Review of kidney health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

ReviewSchwartzkopff KM1, Kelly J1, Potter C2 (2020)

- The University of Adelaide

- Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet

Corresponding author: Christine Potter, email: healthinfonet@ecu.edu.au, ph: 6304 6336.

Suggested citation

Schwartzkopff, K.M., Kelly, J., Potter, C. (2020). Review of kidney health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 20(4). Retrieved from http://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/review-of-kidney-health-among-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people

The Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet has a strong commitment to quality and standards of scholarly excellence. All HealthInfoNet reviews are submitted for double blind review. This is considered the ‘gold standard’ for review. Nevertheless, as an additional step in our quality control processes we also electronically release the review for a period of post publication peer review by readers. Your comments, corrections and observations are most welcome and will significantly enhance the overall quality of the published review.

Please forward your comments to:

Christine Potter, Research Coordinator

Email: healthinfonet@ecu.edu.au

Ph: 6304 6336.

Download PDF 3.5MB

Table of Contents

- Key facts

- The context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and kidney health

- Kidney disease

- Estimates of the population who are living with kidney disease

- Hospitalisation and treatment

- Mortality

- Treatment and care of CKD and ESKD for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Strategies to improve kidney care in Australia for and with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Timeline of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kidney care

- Addressing systemic racism

- Concluding comments

- Glossary

- Acronyms

- References

Introduction

Kidney disease is a serious and growing health concern for people living in Australia [1]. It is reported that one in three adult Australians are at an increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) and around 10% of those who have CKD are unaware they have the condition [2]. Australians diagnosed with CKD regularly suffer poor health outcomes and their quality of life is often compromised [1]. CKD leads to a reduced functioning of the kidneys, or damage to the organs [3]. It has a number of stages and may also be associated with other chronic diseases including diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience an increased burden of kidney disease, especially those living in remote communities [4]. CKD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is dependent on multiple factors, is multilevel and accumulative [5]. Many of its risk factors are connected to social disadvantage and ongoing changes to lifestyle [6, 7]. Survey results from 2018-19 show that the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders reporting kidney disease has been consistent over the last decade, with levels higher in females than males [8]. The onset of kidney disease tends to be at an earlier age in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than for non-Indigenous people, increasing in age from early adulthood. In 2017-18, care involving dialysis was the leading cause of hospitalisation in Australia, responsible for 49% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander separations [9]. For the period 2011-2015, 2% (259) of deaths among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were a result of kidney disease and 2,268 deaths were listed where kidney disease was the associated cause of death [10]. If kidney disease is detected early enough, the progress of the disease can be slowed down and even stopped [8]. Addressing the factors that lead to kidney disease can reduce the impact of kidney disease, requiring tailored, culturally appropriate prevention and management programs and even broader actions beyond the Australian health care sector [1].

About this review

The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of key information on kidney health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia to:

- inform those involved or who have an interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and, in particular, kidney health

- provide evidence to assist in the development of policies, strategies and programs.

The review provides general information on the historical, social and cultural context of kidney health, and the behavioural factors that contribute to kidney disease. It provides information on the extent of kidney disease, including incidence and prevalence data; hospitalisations and health service utilisation and mortality. It discusses the prevention and management of kidney health problems, and provides information on relevant programs, services, policies and strategies that address kidney disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It concludes by discussing possible future directions for kidney health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia.

This review draws mostly on journal publications, government reports, national data collections and national surveys, the majority of which can be accessed through the HealthInfoNet’s publications database (http://aih-wp.local/key-resources/publications). This was not a systematic literature review in that not all articles were synthesised or assessed in the review. Rather, it was a scoping review, whereby the articles collected were used as the basis of the review, with further information sought during the drafting process.

Edith Cowan University prefers the term ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ rather than ‘Indigenous Australian’ for its publications. Also, some sources may only use the terms ‘Aboriginal only’ or ‘Torres Strait Islander only’. However, when referencing information from other sources, authors may use the terms from the original source. As a result, readers may see these terms used interchangeably in some instances. If they have any concerns, they are advised to contact the HealthInfoNet for further information.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are extended to:

- Kelli Owen, National Community Engagement Coordinator,National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce & AKction Reference Group member, for providing her expert perspective on this topic

- other staff at the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet for their assistance and support

- the Australian Government Department of Health for their ongoing support of the work of the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

Key facts

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience an increased burden of kidney disease, more so for those living in remote communities.

- The onset of kidney disease is often at an earlier age for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than for non-Indigenous people, increasing in age from early adulthood.

- In 2018-19, kidney disease was reported by 1.8% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- In 2018-19, the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people reporting kidney disease was around two times higher for females (2.3%) compared with males (1.2%).

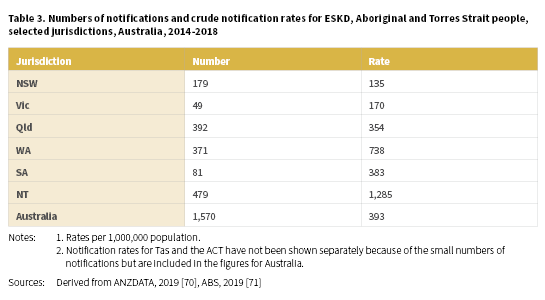

- A total of 1,570 (703 males and 867 females) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were newly identified with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) between 2014-2018 with a crude rate of 393 per 1,000,000 population.

- In 2017-18, there were 27,017 hospitalisations for chronic kidney disease (CKD)1 (excluding dialysis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a crude hospitalisation rate of 33 per 1,000.

- In 2015-17, after age-adjustment, the highest hospitalisation rates for CKD (excluding dialysis) by Indigenous region were in Tennant Creek (23 per 1,000); Apatula in the NT (18 per 1,000) and the West Kimberley and Kununurra regions in WA (15 per 1,000 for both).

- In 2014-18, the age-standardised death rate for kidney disease (as a major cause of death) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in NSW, Qld, WA and the NT was 19 per 100,000 population.

- In 2018, the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people commencing treatment for ESKD was 355.

- In 2018, there were 1,927 dialysis patients in Australia identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander with haemodialysis (HD) accounting for most of the treatment (92%).

- In 2017-18, there were 233,920 hospitalisations for regular dialysis (as a principal diagnosis) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a crude hospitalisation rate of 284 per 1,000 population (males: 248 per 1,000; females: 321 per 1,000).

- In 2015-17, 73% (27 out of 37) Indigenous regions had hospital separations for dialysis of 5,000 or more among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- In 2018, there were 48 new transplant operations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander recipients, representing 4.2% of all transplant operations in Australia.

- For 2009-2018, the survival rate among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who received an organ from a deceased donor was 85% at five years post-transplant.

- In November 2018, The Federal Government introduced a new MBS item to provide funding for the delivery of dialysis by nurses, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners and Aboriginal Health Workers in a primary care setting in remote

- There is increasing recognition of the unique peer support role that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with lived experience of kidney disease, dialysis care and transplantation can provide for other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people new to kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation and workup.

- Moving forward, there is increasing recognition of the need for primordial prevention, to prevent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people becoming ill with CKD.

The context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and kidney health

It is increasingly recognised that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people face additional challenges in health and wellbeing compared with other Australians, resulting in unacceptable gaps in health outcomes and mortality. The rapid and dramatic population loss caused by the introduction of new diseases, wars and genocide, and the forced removal of people from land and resources onto missions and fringe dwellings has had a lasting negative impact [11]. Throughout time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have passed on their knowledge and culture through oral traditions, but the widespread destruction of their population and societies has resulted in significant loss of languages, cultural practices and knowledge [12]. Ongoing marginalisation, separation from culture and land, food and resource insecurity, intergenerational trauma, disconnection from culture and family, racism, systemic discrimination and poverty, have resulted in poorer physical and mental health for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and an increase in chronic conditions including CKD [13, 14].

