The ‘Good Quick Tukka’ cooking program, ‘Cook it, Plate it, and Eat it’

Brief reportSuggested citation: Chen D. (2019) The ‘Good Quick Tukka’ cooking program, ‘Cook it, Plate it, and Eat it’. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 19(3).

Corresponding author: Debbie Chen, email: deb.chen@yahoo.com

For more information: https://www.qaihc.com.au

Download PDF (435KB)

Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of Good Quick Tukka (GQT) is to increase consumption of home cooked meals and to increase cooking skills among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Objectives include:

- increasing confidence and skills required to prepare food and cook healthy meals

- identifying enablers for cooking for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- identifying barriers and enablers to implementing GQT.

Methods

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from participants and facilitators through surveys, and interviews conducted 6 months after completion of GQT. Facilitators were interviewed via face to face or written surveys to provide feedback on how to improve GQT. Qualitative data was analysed by extracting the common themes.

Results

Participants are using skills learnt from GQT, 73% were cooking the recipes at home and 27% stated they were cooking more often. Enablers to cooking at home included quick meals and increasing skills and knowledge. Enablers to implementing GQT include students demonstrating GQT at community events, target existing groups and combine GQT with health checks. Barriers included lack of management support and budget constraints.

Conclusions:

GQT improved people’s confidence in cooking and changing their behaviour. It is a program that can be expanded with more effective evaluation processes to capture data.

Implications:

GQT is an effective strategy to increase cooking skills, confidence and knowledge for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It may be useful to target youth and people who don’t know how to cook with a focus on a ‘hands on approach’ rather than cooking demonstrations.

Background

Good nutrition early in life and throughout the lifespan is recognised as being important in the prevention of chronic diseases. The prevalence of chronic disease such as Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is significantly higher than that of non-Indigenous Australians with Type 2 diabetes at a rate that is 3 times higher (1).

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the recommended daily intake for fruit and vegetable is not being met with people living in remote communities self-reporting less fruit and vegetable intakes than non-remote areas (2). For urbanised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, high food costs, poor access to healthy foods/convenience for takeaway foods, budgeting, poor nutrition knowledge and limited cooking skills were all barriers to healthy eating and food insecurity (3).

Households buying fewer vegetables report less confidence in cooking (4) which may suggest that people do not have the time, skills or knowledge to incorporate fruit and vegetables into cooking meals at home. These insufficient levels of fruit and vegetable intake contribute to 4% of the total burden of disease and injury for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (5).

Strategies that have been used to reduce the prevalence and incidence of nutrition related chronic diseases include cooking classes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that have proven to be effective for improving cooking skills (6, 7). Other benefits include increased confidence in cooking particularly if participants are involved in the cooking rather than a cooking demonstration. Although cooking skills are important, food preferences, family influences and cooking equipment also impact on cooking at home (8). It is acknowledged that a cooking program alone will not improve nutritional status without addressing other issues such as lack of access to healthy foods, inadequate housing, and other socioeconomic factors that impact on health. There are still limited data in relation to food preparation amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, which can be improved.

The Good Quick Tukka (GQT) program uses the framework of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion for the development of GQT. It focuses on developing personal skills, yet other factors such as strengthening commun

ity action and reorientating health services are all key factors in engaging with the local communities. Community ownership is a key factor, recognising that dealing with one barrier to dietary change is unlikely to have much influence on lifelong dietary behaviours or structural barriers to change. However, it may be a useful starting point for initiating dietary change which may in turn lead to enhancing community capacity and increasing self-esteem of participants (9).

Implementation

The philosophy of GQT requires all GQT recipes to include either fruit or vegetables, be low in saturated fat and sugars, budget friendly and to be cooked and plated within 30 minutes. The program also utilises a ‘Pass on’ concept which encourages participants to pass on the cooking skills, knowledge and recipes that they had acquired as part of the GQT program to colleagues, family, friends and the community.

