Giles L, Bauer L (2019)

Central Coast Local Health District

Corresponding author: Luke Giles, Health Promotion Service, Central Coast Local Health District, Gosford, NSW, 2250, ph: (02) 4320 9709, email: luke.giles@health.nsw.gov.au

Suggested citation: Giles L, Bauer L (2019) Working towards a tobacco-free Aboriginal community through an arts-based intervention. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 19(4) Retrieved [access date] from https://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/working-towards-a-tobacco-free-aboriginal-community-through-an-arts-based-intervention

Abstract

Objective

Higher than average smoking rates are observed in Aboriginal populations. This project used a creative art approach and aimed to:

- Raise the profile of smoking as an issue within the Aboriginal community;

- Contribute towards changed social norms about smoking; and

- Engage with the Aboriginal community and organisations on ways to address smoking.

Methods

An art competition was held with the Central Coast Aboriginal community to create artworks around the theme of smoking.

To facilitate the production of artworks, Central Coast Local Health District Health Promotion Service engaged an Aboriginal artist to lead art workshops with local Aboriginal organisations. Art resources were provided at the workshops. Aboriginal organisations were encouraged to have their staff, clients and community members participate in the workshops.

The community voted for their favourite artworks online. Prizes were awarded to the artworks that received the most votes.

Results

Ten local Aboriginal organisations were invited to host a workshop, and 5 participated. Seven art workshops were delivered, with 66 people attending the workshops and 38 artworks being produced. Eighteen artworks were entered into the art competition, which attracted 156 votes from the community.

Conclusions

The art workshops and competition were effective ways to engage the Aboriginal community on the topic of smoking cessation. Additional work is planned to build upon the momentum established by this project, such as using the artworks developed from the workshops in Aboriginal-specific resources and campaigns to contribute towards decreased smoking rates in the Aboriginal community.

Implications

Aboriginal communities can be engaged on health issues such as smoking through culturally-appropriate interventions such as art.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nicole Kajons (implementation support), Samantha Batchelor (manuscript writing and editing support), Kylie Cassidy (artistic guidance and support at workshops), and participating Central Coast Aboriginal organisations and the Central Coast Aboriginal community (participation in art workshops and competition).

Download PDF (430KB)

Introduction

Smoking in Aboriginal communities is a significant health issue, and higher than average smoking rates are observed in Aboriginal populations. The Aboriginal adult smoking rate in 2017 was 28.5% across NSW, almost double the non-Aboriginal population smoking rate of 14.7%.1 Smoking causes 12% of the disease burden experienced by Aboriginal populations, contributing the highest proportion of harm to Aboriginal health of any modifiable risk factor.2

Art is an important component of Aboriginal culture.3 Creative arts-based health promotion projects have been used in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations across Australia to address a variety of health issues, including smoking.3-10 A number of artistic mediums have been utilised in Indigenous arts-based health promotion work, including painting, dance, and music. When using an arts-based approach, projects and resources must be culturally appropriate in order to appeal to Aboriginal populations.3-4 It is recognised that while arts-based projects can be valuable for engaging the Indigenous community, evaluation is complex and determining the effectiveness of projects in changing behaviour is difficult.5, 9 Two similar Aboriginal-targeted arts-based smoking themed projects were identified from the literature, both of which followed a similar structure to this project.4-5

Central Coast Local Health District (CCLHD) Health Promotion Service (HPS) used a creative art approach to address smoking in the local Aboriginal community. The objectives of this project were to:

- Raise the profile of smoking as an issue within the Aboriginal community;

- Contribute towards changed social norms about smoking; and

- Engage with the Aboriginal community and organisations on ways to address smoking.

Methods

The local Aboriginal community was identified as a key population group for CCLHD HPS to target with a smoking cessation intervention as a result of the high smoking rates that are observed in Aboriginal populations. An arts-based intervention approach was proposed by CCLHD HPS. Key stakeholders within the Aboriginal community were consulted to determine the appropriateness of the proposed intervention. Feedback from these stakeholders was considered in finalising the design of the intervention.

The intervention consisted of art workshops and an art competition with a smoking cessation theme. Members of the Aboriginal community were encouraged to create artworks highlighting the issue of smoking, its impact on the Aboriginal community, and ways that smoking can be addressed by the Aboriginal community. Artworks could be entered into a competition, with the community voting for their favourite artworks online. Workshops were conducted in May and June 2018.

