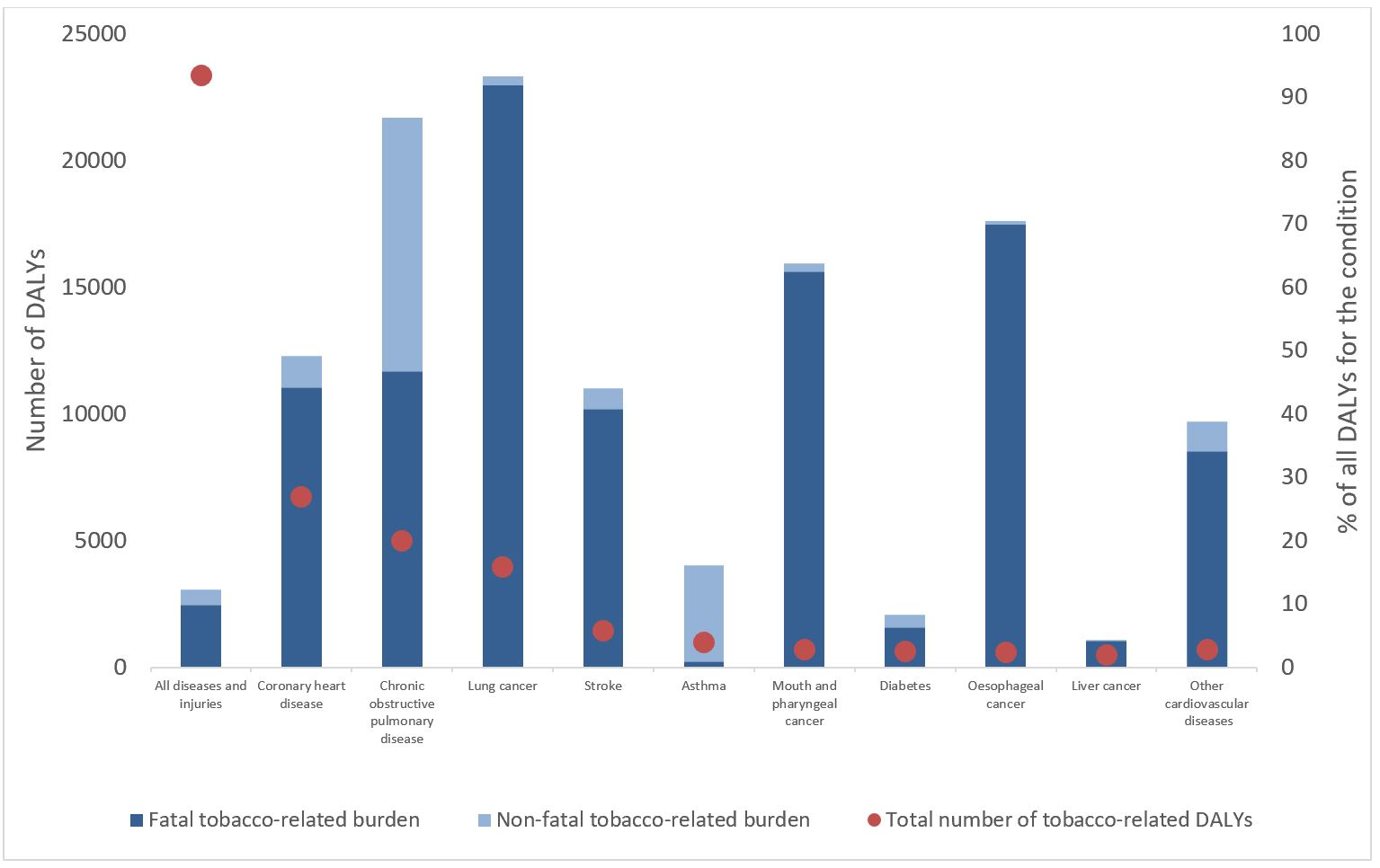

The highest burden of disease from smoking is from atherosclerotic diseases (mainly coronary heart disease (CHD)), cancers, chronic lung disease, and type 2 diabetes (Figure 2) [61]. Smoking is causally linked to a wide range of health conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, tooth and gum disease, pneumonia and hip fractures [40]. The mechanisms by which smoking causes these chronic diseases are summarised below.

Atherosclerotic diseases: coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebrovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease (PAD)

Large international cohort studies, including the Framingham Study, first established the association between smoking and coronary health disease (CHD, also known as ischaemic heart disease), myocardial infarction (MI, heart attack) and mortality in the 1960s [62]. Further studies have identified how smoking contributes to the development of atherosclerosis, the process that underlies development of CHD, most cerebrovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Atherosclerosis results from damage to the lining (endothelium) of arteries, progression to a chronic inflammatory state, and development of fatty endothelial plaques [40]. Over time, these plaques develop a fibrous cap and, together with the formation of blood clots (thrombosis), can lead to local arterial narrowing. Arterial blockage from ruptured plaques and thromboembolism can cause acute cardiovascular events such as MI and stroke.