The social determinants of health are widely accepted as a model to explain how social factors influence an individual’s health, however Australia’s health system continues to focus predominantly on the western, biomedical definition of illness and disease, the identification of disease and treating of body parts [15]. Hospitals are divided into specialities, and there is an underlying expectation that individuals will have the required resources to maintain their own health and wellbeing and effectively navigate health care services [16]. Indigenous concepts of health and wellbeing are more holistic and collective, and include cultural determinants, they are centred around the importance of culture, family, Country, connectedness and relationships [17]. The strengths and priorities of Indigenous people have often been overlooked within western health care delivery and policy. These two different world views and priorities lead to cultural clash and miscommunication, which in turn has impacted on access to, and quality of care [16].

In 2007, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) (now replaced with the National Cabinet) set measurable targets to track and assess developments in the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [18]. This National Indigenous Reform Agreement, known as Closing the Gap aimed to achieve equality of health status and life expectancy between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non-Indigenous Australians by 2030 [18]. This included a commitment to:

- Developing a comprehensive, long-term plan of action, that was targeted to need, evidence-based and capable of addressing the existing inequalities in health services.

- Ensuring the full participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their representative bodies in all aspects of addressing their health needs.

In 2018, COAG approved the Closing the Gap Refresh which was guided by the principles of empowerment, self-determination, and community-led, strengths-based strategies. In July 2020, a new agreement, which built on and replaced the 2008 agreement, was signed by the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations (Coalition of Peaks) and the Australian Governments [19]. The objective of this agreement is to overcome the entrenched inequalities faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, so their life outcomes are equal to all Australians. The outcomes of this agreement include:

- shared decision-making

- building the community-controlled sector

- improving mainstream institutions

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led data

- sixteen socioeconomic outcomes to be met at a national level.

Kidney disease

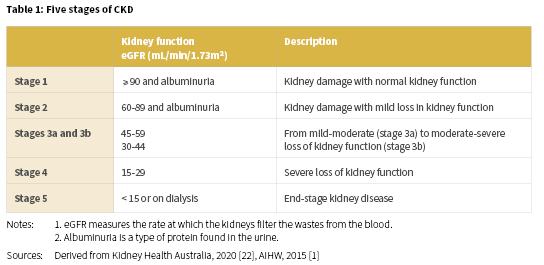

Kidney disease, renal and urologic disease, and renal disorder are terms that refer to a variety of different disease processes involving damage to the filtering units (nephrons) of the kidneys which affect the kidneys’ ability to eliminate wastes and excess fluids [20]. Of particular importance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, is CKD, which is defined as kidney damage or reduced kidney function that lasts for three months or more. CKD is inclusive of a range of conditions, including diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive renal disease, glomerular disease, chronic renal failure, and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) [21]. CKD is usually categorised into five stages which depend on kidney function or the evidence of kidney damage (Table 1) [1].

Established risk factors for kidney disease

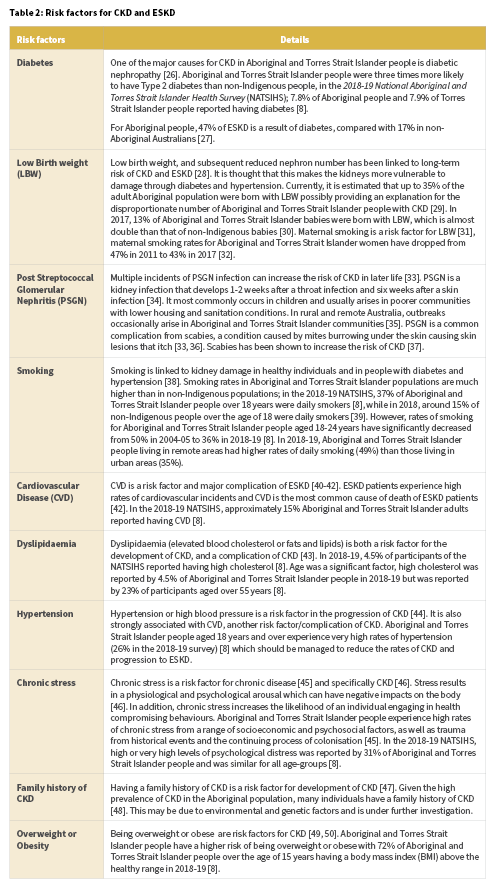

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are at disproportionate risk of developing CKD and ESKD and also developing CKD and ESKD at younger ages compared with the general population [23]. Disease pathways for CKD and ESKD are complex and not fully understood, however there are a number of known risk factors (Table 2). The risks listed have been established as correlated but not necessarily causative. There are both biological and social pathways that contribute to risk [24, 25]. In order to reduce Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s risk of CKD and ESKD, a comprehensive and holistic approach is required.

The role of primary health care in helping to address established risk factors for CKD

Attending to holistic health, including social and cultural wellbeing needs, has been shown to be effective in reducing or preventing chronic disease [51]. Successfully addressing risk factors requires a comprehensive primary health care and holistic approach which takes into account the historical and social context for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Often successful programs are led by, or work in collaboration with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, communities, health professionals and services [52]. This is exemplified by a 2012 program developed in New South Wales (NSW) where an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) employed a nurse practitioner to systematically screen and treat CKD [53]. The project identified a high number of patients with CKD who were previously undiagnosed and improved collaboration with nephrologists through telehealth. Additionally, the Antecedents of Renal Disease in Aboriginal Children and Young People (ARDAC) study is a longitudinal study that monitors the heart and kidney health of Aboriginal and non-Indigenous children and young people in NSW. If participants return abnormal test results, they are referred to a local health centre [54].

Health programs and services such as those provided by and with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) actively provide culturally safe healthcare to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities [55]. There is recognition that additional support and resources are often required in order to achieve equality in health and wellbeing outcomes.

Patient informed clinical guideline development

Currently in Australia, there are no national clinical guidelines regarding renal care specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. In 2018, Kidney Health Australia – Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment (KHA-CARI) Guidelines aimed to develop an inaugural clinical guideline for the ‘Management of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Maori’ [56]. Three specific strategies were devised in Australia to ensure the guideline will be underpinned by recommendations identified from within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and that reflect and support the needs of clinicians. These three strategies included: 1) the engagement of a panel of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health clinicians; 2) targeted consultations with locally based Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers and services and 3) consultation and feedback from the Australian national peak organisations. In recognition that it would not be appropriate to follow the usual approach to writing guidelines via a literature review followed by a short community consultation, a plan was developed to conduct national community consultations and a literature review simultaneously.

Consultations in metropolitan, regional and remote areas have been conducted. Three were undertaken in Darwin, Alice Springs and Thursday Island in the Catching Some Air Project [57], and three in South Australia (SA) in the AKction project [58]. Kidney Health Australia (KHA) has been conducting further consultations in Western Australia (WA), Queensland (Qld) and NSW. At the time of this review, further planned consultations have been impacted by COVID-19. Priorities identified by community members to date include kidney disease prevention and early detection, rural and remote education involving family, storytelling and face-to-face workshops to improve access to care, stabilising local workforce, encouraging availability of expert Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients to provide peer education and support, improved access to interpreters and language resources and reliable transportation to care [59].