To facilitate the production of artworks, CCLHD HPS engaged a local Aboriginal artist to lead art workshops hosted at local Aboriginal organisations. The artist provided artistic guidance and support to workshop participants. Art resources such as paints, brushes and canvases were provided at the workshops.

Workshops were delivered in partnership with Aboriginal organisations. Organisations provided a space for the workshop to be held, and promoted the workshop to staff, clients and community members who have contact with their service.

To commence the art workshops, 6 short open-ended questions were asked of the workshop group collectively. The purpose of these questions was to encourage workshop participants to think critically about smoking, and to consult with members of the Aboriginal community on ways that smoking could be addressed. The questions included:

- How is smoking viewed in the Aboriginal community?

- What impact does smoking have on the Aboriginal community (especially pregnant Aboriginal women and Aboriginal youth)?

- How would the Aboriginal community benefit from lower smoking rates?

- What might make it hard for Aboriginal people to quit smoking?

- What do you think would help Aboriginal smokers to quit?

- What do you think would help Aboriginal people to not start smoking?

Responses to these discussion questions were recorded non-verbatim by administration staff from CCLHD HPS.

For further guidance, workshop participants were encouraged to create an artwork around the following themes and/or groups:

- Themes

- How badly smoking affects our community

- The benefits of a smoke free environment

- How we can address smoking in our community

- How quitting smoking can be supported by the community.

- Groups

- The whole Aboriginal community

- Pregnant women

- Youth

Once artworks were produced at the workshops, artists had the option of entering their artwork into the art competition. Artworks were collected by CCLHD HPS, and artists completed an art competition entry form. The entry form included artist and artwork details, as well as questions relating to the inspiration for the artwork and an opportunity for the artist to share a story related to smoking (either their own smoking or that of someone around them). Artworks could be returned to artists at the conclusion of the art competition at the artist’s request. A structured mixed methods workshop evaluation was also completed by participants.

Voting for the art competition was administered via Survey Monkey. All artworks that were entered in the competition were listed on the voting page with an image of the artwork, the name of the artist and the title of the artwork. The voting page was set so that each device could only submit one vote. The voting link was circulated to all artists who submitted an entry to the art competition, all local Aboriginal organisations, an Aboriginal interagency network, as well as other community and arts venues. Competition voting was open for a period of 3.5 weeks, from 18 June – 12 July 2018.

Artworks that were entered in the competition were displayed at two local events – a NAIDOC Community Day, and 5 Lands Walk, a cultural community event. Attendees at these events were encouraged to vote for their favourite artworks using the web link. A project team member was present at one of these events to enter votes from community members.

Prizes were awarded for the art competition entries which received the most votes, in the form of Visa gift cards – $500 for first place, $250 for second place, and $125 for third place. A ‘young artist’ prize of $250 was also awarded for the artwork created by an artist under 25 years of age that received the most votes.

Results

Five of the 10 local Aboriginal organisations that were targeted for the project participated. Seven art workshops were delivered; 1 at each participating organisation except for the local Aboriginal Medical Service which hosted 3 workshops. Workshops typically lasted 2-3 hours. Sixty-six people attended the workshops. It is unclear how many of these people identified as Aboriginal, as participation was open to all people who engage with the participating Aboriginal organisations. Thirty-eight artworks were produced, and 18 artworks were entered in the art competition which attracted 156 votes from the community.

A wide range of responses were provided to the qualitative discussion questions asked of workshop participants at the beginning of the workshop (Table 1).

Art workshop evaluations were completed by 22 participants and showed that 100% of participants rated the art workshop as ‘good’ or ‘excellent’, and 100% either agreed or strongly agreed that the workshop met their expectations. All participants also agreed or strongly agreed that the art workshop was well organised, and 81% indicated that the workshop was well advertised and communicated.

Thirty-two per cent of participants who completed the art workshop evaluation reported that they were a current smoker, and 71% of these people would like to quit smoking within the next 6 months. Fifty per cent of respondents indicated that they would seek smoking cessation support from an Aboriginal Medical Service if they were interested in quitting, and 32% would seek support from the Quitline, a smoking cessation telephone support service. This data could inform how smoking cessation support is provided in the Aboriginal community.

Further to these results from the art workshops, entrants to the art competition were asked to share the inspiration behind their artwork:

“My mother’s family have all suffered from heart disease. My artwork represents my mother and aunties in the community who have battled heart disease mostly caused by smoking and the effects it has had on their souls.”