Cancer

At least 69 of the more than 7,000 chemicals in tobacco smoke are carcinogens (cancer-causing substances) [40]. The body attempts to detoxify these carcinogens via enzymes, which can lead to metabolic activation of reactive compounds that can alter sections of DNA [63]. If not repaired, this altered DNA can result in cell mutations. Combined with carcinogen-related inactivation of tumour‑suppressor genes and receptor-mediated survival of damaged epithelial cells, these mutations lead to the abnormal and uncontrolled cell growth characterised by cancer. The causal relationships between tobacco smoke and many cancers – including lung, head and neck, pancreatic, liver and colorectal cancers – are well established [40]. Smokers with all types of cancer are at increased risk of death compared with non‑smokers [40, 63].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – which includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis and chronic asthma – is characterised by chronic irreversible airflow obstruction. The body mounts an immune response to the prolonged irritation and oxidative stress from tobacco smoke that, over time, can lead to permanent changes to the lungs, including widening of the air sacs, excessive mucous secretion, and stiffening of the smaller airways [40].

Type 2 diabetes and diabetes complications

Cigarette smoking can cause diabetes and the risk of disease increases with intensity of smoking [40]. In particular, nicotine contributes to the development of pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes and the vascular complications of diabetes through three mechanisms:

- decreased sensitivity of body cells to the action of insulin, leading to higher blood glucose levels

- reduced insulin production from pancreatic beta cells, and

- loss of beta cells from prenatal and neonatal exposure to nicotine [64].

Smoking affects the development of the macro-vascular complications of diabetes (atherosclerotic diseases), which are the leading cause of mortality for people with diabetes [65]. However, evidence is limited for the relationship between smoking and the microvascular complications of diabetes: kidney disease (nephropathy), eye disease (retinopathy) and nerve damage (neuropathy).

Evidence indicates that people who already have diabetes who quit smoking:

- reduce their risk of death by around two-thirds

- reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease by over 80%, and

- reduce the risk of stroke to the same as for never-smokers [66].

Smoking in pregnancy

The negative effects of smoking on reproductive health are extensive. The US Surgeon General’s 2014 report summarises that ‘smoking affects the likelihood of pregnancy, the outcome of pregnancy, and the future health of the child’ [40, p.498].

Maternal smoking during pregnancy (and to a lesser extent, exposure of the mother to second-hand smoke) is associated with increased risk of a range of poor birth outcomes, and health effects on the child in infancy and later life [67-71]. These effects may occur through a range of mechanisms, including reduced oxygen delivery to the foetus, imbalances in essential nutrients, DNA changes, and the direct toxic effects of nicotine exposure [63]. Maternal smoking increases the risk of:

- ectopic pregnancy [72]

- spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) [63]

- foetal growth restriction [73]

- preterm delivery [72]

- stillbirth and perinatal mortality, and [74, 75]

- cleft lip and/or palate [76].

A large study of babies born to Aboriginal mothers in NSW found that not smoking in pregnancy reduced the risk of having a baby that was small for gestational age by 65%, and reduced the risk of both perinatal death and preterm birth by 42% [77]. The increased risk of stillbirth and perinatal mortality from maternal smoking probably arise via placenta praevia and placental abruption, preterm delivery, premature and prolonged rupture of the membranes [40].

Maternal smoking during pregnancy is a significant risk factor for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and Sudden Unexpected Death of the Infant (SUDI), via both a direct mechanism and the associated increased risk of pre-term birth and low birthweight [78].

Evidence also exists for links between maternal smoking and later-life outcomes for the child, including Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder [71], obesity [68], asthma under the age of two years [70], and diabetes after age 16 years [69].

Second-hand smoke

Exposure to second-hand smoke is associated with increased risk of a range of conditions, including COPD, CHD, lung cancer, and stroke [40, 70, 79]. Children exposed to second‑hand smoke are at increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease, middle ear disease, lower respiratory infections and asthma [70, 80, 81].

Evidence suggests that people exposed to second-hand smoke are more likely to start smoking, more likely to have a heavier dependence on nicotine, and are less likely to initiate and sustain quit attempts [82].

Third-hand smoke

Third-hand smoke (THS) consists of the nicotine and combustion products of second-hand smoke that persist on dust and surfaces including carpets, blankets, clothes and skin. These can react with other chemicals in the environment to form new toxins – which can take months to years to disintegrate – and can be repeatedly re-suspended, or re-emitted in gaseous form, into the air [83]. Compounds of THS can be inhaled, absorbed through the skin, or ingested, and children are most susceptible to exposure. The health effects of THS have not yet been quantified, but may include harms to the liver, lungs and skin, and behavioural changes [84].

Chewing tobacco and e-cigarettes

Smokeless tobacco products, like chewing tobacco and e-cigarettes, are thought to be less harmful to health than smoking, yet many still contain harmful carcinogens and nicotine similar to commercial tobacco [85]. While the evidence is sparse in Australia for these forms of tobacco use, there is international evidence that chewing tobacco and e-cigarette use are harmful to health.

There is evidence from other populations that chewing tobacco is linked to increased risk of death from all causes, and specifically linked to death from cancers (tongue, lip, gum, cheek, throat, oesophagus and pancreas), and cardiovascular disease [86]. Using chewing tobacco while pregnant is linked to poor birth outcomes (preterm birth, low birth weight, still birth, neonatal nicotine addiction and withdrawal syndrome) [87-89]. As chewing tobacco research has been conducted largely in international settings with different plants, people and contexts of use, these findings may not be generalisable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ use of chewing tobacco [20, 90].

There is international evidence too about the health harms of e-cigarettes. While they are often marketed as being less harmful than smoking cigarettes, there are increasing concerns globally about their health impacts [91]. E-cigarettes have been found to have direct health harms, including increased risk of respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease and carcinogenesis [59, 92]. Further, there is growing evidence that e-cigarette use can be a precursor to smoking (both in young people and in previously non‑smoking adults) [23, 93, 94]. The Cancer Council Australia have issued a statement that, based on the current evidence, the harms of e-cigarettes outweigh the potential benefits [59].