Following the demonstration to Health Workers by the Nutritionist, GQT was incorporated into a range of existing programs including lifestyle programs, diabetes sessions or family groups. GQT sessions were also implemented specifically for staff. Recipe books and cooking utensils were used as incentives in efforts to encourage further participation in GQT programs and in cooking recipes at home. It is hoped the skills learnt or developed will be transferred into the home environment so people increase the amount of meals being prepared which incorporate vegetables and fruit.

The overall aim of GQT is to increase consumption of home cooked meals and to increase cooking skills among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The objectives for GQT are:

- engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, young people and adults

- increase confidence and skills required to prepare food and cook healthy meals

- enhance and explore cooking techniques and experiences focusing on the social fun and enjoyment of food

- identify enablers for cooking for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- identify barriers and enablers to implementing GQT.

The program was initially implemented in 5 Community Controlled Health Services located in South East Queensland and the data were collated from 62 sessions over a period of 2 years.

Evaluation

To measure the aims and objectives, a mix of qualitative and quantitative data were collected from participants and facilitators through surveys and group interviews with the qualitative data analysed by extracting the common themes. At each GQT session all participants completed an evaluation form which included demographics, their self-rated cooking skill level, the number of home cooked meals prepared each week, the amount of soft drinks and take away foods consumed the previous day and enablers to cooking at home. Facilitators collated comments from participants at each session.

Two group interviews for participants were conducted approximately 6 months after completion of GQT programs in two different regions; qualitative data were collected on changes in behaviour regarding cooking, eating habits and how to improve GQT as a program. Facilitators were also interviewed via face-to-face or written surveys to provide feedback on how to improve GQT.

Results

Results were collated from 62 GQT sessions with an average of seven participants per session. Participants ranged from teenagers to people aged 70 plus and over 60% of respondents identified as an Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander person.

1) Participants’ results for confidence in cooking and self-reported behaviours

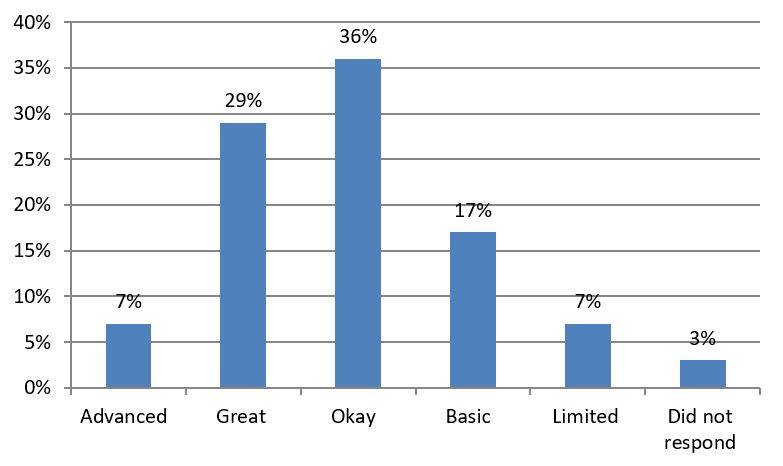

From participants attending GQT, 36% stated that their cooking skills were great or advanced, hence the participants already had competent cooking skills, however one facilitator stated that although the participant scored “Great’ for cooking skills, they observed that the skills across the cooking skill spectrum was basic, hence this can be a subjective ranking. Participants’ self rating of confidence for cooking skills can be seen in Graph 1.