Estimates of the population who are living with kidney disease

There are various ways that kidney disease is measured in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, including prevalence, incidence, health service utilisation, mortality and burden of disease. It should be noted however, that:

- the availability and quality of data vary

- there are data limitations associated with each of the measures of kidney disease

- statistics about kidney disease for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are often underestimated

- readers should refer to source documentation for specific methodological information.

Measuring kidney disease

The various measurements used in this review are defined below.

Incidence is the number or proportion of new cases of kidney disease that occur during a given period.

Prevalence is the number or proportion of cases of kidney disease in a population at a given time.

Age-specific is the estimate of people experiencing a particular event in a specified age-group relative to the total number of people ‘at risk’ of that event in that age-group.

Age-standardised is a method of removing the influence of age when comparing populations with different age structures. This is necessary because the rates of many diseases increase with age. The age structures of the different populations are converted to the same ‘standard’ structure; then the disease rates that would have occurred with that structure are calculated and compared. This method is used when making comparisons for different periods of time, different geographic areas and/or different population sub-groups (for example, between one year and the next and/or states and territories, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous populations). They have been included in this review for users to make comparisons that may not be available in this report.

Hospitalisation is an episode of admitted patient care, which can be either a patient’s total stay in hospital (from admission to discharge, transfer or death), or part of a patient’s stay in hospital that results in a change to the type of care (for example, from acute care to rehabilitation).

Hospital separation rate is the total number of episodes of care for admitted patients divided by the total number of persons in the population under study. Often presented as a rate per 1,000 or 100,000 members of a population. Rates may be crude or standardised.

The underlying cause of death is the disease that started the sequence of events leading directly to death. Deaths are referred to here as ‘due to’ the underlying cause of death.

Associated causes of death are all causes listed on the death certificate, other than the underlying cause of death. They include the immediate cause, any intervening causes, and conditions which contributed to the death but were not related to the disease or condition causing the death.

The most recent data on the prevalence of kidney disease/CKD are from self-reported survey data from 2018-19 [8], biomedical survey data from 2012-13 [3] and various community based research reports and screening programs [4, 6, 60-67].

(Further information on community based reports and screening programs is available on the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet website.)

Prevalence and incidence of kidney disease

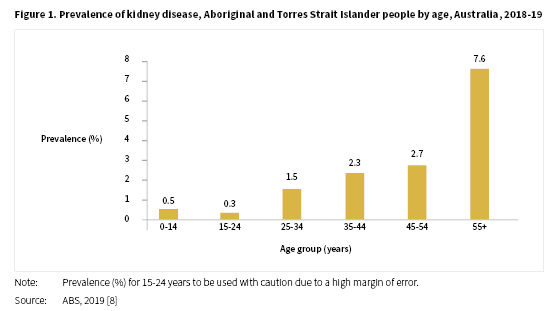

In the 2018-19 NATSIHS, kidney disease was reported by 1.8% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a result similar to that reported in the 2012-13 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (AATSIHS) of 1.7% [8]. The proportion of people reporting kidney disease in 2018-19 was around two times higher for females (2.3%) compared with males (1.2%). The levels of kidney disease reported increased with age from 0.5% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 0-14 years to 7.6% for those aged 55 years and over (see Figure 1).

In 2018-19, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in the Northern Territory (NT) reported the highest proportion of kidney disease (3.7%), followed by WA (2.9%) and Qld (1.6%). The remaining jurisdictions reported levels between 1.5% for Victoria and 0.3% for Tasmania2 [8]. The proportion of people with kidney disease increased with remoteness from 1.2% for people living in major cities, 1.6% in regional areas, 3.2% in remote areas and 3.8% in very remote areas.

The 2012-13 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Measure Survey3, 4 (NATSIHMS) collected blood and urine samples to test for chronic disease markers including CKD [3]. Kidney function was measured by two tests: estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urinary albumin creatinine ratio (ACR). The tests only indicated a stage of CKD and not a diagnosis of CKD. In 2012-13, 18% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, aged 18 years and over, had indicators of CKD with similar proportions for males (19%) and females (17%). The prevalence of CKD increased with age, with the highest proportion being 40%, in the 55 years and over age-group. The proportion of people with indicators of CKD was higher in remote areas (34%) compared with non-remote areas (13%), with the proportion in very remote areas (37%), over three times the proportion in major cities (12%). Of the 18% of people who had indicators of CKD, only 11% self-reported having the condition which suggests that around nine in ten people with signs of CKD were not aware they had it. This reflects that CKD remains a highly undiagnosed condition.

In 2012-13, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT, the NT had the highest proportion of people with indicators of CKD (32%), followed by WA (23%), Qld and SA (18%) and NSW (15%) [3]. For further information on the analysis of biomedical results from the survey refer to: Profiles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney disease.

With most information on CKD limited to self-reported data, the primary focus in the literature has been on ESKD which is reported routinely to the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA); the data are collated and detailed in annual surveillance reports [21, 68, 69]. Rates for ESKD fluctuate from year to year but in recent years Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rates have been increasing [21].

A total of 1,570 (703 males and 867 females) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were newly identified with ESKD between 2014-2018 with a crude rate of 393 per 1,000,000 population (Table 3) (Derived from [70, 71]). The highest notification rates of ESKD for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were recorded in the NT (1,285 per 1,000,000), WA (738 per 1,000,000) and SA (383 per 1,000,000).

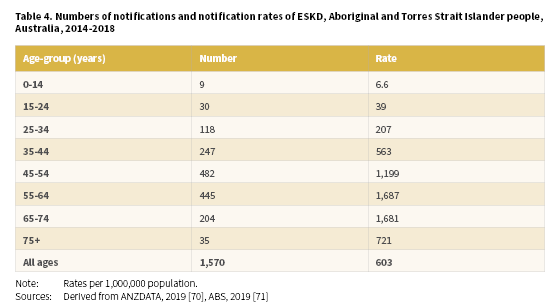

Of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people newly registered with the ANZDATA in 2014-2018, 56% were aged less than 55 years of age (Derived from [70, 71]). Age-specific notification rates increased with age from the 0-14 years age-group through to the 65-74 years age-group before declining for the 75 and over age-group (Table 4). The highest rates were recorded in the 55-64 years age-group (1,687 per 1,000,000) and 65-74 years age-group (1,681 per 100,000).

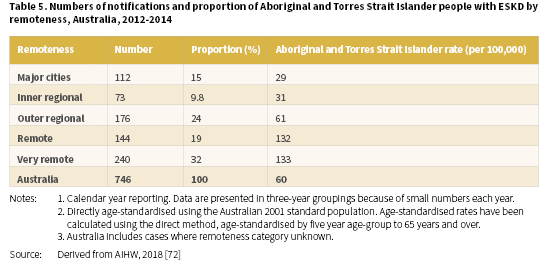

The high rates of ESKD are a major public health issue for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and especially for those living in remote and very remote areas of Australia. In 2012-2014, the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with ESKD varied across remoteness categories [72]. The lowest proportion with ESKD were living in the inner regional areas (9.8%) and the highest in very remote areas (32%) (Table 5). Age-standardised rates increased with remoteness, from 29 per 100,000 in major cities through to 133 per 100,000 in very remote areas.

Hospitalisation and treatment

Hospitalisation data are not a reliable indicator of the level of kidney disease in the community but do provide some information of the impact of the disease and about who is accessing services. Dialysis treatment is the most common reason for hospitalisation in Australia, with patients needing to attend hospital or a satellite centre three times a week for treatment [10]. A person who has recurrent hospitalisations for the same reason (for example, dialysis) will be counted multiple times. It is therefore important to separate hospitalisation rates for dialysis from hospitalisation rates for other conditions.