There have also been almost 3,000 cases of lung injuries from e-cigarette use in the United States, leading to hospitalisations and 68 deaths as of February 2020 [95]. While evidence is not yet sufficient to rule out other chemicals of concern, vitamin E acetate has been strongly linked to the outbreak and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) has also been linked to most cases. The number of new cases of lung injury was declining in early 2020.

Tobacco-related disease burden

The burden of disease is the combined impact of living with and dying from diseases, health conditions and injuries. The burden can be measured in years of ‘healthy’ life lost due to ill health, disability and premature death, using Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) [96]. One DALY can be interpreted as one year of healthy life lost. Adding these DALYs up for a population estimates the total burden of disease. It also gives an indication of the gap between the current health situation and an ideal situation where the whole population lives a long life, free of disease and disability.

In 2011, more than 12% of all disease burden in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population was attributed to tobacco use (equivalent to >23,000 DALYs or 23,000 years of healthy life lost) (Figure 2) [61]. This includes the contribution of past and current tobacco use, and exposure to second-hand smoke in the home, but it does not include exposure to smoking in-utero. Most of the total tobacco-related burden was due to CHD (6,747 DALYs); tobacco explains 49% of the total burden of CHD. Tobacco contributes to the majority of the lung cancer (93%) and COPD burden (87%) in the population, but these conditions contribute to fewer DALYs (3,970 and 4,993, respectively) because they are less common in the population.

Lung cancer accounted for 2.4% and 2.2% of total DALYs among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and females, respectively [61]. Results from a 15 year follow-up study with 2,273 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults from remote Far North Qld found a four-fold increase in lung cancers among smokers compared to non-smokers. No participants had cancer at the beginning of this study [97].

The most recent analysis of tobacco-related hospitalisation data from 2007 to 2009 showed that 3.3 hospitalisations per 1,000 in the population were for a tobacco-related diagnosis [98].

Figure 2: Burden of disease attributable to tobacco use as number and percentage of DALYs, by disease, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 2011

Note: The proportion of DALYs attributable to tobacco use has been further divided into fatal and non-fatal burden

Source: AIHW (2016) [61]

Tobacco-related mortality

The 2011 Burden of Disease Study did not estimate the contribution of smoking to deaths in the population [61]. In the 2003 Burden of Disease Study, it was estimated that 20.0% of all deaths were attributed to smoking [99]. A report on the social costs of tobacco in Australia in 2015/16 estimated that at least 886 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander premature deaths are caused by smoking each year [100]. This estimate includes 491 male deaths and 395 female deaths, 82 deaths at age 25-44 years, 441 deaths at age 45-64 years, and 361 deaths at age 65 years and over. Earlier studies, from the 1990s, indirectly estimated the proportion of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths caused by smoking [101, 102], and the potential gains in life expectancy if tobacco-related deaths were avoided [103], using the aetiologic fractions method. All of these estimates of smoking-attributable mortality are based on indirect methods, incorporating evidence from other populations. There is a need for evidence specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples on the relationship between smoking and mortality, and the contribution of smoking to deaths at the national level; this work is underway [104].

Impact on community and culture

Given that tobacco use is the biggest contributor to burden of disease and mortality among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smokers, it has a great impact on the community. The burden of grief that comes with the loss of older generations can have significant impacts on families and communities [105]. Wiradjuri woman, Jenny Munro, speaking about high mortality rates in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities shared:

You get to a point where you can’t take any more and many of our people withdraw from interacting with other members of their community because it’s too heartbreaking to watch the deaths that are happening now in such large numbers… In 227 years we have gone from the healthiest people on the planet to the sickest people on the planet. [106, paragraph 35]

Premature deaths of community members, including Elders and older community members prevents the transmission of generational knowledge, kinship, language, customs and law which are interconnected components of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture [107-109].

Factors related to tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Tobacco use is a complex behaviour, shaped by a range of historical, cultural, community, family and personal factors. It is important to understand the multi-layered factors that have led to high prevalence of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Unless explicitly stated, literature and evidence presented in this section is specific to the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander population.

Tobacco industry

The tobacco industry is responsible for the harms caused by tobacco. In Australia, almost all cigarettes are from three transnational tobacco companies Philip Morris International (PMI), British America Tobacco (BAT), and Imperial Tobacco [110]. Australia no longer grows commercial tobacco or manufactures tobacco products. An estimated 14,062 million cigarettes were sold in Australia in 2017, excluding roll‑your-own tobacco [111]. In January 2019, there were 60 brands and sub‑brands of factory-made cigarettes, including 327 unique variant and pack size combinations on the Australian market [110]. The tobacco industry promotes tobacco sales and consumption and interferes with and opposes tobacco control policies and activities to reduce tobacco use in Australia. The tobacco industry has:

- exploited and appropriated Indigenous names and imagery [32]. Winfield used an image of an Aboriginal man playing the digeridoo to market their cigarettes overseas as ‘Australians’ answer to the peace pipe’ [112, 113]

- targeted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities through advertising. For example, one brand attempted to promote good will through providing funding from the sales of their cigarettes to buy jerseys for local sports teams [27, 112]

- monitored tobacco control research and activities in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities [113]

- obstructed the implementation of public health measures [114], including funding organisations to mislead and distract the public, as well as opposing tobacco control legislation and the FCTC [110], and

- advanced misinformation about the harms of tobacco use [110, 114].