Graph 1: Participants’ self-rating of confidence for cooking skills

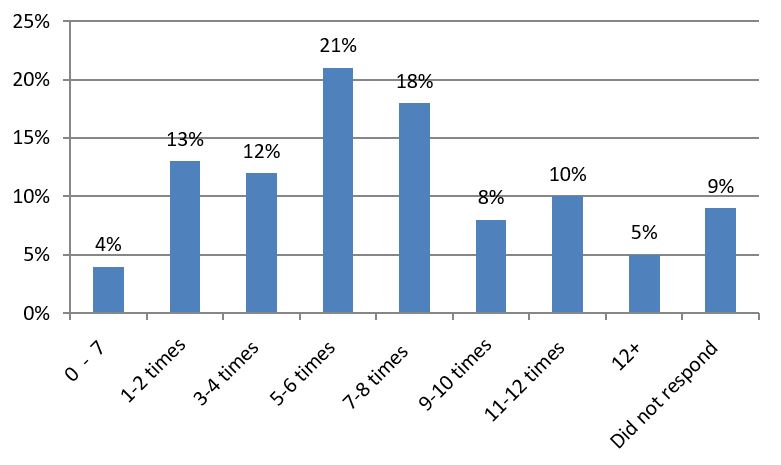

Participants attending GQT varied in the number of times they cooked at home as seen in Graph 2.

Participants attending GQT varied in the number of times they cooked at home as seen in Graph 2.

Graph 2: Participants’ response to ‘The number of times meals are prepared at home per week’

Regarding their intake of takeaway foods and sugary drinks the day before, 33% had consumed sugary drinks and 21% had bought takeaway foods. From the data obtained from the group interviews, 73% of the participants interviewed were cooking the recipes at home and 27% stated they were cooking more often at home. Participants have increased their confidence and self-esteem in cooking, one teenager took a photo as ‘her mum won’t believe that she was cooking’ and an unexpected outcome was that one participant was able to obtain a part time job in a kitchen. Participants were using the skills learnt from GQT that included grilling, steaming, knife skills, and low fat cooking. They were exposed to more variety of tastes with the use of different herbs and spices, and ingredients such as legumes and wholemeal flour.

Since attending GQT, some participants have improved their eating habits such as choosing low glycaemic index carbohydrates and lowering their fat intake. One participant had lost weight and was ‘feeling more active and lively’ and another had ‘much better diabetes control through making healthier choices’.

Of concern was that fruit and vegetable intake did not significantly increase, however some individuals had either decreased their takeaway foods or were making healthier options when buying takeaway foods.

It was difficult to assess the immediate impact of the program on participants’ improvements in confidence or behaviour after a GQT session. However, from the group interviews the impact of GQT has been sustained months later with GQT recipes being cooked at home or used as a base for recipes.

2) Enablers to cooking at home as identified by participants

Participants were asked to identify the factors that would support their ability to cook meals at home. Nine key themes emerged as outlined in Table 1 with the strongest response being quick or fast meals to prepare, followed by increased skills and knowledge.

Table 1: Cooking themes and comments

| Theme | Qualitative comments |

| Quick or fast meals to prepare | · More time

· Quick recipes like these |

| Increased skills and knowledge | · Learning how

· More confidence in preparation |

| Combined effort within the household | · Family chip in

· Help in washing up and food preparation |

| More suitable and available house hardware and space | · More cooking equipment

· Microwave, bigger kitchen |

| Increased or improved planning for meal preparation | · Making a plan of what to cook so I don’t have to think

· Better preparation |

| Someone else to cook | |

| Affordability [of food] | · Knowing where the cheapest place for food and vegies

· Cheaper foods from market, especially vegetables |

| Other | · If Mum trusted me to cook |

| Ingredients available at home |

3) Feedback regarding the challenges and how to improve GQT for the future.

Challenges raised by some facilitators included that participants relied on staff to do the cooking with more cooking demonstrations than actual cooking by staff. Additionally, staff turnover impacted the program as GQT did not continue once a staff member left as no one was aware of how or what GQT was. This led to a lack of momentum for the program to continue. The success of the program was also more evident in centres where there was a champion driver who implemented the program.

Some of the barriers identified by facilitators were that support for staff was limited and there were budget constraints for staff in clinical roles. These barriers highlight that management support is important for GQT to be implemented within the services. Budget constraints could also be minimised with collaboration from other stakeholders and to explore other options such as community gardens.