There is some under-identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the National Hospital Morbidity Database but data for all states and territories are considered to have adequate identification from 2010-11 onwards [73]. An AIHW study found that the ‘true’ number of hospitalisations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients nationally, was about 9% higher than reported.

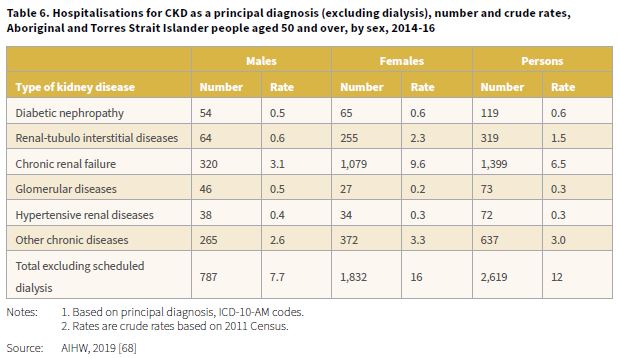

The 2019 report, Insights into vulnerabilities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 50 and over provided hospitalisation data for the period 2014-16 by type of kidney disease [68]. When dialysis was excluded, there were 2,619 hospitalisations for CKD, corresponding to a crude rate of 12 per 1,000 (Table 6). The highest hospitalisation rate when dialysis was excluded was for chronic renal failure, 1,399 separations with a rate of 6.5 per 1,000. The rate for CKD (excluding dialysis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females compared with males was 2.1 times higher (16 and 7.7 per 1,000 respectively).

In 2017-18, there were 27,017 hospitalisations for CKD as a principal and/or additional diagnosis (excluding dialysis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a crude hospitalisation rate of 33 per 1,000 [20]. Rates were highest among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females (39 per 1,000) compared with males (27 per 1,000).

In 2015-17, there were 5,998 hospitalisations for CKD as a principal diagnosis (excluding dialysis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a crude hospitalisation rate of 4.0 per 1,000 [74]. Rates were 1.9 times higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females (5.2 per 1,000) compared with males (2.8 per 1,000). Hospitalisation rates increased with age from 0-4 years through to 55-64 years (except for the 10-14 years age-group) with the highest age-specific crude rates recorded for the 55-59 years age-group (16 per 1,000) and the 60-64 years age-group (11 per 1,000). Rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 65 years and over were also high at 10 per 1,000.

Information is available for CKD hospitalisations (excluding dialysis) by Indigenous regions5 [74]. The Indigenous regions geographical classification (IREG) enables comparisons that reflect the distribution of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (compared to the total Australian population). In 2015-17, the highest reported numbers of hospitalisations were in the NSW Central and North Coast (763), followed by Brisbane (476), Perth (310), Cairns-Atherton (303) and Apatula in the NT (299). After age-adjustment, the highest rates were recorded in Tennant Creek (23 per 1,000 population in the IREG) and Apatula in the NT (18 per 1,000). These were followed by the West Kimberley and Kununurra regions in WA (15 per 1,000 for both). The lowest rates were reported for most of NSW, Victoria (Vic), Tasmania (Tas), ACT, Brisbane and Adelaide with less than five hospitalisations per 1,000.

Hospitalisation rates, adjusted for age, for CKD (excluding dialysis) were higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females than males in 32 of the 34 IREGs where calculations were possible6 [74]. The five highest hospitalisation rates were all among females: Tennant Creek (33 per 1,000); West Kimberley and Apatula (both 21 per 1,000); Kununurra (17 per 1,000) and Nhulunbuy in the NT (15 per 1,000). For males, the highest rates were recorded for Tennant Creek (14 per 1,000); Apatula (13 per 1,000); Kununurra (12 per 1,000) and Kalgoorlie and Mount Isa (both 9 per 1,000). For further information on the CKD hospitalisation rates (excluding dialysis) by IREG, refer to: Profiles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney disease.

Mortality

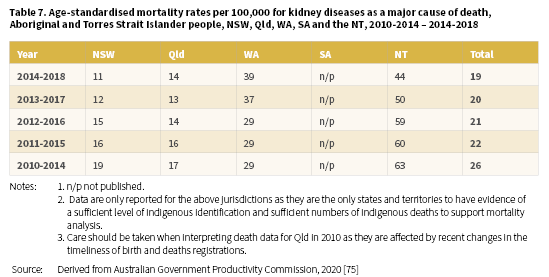

In 2014-2018, the age-standardised death rate for kidney disease (as a major cause of death) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in NSW, Qld, WA, SA7, and the NT was 19 per 100,000 population (Table 7) [75]. The highest rate for this period was reported for the NT; 44 per 100,000 with WA the next highest, with a rate of 39 per 100,000. Information on five-year aggregated data for the years 2010-2014 to 2014-2018 reveals a similar pattern for the NT and WA.

For the period 2011-2015, 2% (259) deaths among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were a result of kidney disease [10, 72]. In the same period, 2,268 deaths were listed with kidney disease being the associated cause of death [10].

Information about CKD as an underlying or associated cause of death is available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT for 2016-2018. The crude death rate was 72 deaths per 100,000 (males: 64 per 100,000; females 80 per 100,000) [20].

Treatment and care of CKD and ESKD for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

If CKD is left untreated, kidney function can decrease to the point where kidney replacement therapy (KRT), in the form of dialysis (mechanical filtering of the blood to help maintain functions normally performed by the kidneys) or transplantation (implantation of a kidney from either a living or recently deceased donor) may be necessary to survive [76]. The aim of treatment of CKD is to slow the progress of the disease, reduce the risk of developing CVD and prevent and manage complications of the disease [77]. KRT cannot cure kidney disease but can enable survival [78]. ESKD, where the kidneys are operating at less than 15% of capacity and dialysis or transplant are required [79], is expensive to treat [80] and has a marked impact on the quality of life of those who suffer from the disease as well as those who care for them [81, 82]. Patients and their families or carers should be provided with appropriate information about ESKD, together with options for treatment, so they can make an informed decision about the management of their illness [83]. The treatment options for ESKD involving KRT are dialysis (peritoneal dialysis (PD) or haemodialysis (HD)) and transplantation [78, 83, 84].

In 2018, the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people commencing KRT for ESKD was 355 [85]. For the period 2014-2018, numbers fluctuated yearly, however HD remained the most common form of KRT for people commencing treatment for ESKD (Table 8).

The number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with treated ESKD at the end of 2018 was 2,224 [85]. The number on KRT continued to increase over the period 2014-2018 from 1,819 in 2014 to 2,224 in 2018 (Table 9). There were clear differences in treatment modalities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with most treated with HD (between 80-81%). The proportion with a transplant as a long-term treatment for ESKD was consistent over the period at 12-13%.

For more detailed information on incidence and prevalence refer to the dialysis and transplant sections of this report.

Dialysis

Personal impact of diagnosis and transition to dialysis

Receiving a diagnosis of CKD and ESKD often has a significant impact on a person and their way of life. Shock at their initial diagnosis and feeling overwhelmed with the enormity of their situation is common [86, 87]. Patients grapple with changes to their way of life; spending hours each week undergoing dialysis, experiencing fatigue and limited physical capabilities, and an interruption of their work and personal life. The impacts of CKD and ESKD extend beyond the person with the disease, they also impact on carers and loved ones. Patients have expressed worry about the burden placed on their children and family members as a result of their condition [86, 87].

‘Your life is committed to that machine.’ Participants became aware of the drastic changes in their lifestyle and restrictions imposed by dialysis. Being unable to work at home or travel to paid employment, visit family or take a holiday were common.