Recently, the tobacco industry has purported to ‘rebrand’ themselves as helping to reduce the harms caused by tobacco use [110]. For example, PMI has sent letters to Aboriginal organisations promoting its e-cigarettes as a tobacco control measure [115]. PMI also provided US$1 billion in funding to establish the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World [116]. The Foundation’s mission is to ‘end smoking in this generation’, and has specifically targeted Indigenous peoples with its funding of the Centre of Research Excellence: Indigenous Sovereignty & Smoking in Auckland [32, 116]. BAT has also stated that its work aligns with the United Nations Strategic Development Goals in an attempt to establish its corporate social responsibility [110, 117]. Despite these attempts at changing their public-facing agenda, to be genuinely socially responsible, the tobacco industry would have to cease the sale of tobacco and their opposition to tobacco control [32, 110, 114, 118].

There is a proud history of examples of Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples and organisations resisting offensive tobacco industry marketing of its products, and many Indigenous leaders have opposed this latest tobacco industry initiative [32, 113].

Governments, health services and individuals need to understand how tobacco industry tactics are used to undermine public health efforts. The Australian Government has a responsibility as a signatory to the FCTC to protect public health policies from the vested interests of the tobacco industry [11]. The misinformation, promotion and targeted advertising can erode self-determination.

Ongoing impacts of colonisation

As noted earlier, colonial processes have directly led to tobacco use and addiction among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [27, 28, 30, 36]. In addition to these direct pathways, there are profound ongoing impacts of colonisation and subsequent government policies that contribute to the use of tobacco today. For example, colonial processes have contributed – and continue to contribute to – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples disproportionately experiencing barriers to employment, poverty, higher disease burden, intergenerational trauma, discrimination [7]. These factors, in turn, are associated with smoking and/or are barriers to quitting [31]. Given the complex negative impact colonisation has had on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health through generations, colonisation is considered a social determinant of health for Indigenous peoples [6, 119, 120]. However, there is a dearth of studies that specifically explore the impacts of colonisation on tobacco use [121]. The available evidence is outlined below.

Trauma

Colonialism and subsequent government policies have caused extensive and ongoing trauma [7]. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been removed from their lands, their families and culture [31]. These processes occurred historically, but also continue today, such as through contemporary child removal and incarceration. The trauma from these experiences impacts health and other outcomes across generations [120, 122]. Trauma is linked to a range of outcomes, including substance use and poorer social and emotional wellbeing, which, in turn, are associated with higher tobacco use [31, 123].

Stolen generations and contemporary removal of children from families

The removal of children from their families is linked with smoking. The evidence shows that:

- people removed from their families during the Stolen Generations were more likely to be a current smoker (50%) than those who were not removed (40%) [122], and

- contemporary removal of children also increases the likelihood of smoking. Those aged 15 to 39 years who were removed from their family were more likely to be current daily smokers (66%) than those who were not removed (45%) [124].

Social and emotional wellbeing

The evidence shows that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience a disproportionate burden of poor mental health and/or poor social and emotional wellbeing [125]. Social and emotional wellbeing is linked to tobacco use.

- Analysis from baseline data (collected 2006–08) of a longitudinal study of Aboriginal adults aged 45 years and over in NSW found that the risk of smoking was significantly lower among those with low or moderate levels of psychological distress compared to those with high or very high distress [126].

- Analysis of the 2014–15 NATSISS found that people with a mental health condition were more likely to be a daily smoker (46%), compared with those without a mental health condition (33%) [127].

- Having a mental health condition can be a reason people continue to smoke. Young people have reported smoking to cope with their depression [128].

- Having a mental health condition can make it harder to quit. Those with mental health conditions have lower levels of access to quit services. Further, though they make similar numbers of quit attempts to those without a mental health condition, they are less likely to maintain a quit attempt [129].

Exposure to racism

Colonialism and government policies have embedded racism within systems (structural racism) and within individuals (interpersonal and internalised racism). As a result, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have commonly experienced both kinds of racism [49, 130]. Much less is known about internalised racism and how it links to health and health behaviours. However, it is well established that experiences of racism lead to negative health and wellbeing outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [130, 131].

Racism has been linked with smoking behaviour [123, 125, 130, 132].

- Racism, stereotyping and stigma from media and government interventions contribute to stress that people then attempt to ameliorate by smoking [123].

- Racism has also been linked to early experimentation with tobacco. Analysis of data from the Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) dataset found that young people (10–12 years) were seven times more likely to have tried smoking if they had experienced racism between the ages of 4 and 11 years, compared with those who had not experienced racism [131].

- The TATS study found that people who said they had been treated unfairly in the past year because they were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander were less likely to have made a quit attempt in the past year or have ever made a quit attempt; however, these smokers who had reported racism in the previous year were no more or less likely to quit or sustain a quit attempt in the subsequent year [133, 134].

Exclusion from economic structures

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are significantly more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to be excluded from economic opportunity. This is evidenced by lower incomes, higher levels of unstable housing and/or higher levels of unstable employment, and lower levels of formal education [125]. Conversely, relative advantage across these social determinant indicators is linked to non-smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults [122, 126, 135, 136].

- A study in 2015 in the ACT found that people who completed Year 12 were more than 21 times more likely to be non-smokers than those who did not [137].

- Analysis of the TATS study data found that positive changes in socio-economic factors, such as getting a job or buying a home, have also been associated with sustaining smoking abstinence. However, baseline measures of socio-economic advantage were not significantly associated with starting or sustaining a quit attempt in the next year [138].