Enablers to implementing GQT included the following suggestions from facilitators: high school students could be encouraged to do more GQT demonstrations at community events; existing groups be targeted; GQT could be combined with health checks and more marketing to increase access to GQT. Other suggestions included mums and bubs groups cooking the same foods at all feeding stages with discussion on introducing solids, and implementing GQT at playgroups. Sessions could also alternate with recipes one week and skill development the following week. For example, filleting meat, with young mums being a priority.

More discussion regarding nutrition and other topics were requested by participants and facilitators. These included: more low calorie desserts, more salads ‘as I don’t enjoy them’, other cooking methods, portion control, physical activity, self-esteem that trigger poor diets, more sessions and time to include yarning on topics and shopping tours.

4) The ‘Pass On’ concept

The ‘Pass on’ concept has had some participants passing on recipes and cooking at home with one participant passing the recipe on 5 to 6 times the recipes that she has learnt, ‘We are taking it into the family home’. Although there was verbal feedback of passing on recipes at home during the GQT program, there was no evidence of this. Encouragement by facilitators was required to pass on the recipes at home and the use of incentives met with limited success.

The development of the GQT Facilitator Manual

Based on the feedback from staff and participants and in consultation with 13 of our Aboriginal and Islander Community Controlled Health Services, a GQT manual has been developed. It focuses on GQT being ‘practical hands with the emphasis on cooking skills. GQT has also expanded to include an information session facilitated by the QAIHC Nutrition Coordinator that can be provided to staff interested in facilitating GQT programs. A regular newsletter is distributed as requested by facilitators for ‘Greater support, as Health workers need to be skilled up to incorporate it into other programs’.

From the enablers for cooking that were identified, it confirms that the GQT recipe criteria meet the needs of participants. Recipes that are quick, easy and budget friendly are the foundations to encourage clients to cook at home as it can be more difficult to encourage non-cooks to cook if recipes take too long to prepare and they are time poor.

Participants’ comments suggested they had the opportunity to experience different flavours and tastes that they would not normally be exposed to. Although the GQT program is guided by what participants want to cook, the GQT manual includes recipes and highlights recipes that use unfamiliar ingredients or new cooking techniques for groups to try, as it is unlikely that the group would choose a lentil soup to cook in preference to a pumpkin soup. The introduction of using different ingredients and foods within classes also provides opportunities for participants to experiment without the risk of wasting money on foods the family would not eat or being criticised by the family. Participants can gain confidence in using unfamiliar foods that can lead to potential behaviour changes within the home (8).

All evaluation forms have been redesigned regarding process and impact data for GQT as there were limitations with the data collection as surveys were not matched pre and post GQT group programs. Participants were surveyed at each session ratherthan implementing surveys pre and post GQT group programs; hence it was difficult to assess the immediate impact of GQT following a group program.

Recommendations

Improving attendance and retention rates

Cooking programs promoted within health servicestend to attract clients who currently attend the service but such programs are unlikely to engage people who cannot cook or who don’t attend the service. In one study, women reported not being able to cook as well as their mothers and they commented that their grown children could hardly cook (8). Hence it is recommended that youth be targeted as well as embedding a mentoring system between Elders and the youth. GQT could also be implemented at community events that can potentially be an avenue of recruitment for GQT programs held at services.

Enhancement of existing programs

GQT could be facilitated within other existing groups like Mens’ groups and mums and bubs’ groups where participants may not necessarily attend a group that solely focuses on cooking. A ‘feed’ can also attract people to attend an organised group activity.

As has previously been discussed, focussing solely on cooking skills will not necessarily change behaviour or nutritional status. It is suggested that a Lifestyle Modification Program such as ‘Living Strong’, which was developed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, be combined with GQT as it encompasses most of the topics as suggested by facilitators and participants. Living Strong provides the knowledge base and GQT provides the practical cooking skills. Recently this concept has been implemented in some organisations and anecdotal evidence from facilitators has resulted in increased group retention rates and provides an informal supportive environment for participants to discuss the learnings over a meal.