Dialysis changes our life, just like that you know. Yeah, we can’t even do things and can’t go anywhere … used to go out every day, go away to get work. Now can’t even push the mower. It messes the fistula’. [86, p.89]

The fact that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience CKD and ESKD at younger ages adds an additional burden [88]. This means that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are still trying to complete their education, work, pay their homes and mortgages while commencing dialysis and renal treatments. In order to help provide support to patients during an overwhelming and confusing period, a range of peer support programs are emerging which are discussed later in this review.

Incidence and prevalence of dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis (PD)

PD works inside the body using a patient’s natural peritoneal membrane as a filter which allows impurities to be drawn out of the blood [83, 84, 89]. PD uses a soft tube called a catheter which remains in the body until dialysis is no longer needed. Special PD fluid called dialysate (containing glucose and other substances similar to those in a patient’s blood) is pumped into the abdomen via the catheter. The body’s waste products pass from the bloodstream across the peritoneal membrane and into the dialysate. After a few hours, the used dialysate is drained out of the body and replaced with fresh solution. The process where dialysate is replaced by a fresh solution is called an ‘exchange’, taking about 30-45 minutes, usually four times per day. This form of PD is known as continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). PD can also be performed using a machine to facilitate the ‘exchange’ known as automated peritoneal dialysis (APD). APD takes place during the night for 8-10 hours with the patient connected to the machine for the whole duration of the exchanges.

Haemodialysis (HD)

HD involves making a circuit where blood is pumped from the patient’s bloodstream to a dialysis machine that filters waste and excess water [83, 84, 89]. The filtered blood is then pumped back into the bloodstream. HD can be performed at home, a satellite dialysis unit located in the community or a hospital dialysis unit. The number of treatments varies depending on the location of treatment; usually 3-5 per week for home-based HD and three per week for centre-based HD. The duration of the treatment is between 4-6 hours per treatment session.

Information from ANZDATA is available for 2018 when a total of 305 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with ESKD commenced dialysis, a decrease from 2017 (355 people) [85]. The majority (88%) were treated with HD as their initial KRT with only 12% accessing PD as a first treatment. The NT accounted for the highest rate of patients commencing dialysis.

HD, conducted in clinics and hospitals (including satellite centres) in large urban settings, is the most common form of dialysis treatment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with ESKD [85, 90, 91]. The delivery of dialysis8 in most remote communities is not currently provided, reflecting distance, a small population and the related costs to provide infrastructure and specialised staff [93]. In 2018, there were 1,927 prevalent dialysis patients in Australia (PD and HD treatments) identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander [85]. HD accounted for the majority of treatment (92%), with only 7.6% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander dialysis patients receiving peritoneal dialysis (PD) (Derived from [85]). The highest proportion of patients on dialysis were from the NT (34%), followed by Qld (24%) and WA (23%).

Hospitalisation and dialysis

In the 2019 report, Insights into vulnerabilities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 50 and over, data for the period 2014-16 indicated that for all hospitalisations for CKD, regular dialysis was the most common type of hospitalisation with 290,151 separations [68]. The crude hospitalisation rate was 1,351 per 1,000. The rate among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females for regular dialysis was 1.4 times higher compared with males (1,579 and 1,100 per 1,000 respectively).

In 2017-18, there were 233,920 hospitalisations for regular dialysis (as a principal diagnosis) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a crude hospitalisation rate of 284 per 1,000 population (males: 248 per 1,000; females: 321 per 1,000) [20].

Detailed information is also available on hospitalisation for dialysis for CKD in the period 2015-17 [74]. In this period, there were 460,944 hospital separations9 of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This represented a crude hospitalisation rate of 309 per 1,000 population with females 1.4 times more likely to be hospitalised with CKD compared with males (359 and 260 per 1,000 respectively). Hospitalisation rates increased with age from 0-4 years through to 60-64 years with the highest age-specific crude rate recorded for the 60-64 years age-group (1,748 per 1,000) before decreasing to 1,501 per 1,000 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 65 years and over.

Information is also available for dialysis hospitalisations by Indigenous regions [74] 10,11. In 2015-17, 73% (27 out of 37) IREGs had CKD hospital separations of 5,000 or more among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This indicates the high levels and wide coverage of dialysis for this population. The five highest reported numbers of hospitalisations were in Apatula in the NT (41,752); Perth (30,558); Townsville-Mackay (23,610); Cairns-Atherton (22,864) and Tennant Creek (21,113). After age-adjustment, the highest rates were recorded in Tennant Creek (3,397 per 1,000 population in the IREG) and Apatula in the NT (3,235 per 1,000). These were followed by the West Kimberley, Broome and Kalgoorlie regions in WA (1,919, 1,622 and 1,508 per 1,000 respectively).

Age-adjusted hospitalisation rates for dialysis were higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females than males in 22 of the 37 IREGs [74]. The five highest hospitalisation rates among females were in Tennant Creek (4,182 per 1,000); Apatula (3,450 per 1,000); West Kimberley (2,264 per 1,000); Broome (2,207 per 1,000) and Kalgoorlie (1,697 per 1,000). For males, the highest rates were recorded for Apatula (2,840 per 1,000); Tennant Creek (2,598 per 1,000) and West Kimberley (1,506 per 1,000). For further information on the hospitalisation rates for dialysis by IREG refer to: Profiles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney disease.

In 2014-15, there were 207,605 hospital separations12 for ESKD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a crude hospitalisation rate of 288 per 1,000 [94]. After age-adjustment, the hospitalisation rate for ESKD for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was 491 per 1,000. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females had the highest rate of hospitalisation for ESKD at 551 per 1,000 and males were hospitalised for ESKD at a rate of 425 per 1,000.13 Hospitalisation rates for ESKD for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people increased with remoteness from 169 per 1,000 in major cities, 240 per 1,000 in regional areas and 596 per 1,000 in remote and very remote areas. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in remote and very remote areas, the crude hospitalisation rate was 3.5 times the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in major cities.

Mortality of dialysis patients

In 2018, 215 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people receiving dialysis died (Derived from [85]). The most common causes of death for dialysis patients were CVD (62 deaths) and withdrawal from treatment (51 deaths) (Table 10). For the period 2014-2018, CVD and withdrawal from treatment were the main contributors to the deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on dialysis.

Psychosocial reasons were cited as the most common reason for dialysis patients to withdraw from treatment [85].

Survival on dialysis

ANZDATA data shows that for the period 2009-2018, 60% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who started dialysis were alive five years later [85].

Transplantation

For most people kidney transplantation is the optimal treatment for ESKD [82]. Transplantation involves surgically implanting a kidney into a patient with ESKD from either a living or deceased donor [83]. It is a treatment for kidney failure but not a cure.

The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who receive a kidney transplant is very low [85]. In 2018, there were 48 new transplant operations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander recipients, representing 4.2% of all transplant operations in Australia [85]. This proportion varied little over the period 2014-2017, from 4.5% in 2014, 3.7% in 2015 and 3.1% for both 2016 and 2017. Two pre-emptive kidney transplants (transplant performed before the initiation of dialysis treatment) were accessed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in 2018, with a total of eight being accessed over the period 2014-2018.

It is more common for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to receive a kidney from a deceased donor than a living donor [85]. Information for the period 2009-2018 reported the number of transplant recipients from a living donor at 21, and from a deceased donor, 302. There are many possible explanations for the low numbers receiving a transplant (especially from a live donor) [78, 82]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experiencing high levels of comorbidities at the commencement of KRT may exclude them from being suitable candidates for transplantation. These comorbidities may also explain why fewer people are able to donate their kidneys to relatives. Poorer post-transplant outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may also pose a barrier to transplantation [82, 95, 96], and therefore make them less likely to be listed for a kidney transplant than other Australians [97].