- A qualitative study in Qld found that narratives of empowerment and a greater sense of control contribute to sustained cessation [139].

It is important to highlight that many people who do experience socio-economic disadvantage are able to quit smoking or stay never-smokers. Socio-economic disadvantage need not be seen as an insurmountable obstacle to quitting, but there remain many other reasons to address these socio‑economic factors [138].

Incarceration

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are severely over-represented in prisons, making up 28% of the adult prison population and 59% of in youth detention in 2018 [140, 141].

The evidence shows that people who have been incarcerated, detained, or arrested are more likely to be smokers.

- In 2018, 80% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who entered prison reported that they were current smokers at the time they entered [142].

- In 2015, 90% of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in detention in NSW had smoked, and 81% were daily smokers prior to being placed in detention [143].

- Those who had not been arrested or incarcerated within the last five years were, respectively, 4.5 and 4 times more likely to be non-smokers than those who had been arrested or incarcerated [135].

Though smoking is banned in prisons in all states and territories except WA [125], many people who have been incarcerated resume smoking when they leave prison [142].

Substance use

The evidence shows that both alcohol and cannabis use is linked with tobacco use.

- Not consuming alcohol is linked to lower likelihood of smoking. Analysis of the 2002 NATSISS data found that people who had not consumed alcohol in the last 12 months were significantly more likely to be a non-smoker compared to those who had consumed alcohol [135].

- Increased or risky alcohol intake is associated with higher likelihood of smoking.

- A study of older adults in NSW from 2006–08 found that people who consumed no, or low levels of alcohol (1–14 standard drinks per week) were significantly less likely to smoke than people who drank more than 14 standard drinks a week [126].

- Analysis of the 2008 NATSISS found that people who reported risky (short and long term) drinking, chronic alcohol consumption were more likely to be current daily smokers than people who drank at low-risk levels [144, 145].

- Risky drinking impacts quitting. Analysis of the TATS study data found that people who report risky drinking were less likely to want to quit [146] and less likely to make a quit attempt [147] than those who did not.

- The use of cannabis has also been linked with tobacco use; however, the direction of the association is not clear.

- Analysis of 2008 NATSISS data found that current daily smokers were more likely to have used illicit substances such as cannabis, than those who have never smoked [144, 145].

- An analysis of the 2012–13 NATSIHS and the TATS study data found that cannabis use was common (32% and 24% respectively) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smokers [148].

- In the NATSIHS, smokers were almost five times as likely to have used cannabis in the last 12 months than non-smokers [148].

- Further, in the TATS study, 24% of smokers, smoked something other than tobacco (e.g. cannabis), and that 92% of these people reported mixing tobacco and cannabis together to smoke [148].

Using one substance (tobacco, cannabis or alcohol) significantly increased the likelihood of using the other substances. A survey of substance use with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women during pregnancy found that among women reporting current substance use, 56% reported using one substance only and 44% reported using two or three [149].

Stress

On average, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience high levels of stress, resulting from colonisation and its ongoing impacts [7]. Evidence indicates that stress is related to smoking [49, 135, 150, 151]. Moreover, experiencing multiple life stressors (such as a serious illness, death of a family member, violence, relationship problems) is associated with increased levels of smoking compared to experiencing no life stressors [135].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that a key reason for starting and continuing smoking is for stress management [31, 50, 123, 139, 152]. Smoking has been described as a way of taking a moment to oneself to relax and de-stress [35]. However, much of the stress relief from smoking may be because smoking another cigarette relieves the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal [129].

Smoking’s role in stress management means that high levels of stress can be a barrier to quitting and maintaining quit attempts [151]. Indeed, stress arising from life crises, such as a death in the family, have been reported as causing increased smoking intensity and relapse after a quit attempt [35, 153, 154].

However, the TATS study has shown that higher baseline stress predicted quitting smoking and maintaining a quit attempt for at least a month [147]. Particular forms of stress – such as stress about the health impacts of smoking, financial stress caused by spending on tobacco, and stress related to the stigma of smoking – may actually support people to quit smoking [139, 147, 155]. It may be that stress can motivate people to improve both their health and their financial situation through quitting smoking. This is important because, while we know stress is a key reason for why people do smoke, it may not be an insurmountable barrier to quitting.