Pass on concept

As there was limited evidence of the ‘pass on’ phase of GQT, the use of incentives such as: having competitions, the use of mobile phones as evidence of ‘pass on’ at home, and the creation of a Facebook GQT page have all been emphasised within the manual and at the information session. Facebook is considered to be an ideal social medium particularly if we want to target the youth for GQT. Facebook can also provide evidence of ‘pass ons’ within the community without formal evaluation data collected at programs. The ‘pass on’ to family and friends may make it more likely for success as it is a concept that is consistent with a cultural practice of learning new skills. Involving the family can also increase the effectiveness of nutrition interventions as the lack of family support can be a barrier to behaviour change (10).

Health promotion messages

Due to the high intake of sugary drinks consumed by participants, it is important to implement and initiate health promotion messages that focus on increasing water intake to deter people from drinking soft drink and/or sweetened beverages and to have water easily accessible during GQT sessions.

Conclusion

The results obtained from GQT are consistent with results obtained from other cooking programs (6, 7, 8) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and strengthens the evidence base that cooking programs to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are an effective strategy to increase cooking skills, confidence and knowledge for participants. These are skills and knowledge that can be maintained beyond the life of the program. However as is the case with many cooking programs it is difficult to evaluate the long term impacts on dietary intake which are also influenced by other factors apart from cooking skills and knowledge (8).

In conclusion, this article has described the pilot phase of GQT. The program has improved some participants’ confidence in cooking and changing their behaviour. It is a program that can be expanded with more effective evaluation processes to capture data. It may be useful to target the youth and people who do not know how to cook with a focus on a ‘hands on approach’ rather than cooking demonstrations.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the previous Nutrition Coordinator, Joanna Coutts, in the development and collection of this program and data. Furthermore, thanks to everyone who helped the development and implementation of Good Quick Tukka, your efforts do not go un-noticed and are very much appreciated.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 4727.0.55.003- Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Biomedical Results 2012-13 released 10/9/14, retrieved 23/9/14. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4727.0.55.003

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 4727.0.55.001- Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: First Results, Australia 2012-13 released 27/11/13 retrieved 14/8/14 http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/B1C2DDFB23B05FBBCA257C2F00145B2F?opendocument

- Browne J, Laurence S, Thorpe S (2009) Acting on food security in urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: Policy and Practice interventions to improve local access and supply of nutritious foods. Retrieved 9/8/2010 from http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/health-risks/nutrition/other-reviews

- Winkler E, Turrell G. Confidence to cook vegetables and the buying habits of Australian households J Am Diet Assos 2009; 109: 1759-68

- Vos T, Barker B, Stanley L, Lopez AD 2007. The Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2003, School of Population Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- Abbott P, Davidson J, Moore L, Rubenstein R Effective Nutrition Education for Aboriginal Australians: Lessons from Diabetes Cooking Course Journal of Nutrition Ed and Behaviour 2012; 44: 55-59

- Jamieson S, Herron B Evaluating the effectiveness of a healthy cooking class for Indigenous Youth. Aborig Isl Health Work J 2009; 33: (4): 6-7

- Foley W, Spurr S, Lenoy L, DeJong, et al. Cooking skills are important competencies for promoting healthy eating in an urban Indigenous health service Nutrition and Dietetics 2011; 68: 291-296

- Stead M, Caraher M, Wrieden W, Longbottom P et al. Confident, fearful and hopeless cooks Findings from the development of a food-skills initiative British Food Journal 2004; 106; 4: 274-287

- Abbott P, Davidson J, Moore L, Rubenstein R. Barriers and enhancers to dietary behaviour change for Aboriginal people attending a diabetes cooking course Health Promot J Austra 2010;21:33-8