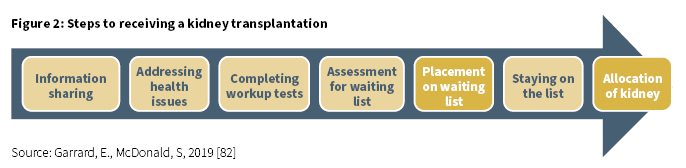

At the end of 2018, 43 (4.5%) of the 96614 patients on the waiting list for a transplantation were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander [85]. This was a 39% increase from 2017 when 31 (3.2%) patients were on the waiting list (Derived from [85]). Being assigned to the kidney transplant waiting list is the result of a series of steps and assessments which must be adhered to (Figure 2) [82]. If this process is not well managed, these steps may become barriers to being allocated a place on the waiting list.

A study, based on ANZDATA from June 2006 to December 2016, on the disparity of access to kidney transplantation by Indigenous status found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians on dialysis were less likely than non-Indigenous people to be placed on the kidney waiting list, and this was even greater for older patients, and those residing in remote areas [97]. Of the 217 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the waiting list in the study:

- 96 (44%) were females

- the median age for commencement of KRT was 43 years of age

- comorbidities were higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (except for cerebrovascular disease)

- 39% did not present with any comorbidities

- the median time to kidney transplantation after being on the waiting list was 266 days

- 135 (62%) received a deceased donor kidney

- 17 (7.8%) of transplant waiting list patients died.

Survival following transplantation

According to ANZDATA data for the period 2009-2018, the survival rate among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who received an organ from a deceased donor was 85% at five years post-transplant [85]. Every year over the first five post-transplant years, some kidney transplants (from a deceased donor), can be lost through transplant failure or a patient dying with a functioning kidney. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 72% had transplant kidney function five years post-transplant. Compared with non-Indigenous people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have higher mortality rates in the first five years post-transplant, with the difference apparent at three years post-transplant.

A systematic review of studies published between 2004 and 2018 examined patient survival and other post-transplant outcomes among Indigenous people from Australia, Canada, the United States and New Zealand, compared with non-Indigenous people [98]. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, compared with non-Indigenous Australians the review found that there was:

- A lower five-year survival rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in WA (a survival proportion of 0.64 versus 0.86).

- A higher risk of death (after adjusting for age and sex) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in northern Australia; however, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous people residing outside of this region there was no difference in the survival of patients.

- Overall, patient survival, graft survival and delayed graft function were significantly reduced among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, irrespective of geographical location, age or evidence of pre-existing conditions (comorbidities).

Palliative care

Currently there is mixed use and meaning of the terms: palliative care, supportive care, conservative care and end-of-life care in Australian kidney care. For the purposes of this review, and on advice of a palliative nephrologist [99]; supportive care, conservative care and end-of-life care are positioned as different aspects of palliative care.

Palliative care is the provision of physical, psychosocial and spiritual support for people and their loved ones facing problems related to a terminal or life-threatening illness, such as ESKD [100]. Palliative care is a human right that needs to be available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, of good quality, culturally appropriate and accessible. Evidence shows that the involvement of palliative care services can improve the quality of life for patients by managing the symptoms that cause suffering. Palliative care provision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may be particularly complex due to a multitude of factors including language and communication barriers, cultural and belief differences and lack of access to services (particularly for rural and remote people). Culturally safe and responsive palliative care adapts to these challenges.

Conservative, supportive and end-of-life care are different but related forms of palliative care for CKD and ESKD patients [101], and patients should have the right to choose their preferred mode of treatment from those that are clinically available to them, in consultation with their health care team.

Conservative care or comprehensive supportive kidney care refers to care of patients who are not able, or prefer not to, undergo dialysis [102]. Conservative care is still considered to be an active form of care that includes all other facets of care other than dialysis. Conservative care aims to slow the progression of kidney disease through control of other factors such as blood glucose and blood pressure [101]. As renal function declines, fewer interventions are made and the focus moves to the control of symptoms [103]. This option is usually made with patients, taking into consideration their lifestyle, overall health and wellbeing, the complexity of treatments and their outcomes. Conservative care is usually managed in the community with the supervision and support of health professionals including a GP, a nephrologist (kidney health specialist), specialist nurses, a social worker, a dietitian and a palliative care team [84].

Supportive care refers to symptom management of ESKD [22]. Supportive care can be introduced in the early stages of disease when symptoms are distressing (for example, itching and restless legs). Supportive care can be provided for both patients who are undergoing KRT as well as for those who are not undergoing KRT [104]. The level of supportive care is often increased towards end-of-life, as symptoms are likely to worsen at this stage.

Some patients seek to withdraw from dialysis due to the challenges that they face in their treatment [105]. Most ESKD patients will not live long after the discontinuation of dialysis. Therefore, dialysis withdrawal triggers the commencement of end-of-life care and coordination between renal and palliative care teams.

Patient perspective

Despite the prognosis of ESKD for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, some research indicates that palliative care is not a well-known service. There is limited literature discussing palliative care experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kidney patients. One study from WA specifically explored the experience of palliative care with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander renal patients. The study found that the term palliative care is not well known and for those who knew the term, it was not well understood despite the fact that palliative care had been embedded in the kidney disease care pathway for almost a decade [106]. This is an indication that the health service failed to communicate palliative care options in an effective way. In the study almost all participants contemplated death and dying and expressed a desire to better understand their options for palliative care. All participants knew how they wanted to spend the end of their life and had clear end-of-life wishes. This experience was mirrored in older articles describing other Aboriginal patient experiences of palliative care [107, 108]. This suggests that if a conversation was initiated, patients would have clear ideas of what they want; however, initiating discussions prematurely may mean that patients are too overwhelmed or end up being forgotten [106]. Therefore, it is preferable that end-of-life discussions be conducted respectfully and carefully at regular intervals as circumstances many change.

Improving palliative care

Providing palliative and end-of-life care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people requires skills in communication and cultural understanding. The Program of Experience in the Palliative Approach (PEPA), a project funded by the Federal Government, has developed a set of guidelines which outline the cultural considerations when providing end-of-life care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [109]. PEPA also provide a learning guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and can provide training to health professionals. The guidelines outline a number of factors to be aware of when caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the end-stage of their life. For example, one key factor to be aware of is that most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people live in collective societies and patients and/or their families may nominate a spokesperson or decision maker who is not the patients next of kin.

Another important consideration is the importance of returning to Country before the end-of-life. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people believe that a person’s spirit stays in the location where they have passed on [109]. This makes it very important that people can return to Country prior to their passing. If this is not possible and they die away from Country, smoking ceremonies or other cultural ceremonies can be conducted to allow the release of the spirit to go back home. Best practice is that all efforts be made to enable someone to get back to Country before they pass on.

One example of work that has been done in this area is the use of patient journey mapping to plan an end-of-life journey for a patient in the Managing Two Worlds Together Study [110]. In the study, a patient journey mapping tool was co-developed to examine the patients’ journey through the health care system as well as the priorities, concerns and commitments of the patient, the priorities of the family or carer, and the priorities of the health service. The tool identified where the priorities and concerns of the patient and their family were mismatched with those of different health service providers. This allowed a conversation between the health care providers and the patient and families and strategies to mitigate the mismatch were developed. In one particular case study, a renal patient was entering the end of her life and her main priority was to get back home to be with her family and community and be on Country. This was difficult for the health service to accommodate due to her rapidly failing health. However, once the renal manager identified the importance of her returning home as part of her end-of-life plan, the health service was able to prioritise and organise her return home, just in time.