Financial stress

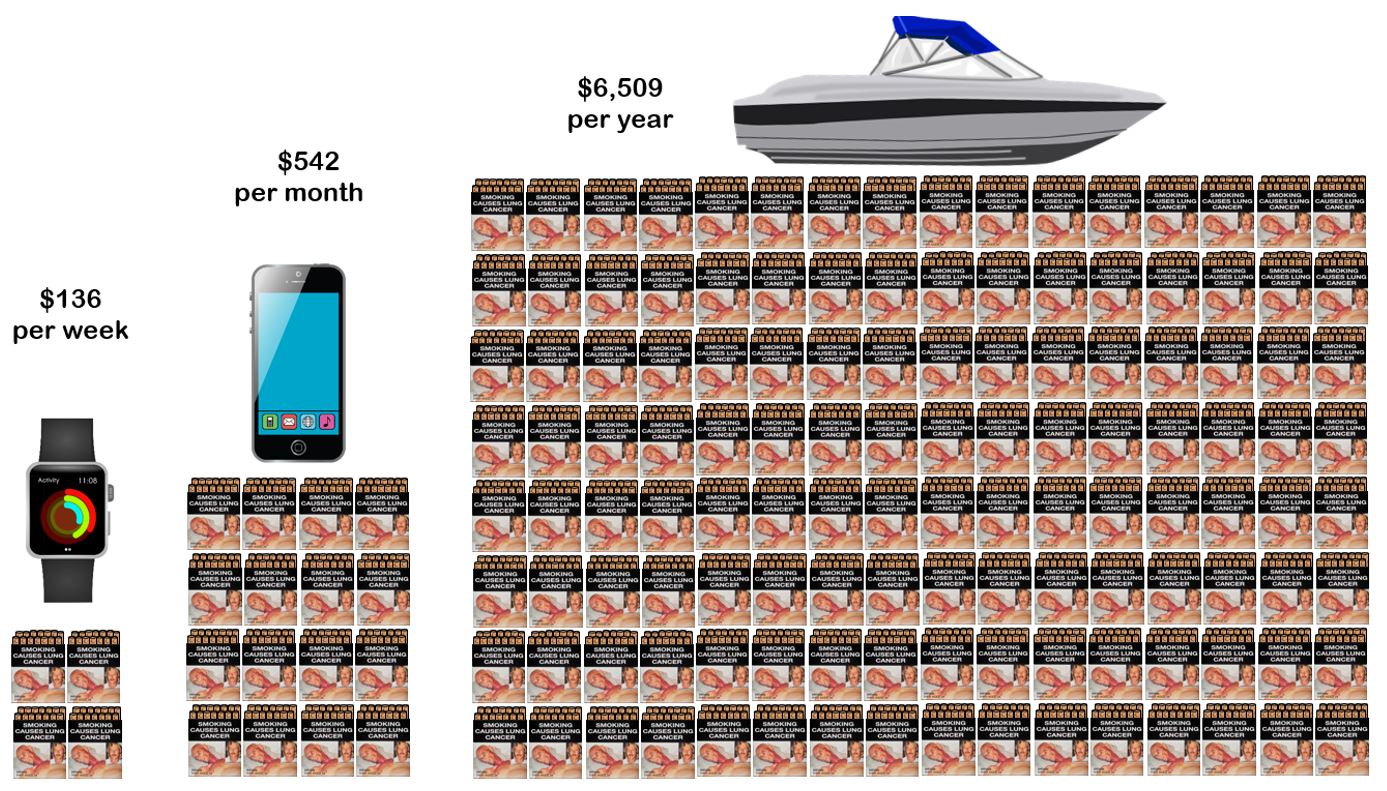

Financial strain is one form of stress that is closely linked with smoking. People may use smoking as a mechanism to cope with financial strain; however, the cost of smoking, in turn, can increase financial strain. Smoking can be expensive. In 2019, the average price of a 25 packet of cigarettes was $33.90 [156]. According to the National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016, the mean number of cigarettes smoked per week by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 18 years and over who smoke was 95.8 or approximately four packs (based on a 24 pack of cigarettes) [157]. Therefore, the average Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult who smokes will spend $136 per week, $542 per month or $6,509 per year on cigarettes [56]. Figure 3 shows an example of what the money could be spent on if someone were to quit smoking.

Figure 3: Money saved if an average smoker quit smoking, 2017

Source: Derived from AIHW data (2017) [56]

Normalisation of smoking

Due to high prevalence, some communities and families see tobacco use as the norm [108]. Perceived norms around smoking can be an important factor influencing tobacco use attitudes and behaviours [31, 158]. For example:

- viewing adults smoking in the household or community can lead young people to see smoking as a normal part of being an adult [128].

- smoking behaviour among family and friends can be influential in smoking initiation for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [152]. A 2015 study in the ACT found that the likelihood of smoking increases as the proportion of people in a household who smoke increases [137].

- smoking behaviour of friendship groups also plays a large role in young people beginning to smoke [31].

- youth are less likely to smoke if they perceive it as socially unacceptable, and if family and friends do not smoke [152].

Studies have demonstrated that in contexts where smoking is normalised, smoking can have positive impacts on social relationships. Tobacco use has been found to:

- be an effective mechanism to maintain and strengthen kinship and social relationships, and promote belonging and social cohesion [159], and

- provide a sense of community, belonging and connection [160].

Social role of smoking

Smoking can play a social function, potentially fostering an environment that can lead to the continuation of smoking and acting as a barrier to quitting [152, 161]. Smoking and sharing cigarettes have been viewed as ways of maintaining and strengthening relationships by Aboriginal youth in urban NT [162]. The maintenance of relationships is a high priority in many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, often given precedence over individual wishes [31]. In this context, obligations to share resources, and to provide and receive gifts is a vital part of social life [14]. Gifts of tobacco have been described as a key way of partaking in reciprocal exchange, an expected part of relationships, and a way of showing care, love and respect [14, 21, 31].

For example, Aboriginal Health Workers (AHWs) in South Australia (SA) reported that smoking provides an opportunity to socialise with co-workers and facilitates relationships with community members [35]. Other people have reported smoking to gain entry into a particular social group, or as a way of having important conversations with peers who smoke [152]. Smoking can also provide a source of identity, status and a sense of belonging to a certain group [31, 35].

Factors in the initiation of tobacco use

Initiation occurs most commonly when people are young (see Smoking initiation for more information) [43].

It is important to note that initiating smoking, or indeed choosing not to smoke, is not a one-off event but rather a complex pattern of behaviour that varies from person-to-person [163]. For some people, initiation occurs in stages, for example: first try and experimentation, social or casual smoking and then established smoking [162]. Though, not all people who experiment or socially smoke will become established smokers.