“I am currently 39 weeks pregnant. I grew up with parents that smoke. My painting illustrates that smoking may change the perception or portray that smoking is acceptable. As adults, we are the role models.”

Additionally, artists were able to share a story about either their own smoking or that of someone close to them:

“So many of my family members have smoked and died young. My dad has one kidney and one lung from cancer. It is never too late to give up and kick those cancer cells. He is still here to tell his story aged 71 and quit smoking at diagnosis.”

“My story is work related and being able to provide Nicotine Replacement Therapy to clients to help them reduce or quit smoking. When a pregnant woman is able to stop smoking from your support it is a great feeling.”

These quotes provide insight to the impact and experiences of Aboriginal people in regards to smoking.

Table 1: Summary of responses from workshop participants to group discussion questions asked at the beginning of art workshops

| How is smoking viewed in the Aboriginal community? |

|---|

| · It is used to relieve stress, anxiety and worry of daily life |

| · Seen as a coping mechanism |

| · A way to wind down |

| · It’s my only vice, but it’s a biggie |

| · Can be seen as normal |

| · More acceptable than other drugs |

| · Social activity |

| · Can lead to isolation |

| · A lot of people against it |

| · Harder to smoke, fewer places to smoke |

| · Seen as a bad thing |

| · Feel bad about it, not in control |

| · Shame |

| · Guilt with smoking – elders find it disrespectful |

| · Young ones don’t like it |

| · It stinks |

| · Expensive habit |

| · Anger, especially at the fact cigarettes were historically given as a wage part payment |

| What impact does smoking have on the Aboriginal community (especially pregnant Aboriginal women and Aboriginal youth)? |

| · Some Aboriginal women stop smoking while pregnant, but start again after pregnancy to help with stress and anxiety |

| · Divisive in social situations |

| · Financial – expensive habit |

| · Budgetary – needs of the family versus purchasing smokes |

| · Causes anger and fights within families when there is no money left to buy cigarettes |

| · A bad influence on children and families |

| · Young people copy smoking behaviour |

| · Peer pressure by friends |

| · Impacts health of smoker and of others e.g. kids |

| · Early loss (death) of loved ones |

| · History repeating itself with the children starting to smoke |

| · Generations of addicted people |

| How would the Aboriginal community benefit from lower smoking rates? |

| · Improved health |

| · Longer lives, less deaths |

| · Elders and grandparents around longer |

| · Less chronic disease like lung and peripheral vascular diseases |

| · Save money – more money in your pocket |

| · Less tax |

| · Public expenditure on health would drop |

| · Cleaner air to breath |

| · Reduce passive smoking |

| · Less passive smoke for kids |

| · Less rubbish on the ground – cigarette butts don’t break down |

| · Fire prevention by fewer butts being thrown away that can start fires |

| · ‘Closing the gap’ outcomes improved with lower smoking rates – smoking is responsible for 12% of the health gap causes |

| What might make it hard for Aboriginal people to quit smoking? |

| · Smoking is an addictive habit |

| · Habit, routine, withdrawals, social pressure, stress |

| · Withdrawal symptoms, nicotine cravings |

| · Smoking is used for coping and relaxation |

| · Stress, worry, anxiety |

| · Smoking is used for stress relief, dealing with family crisis, provides an escape – there is a need to find an alternative treatment for this stress release |

| · Other addictions- such as alcohol |

| · A young initiation age when beginning to smoke cigarettes |

| · Enjoyment – from rolling own cigarettes |

| · Having other smokers around – in the community or living with you |

| · Smoking is a part of social activity for some people |

| · Cost of patches |

| What do you think would help Aboriginal smokers to quit? |

| · Need more anti-smoking/quit classes in community centres |

| · Video of Aboriginal people with smoking related diseases |

| · TV ads are effective, they make you think about the consequences |

| · Pictures on the cigarette packets |

| · Finding a stress release alternative |

| · Having something else to do you’re your hands |

| · Showing financial impact of smoking |

| · Monetary incentive |

| · Apps (e.g. Quit Now) |

| · Social support and positive encouragement rather than shaming |

| · Support group |

| · Cold turkey quitting |

| · Breaking the addiction of nicotine |

| · Nicotine Replacement Therapy |

| What do you think would help Aboriginal people to not start smoking? |

| · Set a goal to not start smoking |

| · Communicate the financial benefit of not smoking – how much it will cost as a daily, weekly, monthly, yearly, lifetime cost |

| · Monetary incentives |

| · Avoid smokers |

| · Avoid peer pressure |

| · Coping strategies to combat peer pressure |

| · Awareness |

| · Education at school |

| · Knowing about side effects |

| · Seeing health impacts of others who smoke |

| · Not selling to underage people |

| · Community education, outreach services |

| · Creative programs, other things to do |

Discussion

The art competition provided a new and culturally appropriate way to engage the local Aboriginal community on the issue of smoking. Useful data and insights were received from the workshop participants from the discussion at the start of the workshops, the workshop evaluation forms, and the art competition entry forms.