(For more information about palliative and end-of-life care see http://aih-wp.local/learn/health-system/palliative-care.)

Care considerations

Mental health

Qualitative evidence suggests that CKD and ESKD has a detrimental impact on people’s emotional wellbeing [86]. There is currently a gap in the literature on the statistical prevalence of depression for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander CKD patients, however an international systematic review and meta-analysis of mainstream populations identified that 23% of assessed CKD patients exhibited depressive symptoms, with the number increasing to 39% for stage 5 CKD patients [111]. This compares to 13% for the whole population [112]. Depression has been linked to poorer quality of life and health outcomes in CKD and ESKD patients [113] and it is therefore essential to incorporate treatment of mental health into CKD and ESKD treatment plans. Practical guidelines for prescription of antidepressants for CKD patients are available [114]. There are very few published studies or programs targeting mental health specifically for Indigenous CKD patients. The Wellbeing Intervention for Chronic Kidney Disease (WICKD) study aims to use a wellbeing app for keeping Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kidney patients mentally strong throughout their illness; the results of this study are yet to be published [115].

Rural and remote access and relocation

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are underrepresented in transplantation, peritoneal dialysis, and home-dialysis services, and are overrepresented for haemodialysis [90, 116]. The frequency of dialysis unit haemodialysis treatments (three times a week) means that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have to leave their homes in rural and remote areas and relocate to regional and city locations in order to receive care. This often results in kidney patients’ experiencing isolation and grief from being away from their family and communities, being unable to participate in significant cultural events, and feeling disconnected from Country. As described in one report:

‘It may not be an exaggeration to say that moving to the city to undertake dialysis allows life-continuing treatment, but removes people from all that is important in life’. [90, p.11]

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in remote communities have a strong desire to be able to receive care on Country and be cared for by their own family and community or mob [117]:

‘We need more consultation with the government, about getting more renal dialysis machines over there [in communities], keeping family on country, and maybe train them up on how to be on the dialysis machine, with local renal nurses to train and teach our mob to do things for ourselves’. [117, p.22]

In order to mitigate these issues, a number of programs have been developed, including the SA Health Mobile Dialysis Bus [93], the Kimberley Renal Services Mobile Dialysis Unit (MDU) [118] and the Purple House Dialysis Truck [119], all of which support remote kidney patients to return to their homelands for significant events, funerals and to reconnect with family and Country. ‘The Purple Truck’ has two dialysis chairs and is used to support longer home visits, provide education and information to remote communities and to manage demand where needed [119]. An additional role is educating young people about how to avoid ESKD and explaining the dialysis process.

An evaluation of the SA Health service identified that it provided much needed respite for patients who needed to attend events and/or had been disconnected from Country [93]:

‘The bus is really good for us, it gives us a chance to get home so we can have a voice.’

‘It is really good to see the whole family and that place. That feeling make me happy’. [93, p.7]

Staff of the bus also observed this positive impact with one staff member stating:

‘They were transformed. They were completely different to what I see or saw three times a week, up there. Completely different’. [93, p.7]

In addition to mobile dialysis units, there are calls for more options to receive care ‘on Country’. Studies suggest that this is supported by both patients and staff [86, 117]. Home haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis could provide another option for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, however there are currently barriers such as the quality and availability of housing, health hardware, health literacy, and access to local medical support [116]. While a number of patients have expressed interest in home dialysis, some also worry that without nurses to assist, this option would place a burden on their family members.

MBS items to assist people living in remote areas to receive dialysis close to home

In November 2018, The Federal Government introduced a new MBS item to provide funding for the delivery of dialysis by nurses, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners and Aboriginal Health Workers in a primary care setting in remote areas [92]. Item 13105 pays for the supervision of dialysis in very remote areas of Australia defined as Modified Monash Model 7.

Workforce

The benefits of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce in improving Indigenous kidney care in Australia are increasingly being recognised. An important aspect of improving primary, secondary and tertiary care has been the inclusion of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce. The Aboriginal Health Worker role began in the 1950s [120], and this role has evolved and expanded over time, particularly in the primary care sector, in both community controlled and mainstream services. The role of Aboriginal Liaison Officers in hospitals around Australia has evolved to helping improve access and quality of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, to act as a cultural broker, and assist patients and family members to better understand and make more informed decisions about their health care options [121]. In 2009, the Federal Government recognised the importance of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce as part of the Closing the Gap initiative [122].

There has also been increasing emphasis on the role of non-Indigenous staff and services in improving care, with recognition of the need to address gaps at interpersonal, service and systems level. This has led to an increase cultural safety and competency training for staff, and a move toward addressing intuitional and systemic racism [55]. Within the workforce, there are also ongoing challenges in maintaining a well-developed and skilled workforce. In particular, recruitment and retention and high turn-over of staff is a challenge in remote areas [123].

Patient perspective

There have been repeated calls by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander renal patients for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce to be strengthened [117] and for the non-Indigenous workforce to be more culturally aware. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people seeking health care, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff can help create a feeling of belonging and acceptance, which increase comfort, and can influence outcomes of care [124]:

‘…oh the people, the facilities, and you just have that rapport with people there and they make you feel welcome so you tend to go back … rather than just sitting in a mainstream hospital or a little surgery where you’re the only little black face … it’s much better going to your own mob…’. [124, p.8]

In addition, Aboriginal patient-experts have discussed the need for better cultural training for non-Indigenous staff [125]. One project acted on this feedback from a patient-expert group and co-designed with patient-experts (co-researchers) a training program for nurses in regional and remote renal clinics, including Purple House nurses. The co-researchers conducted the workshops with the nurses and after each workshop would evaluate and improve the program. Reflections from the Aboriginal co-researchers was positive, and the nurse participants reported that the workshops were useful and helped them better understand their patients. One participant remarked:

‘The biggest thing I have learnt is to look at my patients as people not patients. Listening to their stories [in Workshop 3] just changed everything for me. They’re more than just patients on dialysis. There is more to them, there is so much more. And I think that I never stopped and thought about that [before]’. [125, p.33]

Communication and approaches to care

Over the past 20 years there has been significant focus on staff-patient communication and relationship challenges and barriers between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and non-Indigenous staff [81], and how these continue to be a major component in determining the quality of care and subsequent outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Some healthcare staff, specifically non-Indigenous staff, struggle with speaking effectively with their patients [86, 126]. One study showed that one third of clients had trouble understanding their doctor [127], which was further complicated for Indigenous patients if English was their third or fourth language.

‘I – we would like to be spoken to clearly in an understandable way by doctors –…by doctors who like Anangu (Aboriginal people), by understanding [empathetic] doctors who talk – they’re good – a lot of other doctors can’t talk with us… their talk is hard [to understand]’. [126, p.8]

Patients have described poor communication with staff about their kidney condition with one study showing that this left patients ill-informed about their options for treatment [126]. This impacted on ‘compliance’ with care and also patient decision-making. One qualitative study showed that patients are often not spoken to about transplant as an option. Aboriginal renal patients and healthcare providers have both expressed their desire for more positive relationships but structural barriers within the current healthcare system exist [128]. Nurses and health service staff are often busy and unable to take the time needed to build strong relationships, and cultural education training is often not compulsory, targeted appropriately or prioritised due to lack of resourcing. At times basic cultural awareness or competency training has been provided, focused on ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture’, has been provided, but has left some staff unsure and confused about the specifics of how best to care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, leading to further misunderstanding [93]. The complex history of colonisation and racism in Australia has created barriers and a lack of trust between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and their healthcare workers and services [129]. Cultural safety and similar approaches that take into account history, power and ongoing colonisation and racism impacts are more effective [130].