The influence of family and friends is a major factor in the initiation of smoking by young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [121, 162]. Specifically, family and friends who smoke increase the accessibility of tobacco products, and social desirability of smoking and influence the normative attitudes towards tobacco use.

- Young people have reported sourcing their first cigarettes from family members (with and without permission or approval) [162].

- Young people have also reported that progression to social and established smoking was influenced by smoking behaviours in their broader social networks [162].

- Almost 60% of people from a 2015 study in the ACT reported that a friend or acquaintance gave them their first cigarette [137].

- Smoking is also reported as a behaviour people do to gain ‘cool’ status, to seem older, to assert their membership to the group and to live their Aboriginal identities. This internalisation of smoking as a way of being Aboriginal may have resulted from the high prevalence of smoking in these rural coastal communities. For them, smoking was a way to be like others, socialise and belong to a group [31].

The large role that the smoking behaviour of others plays in an individual’s initiation of smoking highlights the importance of addressing smoking behaviour at the community level, as well as working with young people to not start smoking [121].

Quitting

Evidence shows that smokers want to quit [133, 164]. The TATS study found that 70% of people who smoke daily want to quit, 69% of people who smoke daily had ever made a quit attempt, and 48% had made a quit attempt in the past year [164]. However, it also found that only 30% of people who tried to quit in the past year sustained the quit attempt for longer than one month [133].

Evidence also shows that quit attempts are increasing. The percentage of people who smoke who attempted to quit increased from 45% in 2008 to 50% in 2014–15 [43]. Females were more likely to attempt to quit compared to males (54% compared to 47%) and those living in remote areas were more likely to attempt compared to non-remote daily smokers (58% compared to 48%).

Successful quit attempts are also increasing. In 2014–15, 36% of adults who had ever smoked had a successful quit attempt [43]. This is an increase of 12 percentage points from 2002 (24%). The percentage of successful quit attempts was similar among males (34%) and females (37%) and higher in non‑remote areas (39%) compared to remote areas (24%). These findings suggest that despite more quit attempts being made by remote daily smokers, the success rate of these quit attempts is lower than for their non-remote counterparts.

Factors related to quitting

Knowledge about the health effects of tobacco

Direct health impacts

While knowledge on its own is not enough, knowledge of the direct health effects of smoking can be influential in changing smoking behaviour. Concern about these effects is reported as a reason why some people do not initiate smoking and is associated with wanting to quit and making quit attempts [134, 152, 165]. Analysis of the TATS study found that concern for personal health was the most common reason for making a quit attempt, with 93% of smokers citing it as a reason for making a quit attempt in the last six months [134].

Health messaging seems to be particularly effective when it aligns with resonating personal experience. Participants in studies in NSW and SA reported that experiencing smoking‑related health complications, or knowing someone who had, made them want to quit [50, 51]. Another salient concern for some people was the impact of smoking on their fitness and ability to participate in sporting activities [51, 152]. Analysis of the 2014–15 NATSISS data found that 40% of people who tried to quit or reduced their smoking reported improving their fitness as a motivation factor [150].

Impacts of tobacco use during pregnancy

For many women, pregnancy motivates a change in tobacco use [151, 166]. The National Perinatal Data Collection showed that, in 2017, 12% of women who smoked in the first 20 weeks or pregnancy had quit in the second 20 weeks [167]. A 2012 study of pregnant women in NT and NSW found that, of those who were smoking prior to their pregnancy, most (68%) took a step towards quitting, with one in five (21%) quitting and almost half (47%) reducing tobacco use during their pregnancy. Those who did, were found to have a better understanding of the smoking-related risks including miscarriage, low birth weight, infant illness and child behavioural problems, than those who continued smoking [168]. This finding shows that knowledge of the health effects of smoking during pregnancy is a motivator for behavioural change to quit smoking. A 2018 qualitative study with Aboriginal women from Qld, NSW and SA found that, while participants understood smoking was harmful they reported wanting more information to better understand the impacts of smoking during pregnancy [169]. This finding shows that there are still improvements in communicating the health impacts of smoking during pregnancy which is particularly important given the role health knowledge plays in quitting smoking.

Impacts of second-hand smoke exposure

Research has also demonstrated that health information focusing on the indirect health impacts on others can be particularly influential in changing smoking behaviour. Concern for others and the importance of family wellbeing and protecting family members from the negative impacts of smoking can be a key motivator for people to quit smoking [14]. Further, findings indicate that the impact of smoking on others is more influential than the direct effects on the person who smokes. High levels of knowledge of the harmful effects of second-hand smoke is linked with health worry, wanting to quit and making quit attempts, even though knowledge of the direct health impacts alone was not linked with these outcomes [165]. Another study found that 75% of people who made quit attempts reported concern for the effect of cigarette smoke on non-smokers as a reason for quitting [134].

Individuals, organisations, and communities have demonstrated strong support for smoke-free homes and cars. Supporters of these policies are more likely to be non-smokers, compared to people who do not support them [50, 52, 136, 170].

Community factors

Denormalisation

Decreases in smoking prevalence contribute to a denormalisation of tobacco use in communities [171]. Denormalisation of smoking sees a change in the social norms of smoking and a push towards smoking being perceived as an undesirable activity. Community attitudes can influence tobacco use. For example, people who felt that the community leaders where they live disapproved of smoking were almost twice as likely to want to quit than those who did not have that perception [146].