A number of high quality and engaging artworks were produced by workshop participants. These artworks will be used in future smoking cessation work delivered with the Aboriginal community by CCLHD HPS. The winning artwork is being featured in a social marketing campaign currently in development, on an incentive shirt for participants in the local Aboriginal Medical Service’s smoking cessation clinic, and on a decal design for nicotine replacement therapy vending machines located in CCLHD’s major public hospitals.

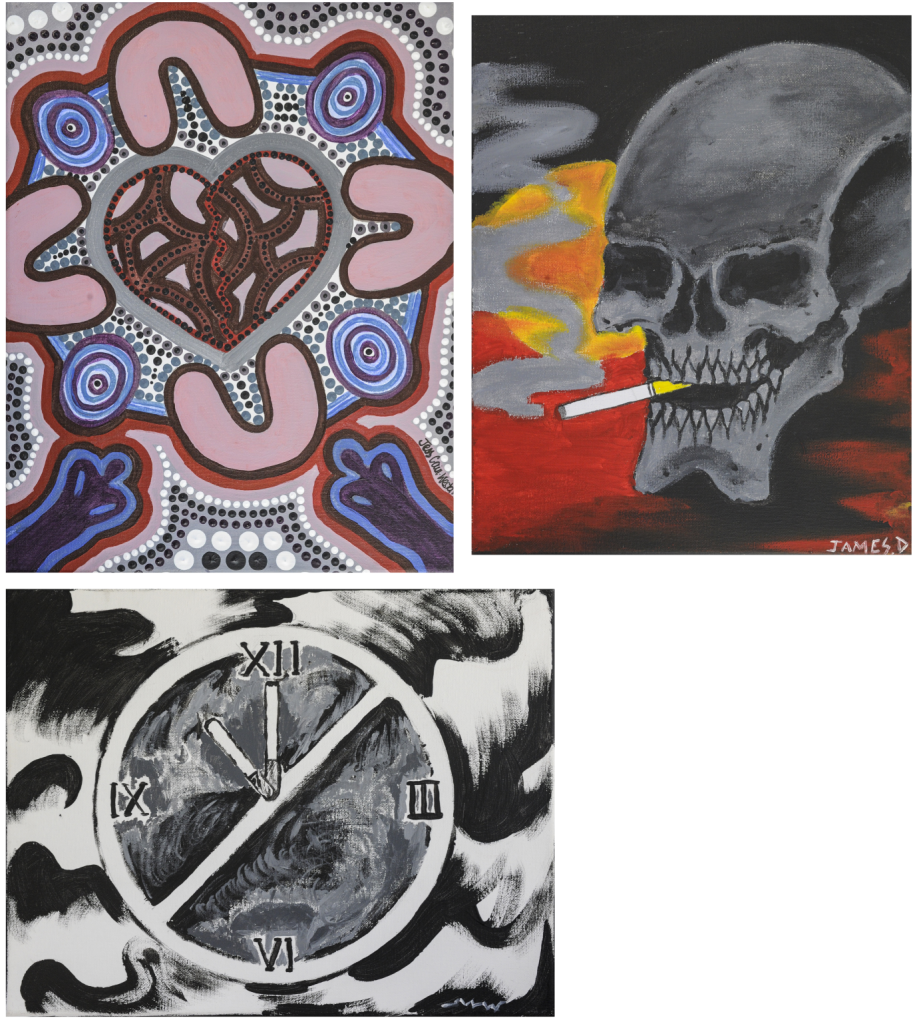

An important consideration of smoking cessation work within the Aboriginal community is the social acceptability of smoking, and the need to reduce possible social and cultural exclusion felt by people who quit smoking.11 Themes of social connection around smoking and its health impacts were reflected in the winning artwork, with symbols representing family gathered around a diseased heart reflecting the prevalence of heart disease within the artist’s family, and grey dots representing smoke connecting the family members (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Collage of winning artworks. Top left: 1st place – ‘Heart ‘n’ Soul’, Jess Cain-Westaway, acrylic on canvas; top right: 2nd place – ‘Choo Choo Death’, James Daldorf, acrylic on canvas; bottom left: 3rd place – ‘Time to Quit’, Mark Watt, acrylic on canvas.