A shift in focus from the cultural awareness of individual practitioners to changing health services with the responsibility of ‘incorporating cultural values into the design, delivery and evaluation of services’ is also required [108]. In 2011, the National Health Ministers endorsed ten National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) standards [131]. One of these was partnering with consumers with an emphasis on consumer engagement in the design, delivery and evaluation of health care services and systems, and that patients and clients can increasingly be partners in their own care. In 2017, six specific actions for improving care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were added [132], the first of which was working in partnership and building effective and ongoing relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, communities, organisations and groups.

Health knowledge for patients is strongly linked to communication with health care staff. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander renal patients have described not being informed about their disease [133]. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients it is important that the family is included in health knowledge to help with management. Without adequate knowledge of their own illnesses it is difficult for patients to management their illness effectively [93].

Some programs have been shown to improve staff-patient relations and communication. For example, the SA Health Mobile Dialysis Bus evaluation revealed improved relationships and understanding between staff and patients [93]:

‘you get to know the patients and they have a bit more of a trust and share a lot more. So you become a lot more aware of what’s important to them, and the cultural significance of returning home and getting a connection with Country … and family’

‘They also would listen to you more about their health, because we had gained a different rapport, a different relationship and perhaps a bit more trust.’

‘they (the staff) are a lot more happier to look after the Indigenous patients because they think that they understand a little bit more every time they do it.’ [93, p.8]

Peer support

There is increasing recognition of the unique peer support role that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with lived experience of kidney disease, dialysis care and transplantation can provide for other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people new to kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation and workup. These emerging roles are defined and named differently across Australia. In the NT, Purple House supports Patient Preceptors whose role is to provide expert advice and reassurance to patients as part of the professional health service team [134]. They have conducted The Panuku Renal Patient Preceptors Workforce Development Project and in 2019 produced a report outlining this role, how it developed and where this role fits in relation to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce roles.

In 2017, Dr Jaqui Hughes, Indigenous nephrologist, initiated an Indigenous Patient Voices: Gathering Perspectives Finding Solutions for Chronic and End Stage Kidney Disease Symposium in which the priorities of health care users, expert-patients and carers, and opinions of non-patient-carer delegates were documented and used to provide a rationale for health care reforms [81]. Key solutions were identified with specific details presented as a call for action. These included:

- increased local and Indigenous workforce, including patient-expert navigators

- improved access to culturally safe renal care close to home

- meaningful health information, promotion and education in relation to chronic diseases, renal care, transplantation and how health systems operate

- strengthened partnership with primary health care and Indigenous organisations

- new models of care that are responsive to Indigenous people’s needs, i.e. separate gender spaces in dialysis

- an appropriately culturally competent and clinically safe, skilled and knowledgeable interprofessional workforce who can communicate clearly and respectfully

- increased Indigenous leadership, governance and self-determination.

Similar findings arose from studies conducted in the NT and nationally over the previous 20 years [135, 136].

Strategies to improve kidney care in Australia for and with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Over the last five years, the focus within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kidney care in Australia has been increasingly to:

- Establish and support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient-clinician partnerships, peers support and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance within health care, policy development and research with:

- six new Indigenous quality and safety standards that promote working in partnership and improving cultural safety in health care [132]

- Indigenous patients invited, welcomed and sponsored to attend and present at renal and transplantation conferences [137]

- Indigenous reference groups and advisory groups increasingly involved in decision making in research, data systems (ANZDATA), clinical guideline development and clinical care [56]

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient experts providing peer support for other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, in volunteer, research and paid roles (patient navigator and preceptor models) [134]

- community consultations with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, carers, family members and communities [59].

- Actively address, fund and respond to gaps in care identified in studies, policy briefs and consultations by:

- increased funding for haemodialysis closer to home for people in remote locations through changes to MBS items [92]

- improved information, access and support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians needing kidney transplantation through the National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT), increased outreach services, coordination and support roles [138]

- increased support and survival post-transplantation [138]

- identifying ways to improve cultural awareness and cultural safety of health professionals and services, and address systemic racism and bias [132, 139]

- Patient journey mapping to identify the lived experience and the challenges encountered by patients when accessing the health system and by healthcare professionals as they strive to provide clinically and culturally responsive care [140, 141]

- increased responsiveness of health professionals and kidney care services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient needs, with new models of practice and models of care and increased use of telehealth [57].

- Recognise the importance and needs of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce in renal care, and the unique positioning of Aboriginal health professionals, peer navigators, preceptors and coordinators [142].

- Work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations to identify effective ways to prevent or slow the progression of kidney disease [57, 59].

Timeline of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kidney care

In order to make sense of what has been occurring in the last five years it can be helpful to look back over earlier initiatives to improve kidney care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This timeline (Table 11) is not exhaustive of all activities that have occurred across Australia but is intended to provide an overview of activities and trends.

In the 1980s there was a focus on improving access to dialysis care in remote and regional areas such as Darwin [134], Tiwi Islands [143, 144], the Kimberly region [118], Western Desert [145] and Thursday Island [146]. This occurred and continues to occur in a range of sites across Australia – in 2019, the first dialysis centre in the APY Lands in SA was opened [147]. There has also been a focus on providing mobile dialysis services via dialysis bus or truck, particularly in Central Australia [119], the Kimberly area [118], and across SA [93]. Such initiatives have been supported by a mixture of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations and Government health services.

Increasing access to transplantation is another major focus, with the IMPAKT study beginning in 2004 [148, 149] and the establishment of the National Indigenous Kidney Transplant Taskforce in 2019 [137], and the equity and access sponsorships [138]. Alongside these clinical changes and priorities, a number of specific research projects have also been conducted. These have focused on feasibility studies for dialysis in rural and remote locations [143, 144], improving communication and shared understanding [136], identifying barriers and enablers to care [110, 140], and better understanding the experience and progression of CKD for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [150].

Over the last eight years there has also been a continuing and increasing focus on Indigenous Voices [81] and Indigenous Governance [57], patient experts, peer support and working in partnership. Activities and projects have established or investigated options for community engagement and peer support, including establishing programs involving patient navigators to support new dialysis patients [134] and patient experts teaching dialysis staff about cultural awareness [151]. Increasingly strategies are in place to ensure that polices, practice, models of care and new guidelines are informed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s lived experience of renal disease and renal care [56].

Timeline abbreviations

CC Community Consultations

ClinG Clinical Guidelines

ClinExp Clinical Expertise

HD Haemodialysis

IndG Indigenous Governance

IndWf Indigenous Workforce

KidT Kidney Transplantation

Policy Policy

Pt Adv Patient Advisory Activities

R-HD Remote Haemodialysis

Res Research

Addressing systemic racism

There is an increasing body of work describing the importance of addressing institutional and systemic racism in the health system in Australia in order to achieve health equity. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-2023 includes a vision for the Australian health system to be – free of racism and inequality and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have access to health services that are effective, high quality, appropriate and affordable [164]. Past initiatives addressing racism have focused on individual experiences of racism rather than the structural mechanisms that contribute to inequity in the health system [165]. This focus is changing, for example, a framework has been developed in Australia to measure institutional racism in Australia’s health care system using publicly available data [166]. The framework has been tested in Queensland and is in the process of adaptation for other states [165].