While the denormalisation of smoking can be beneficial in further encouraging smoking cessation and non-initiation, it can also negatively impact on the wellbeing of people who feel stigmatised for continuing to smoke. For many women, tobacco use, even during pregnancy has often been perceived as a socially acceptable response to stress [108]. However, with changing attitudes towards smoking, people who smoke are increasingly concerned about being judged for smoking. A systematic review and thematic synthesis of several studies involving Indigenous women from Australia and New Zealand found that many women wanting to quit felt shame and guilt for their behaviour and concern about stigmatisation. Consequently, these women hid their smoking behaviour to avoid judgement [160].

In addition, studies have found that general practitioners (GPs) and midwives, recognising this fear of judgement, are reluctant to discuss the consequences of smoking with pregnant women as it may be damaging to their relationship [172]. A key informant from Central Australia stated that young pituri users will re-position a quid in their mouths to obscure its presence to avoid feeling ashamed [21]. People who smoke have reported that it is harder for people to smoke nowadays and that they feel the need to smoke in secrecy, together with feelings of guilt for smoking [51]. The TATS study found that 70% of people who smoked daily strongly agreed or agreed that there are fewer and fewer places where they felt comfortable smoking [173].

Family and friends

Given the social role of smoking, the support of family and friends is vital in supporting quit attempts. The evidence shows that people who smoke and who have support from family and friends to quit, make a quit attempt and sustain the quit attempt for at least a month, compared with those who do not have that support [174].

Reports of tobacco use among family, friends and co-workers can discourage quit attempts and make it harder to successfully quit. For someone attempting to quit, the presence of other people smoking and of tobacco creates constant thoughts about smoking. Living in a household with another person who smokes is associated with the maintenance of smoking, including for pregnant women who want to quit [152]. Additionally, people who live with other adults who smoke and people whose five closest friends all smoke are both less likely to make a quit attempt over time [174].

A salient concern commonly reported is that those who choose not to smoke or have quit smoking may risk social isolation [31, 50, 152, 160].

- The TATS study found that over a quarter (27%) of people who smoke daily said that they believed non‑smokers missed out on all the good gossip/yarning [173].

- A 2012 study with SA AHWs found that AHWs feel a need to smoke to facilitate socialisation and connection to community or clients. They feel a social pressure to smoke and fear social exclusion if they were to quit [154].

Role modelling

Many adults have described wanting to be a role model as a key factor in deciding not to smoke, or to quit smoking [14, 134]. Evidence suggests that role models can champion and facilitate smoke free norms [137]. Non-smoking role models have also been found to be influential in preventing smoking initiation [128].

- The TATS study found that 90% of people who smoked daily either agreed or strongly agreed that being a non-smoker sets a good example to children [173].

- It also found that four in every five people who smoke or smoked in the past reported setting an example for children as a reason for thinking about quitting, making quit attempts and helping them to stay quit [134].

- Further, a 2016 study with people from SA, found that both men and women reported changing their smoking behaviour to be good role models to their children to improve their children’s future health outcomes [51].

- In SA and East Arnhem Land in the NT, AHWs have also reported wanting to be good role models for their clients [35, 175]. They explained that quitting smoking would help them advise and help their clients, and keeping smoking would negatively impact their relationships with clients and effectiveness of their messaging.

What is linked with wanting to quit?

Analysis of the TATS study highlights personal attitudes and factors that are linked to individuals wanting to quit smoking. They include:

- Regretting starting

- People who regretted ever starting to smoke were almost three times more likely to want to quit than those who did not have such regrets [146].

- People who agreed that if they had their time again they would not have started smoking have also been found to be more than twice as likely to have made a quit attempt between baseline and follow-up surveys [134].

- Perceived benefits from quitting

- People who perceived high levels of benefits from quitting smoking were almost four and a half times more likely to want to quit than those who did not have such perceptions [146].

- The study also showed that recent quitters had positive attitudes about quitting. Of people who recently quit, 87% said they have more money since they quit, 74% said they cope with stress as well as when they were smoking, and 90% said their life is better now they no longer smoke [161].

- Having lots of worries

- People who reported often having too many worries to deal with were two and a half times more likely to want to quit than those who reported not having too many worries [146].

- Spending too much money on cigarettes

- Eighty-one percent of people who smoke daily reported spending too much money on cigarettes. People who reported spending too much money on cigarettes were more than two times as likely to want to quit and almost one and a half times as likely to have attempted to quit in the last year [161].

- This finding is supported in an analysis of the 2014–15 NATSISS data which found that 59% of people who tried to quit or reduce their smoking reported cost as one of the reasons for doing so [150].

What is linked with not wanting to quit?

In contrast, there are several attitudes that can contribute to people not wanting to stop using tobacco. These include enjoying smoking and believing it is very difficult to quit smoking. Analysis of the TATS study found that people who held these attitudes were less likely to want to quit than those who did not report these attitudes [146].

Some other attitudes that have been reported as contributing to not wanting to quit. These include:

- believing there is no point in their quitting smoking when they were exposed to high levels of second-hand smoke from family and friends who smoke [152]

- believing quitting smoking is not their highest health priority in the context of complex health concerns, such as weight management related to diabetes or heart disease [35, 139, 152], or alcohol or other drug use [152]

- maintaining a fatalistic view of their ill-health, believing that their health was outside of their control [139, 165]

- not trusting, valuing or respecting information about quitting because they:

National policies and strategies impacting tobacco use