A limitation to the project was that practical smoking cessation support was not provided as part of the project. While the art workshops provided an opportunity to raise the issue of smoking within the Aboriginal community, further work will be required to effect change to smoking rates.

Unfortunately, only half of the local Aboriginal organisations participated in the project by hosting an art workshop. Reasons for non-participation included competing organisational priorities, lack of time, and no response being received from organisations despite repeated follow up.

Other similar art projects have conducted a framework analysis of artwork content and themes4-5, though this type of analysis was outside the scope of this project.

This project was also intended to be strategic in that it sought to establish partnerships with Aboriginal organisations. The art workshops were partly used as a way to establish relationships with local Aboriginal organisations, with a view to additional smoking cessation projects being delivered in partnership with these organisations. To date, one organisation has accepted the offer from CCLHD HPS to provide additional support in regards to smoking cessation, while another two organisations have smoking cessation work either completed or ongoing. Opportunities to engage other Aboriginal organisations that did not participate in the art project are being explored. Consideration is also required in regards to reaching Aboriginal people who do not engage with the 10 local Aboriginal organisations – this may be achieved through implementing an Aboriginal-targeted social marketing campaign and other population-wide tobacco control initiatives.

Conclusion

The art workshops and competition were effective ways to engage the local Aboriginal community on the topic of smoking cessation. Additional work is planned to build upon the momentum established by this project, such as using the artworks developed from the workshops in Aboriginal-specific resources and campaigns, and delivering tailored projects with individual Aboriginal organisations, to contribute towards decreased smoking rates in the Aboriginal community.

References

- NSW Ministry of Health. HealthStats NSW. Current smoking in adults by Aboriginality, trends [Internet]. North Sydney, NSW Ministry of Health; 21 May 2018 [cited 27 July 2018]. Available from: healthstats.nsw.gov.au/Indicator/beh_smo_age/beh_smo_atsi_trend

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study – Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011 [Internet]. 2016 [cited 15 October 2018]; Australian Burden of Disease Study series no. 6. Cat. no. BOD 7. Canberra: AIHW. Available from: aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/illness-death-indigenous-australians/contents/table-of-contents

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Institute of Family Studies. Supporting healthy communities through arts programs [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; Cat. no. IHW 115. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/142afee1-f0b5-40c9-99b5-5198feb255a4/ctgc-rs28.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- Gould G, Stevenson L, Oliva D, Keen J, Dimer L, Gruppetta M. “Building strength in coming together”: a mixed methods study using the arts to explore smoking with staff working in Indigenous tobacco control. Health Promot J Austral [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; 29(3):293-303. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.178

- Gould G, Skeel M, Gruppetta M. Exploring anti-tobacco messages from an experiential arts activity with Aboriginal youth in an Australian high school setting. J App Arts & Hlth [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; 8(1):25-37. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah.8.1.25_1

- Guerin P, Guerin B, Tedmanson D, Clark Y. How can country, spirituality, music and arts contribute to Indigenous mental health and wellbeing? Australas Psychiatry [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; 19(suppl 1):S38-41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/10398562.2011.583065

- Gill J. The Lung Story. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker J [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; 23(1):7-8. Available from: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=198496450026770;res=IELIND

- McEwan A, Crouch A, Robertson H, Fagan P. The Torres Indigenous Hip Hop Project – evaluating the use of performing arts as a medium for sexual health promotion. Health Promot J Austr [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; 24(2):132-136. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1071/HE12924

- Parsons J, Boydell K. Arts-based research and knowledge translation: some key concerns for health care professionals. J Interprof Care [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; 26(3):170-172. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2011.647128

- Ivers R. A review of tobacco interventions for Indigenous Australians. Aust N Z J Public Health [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2018 Nov 1]; 27(3):294-299. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00398.x

- Twyman L, Bonevski B, Paul C, Bryant J. Perceived barriers to smoking cessation in selected vulnerable groups: a systematic review of the qualitative and quantitative literature. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Nov 21]; 4:1-15. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006414